After Scott Pruitt resigned from the Environmental Protection Agency this summer, many in the media—this reporter included—wondered whether Ryan Zinke might be the next to go. The Interior secretary was facing more than a dozen investigations over allegedly unethical and wasteful behavior at the agency.

Zinke’s fate, however, ultimately depended on the results of those investigations. So it many were alarmed when The Hill reported on Tuesday that Zinke was getting rid of the person in charge of several of those inquiries—and would replace her with a Trump political appointee with no experience in government oversight.

The Hill’s information seemed pretty solid. It came from an email “Fond Farewell” and

sent by Ben Carson, the secretary of Housing and Urban Development, to agency staff. “It is with mixed emotions that I announce that Suzanne Israel Tufts, our Assistant Secretary for Administration, has decided to leave HUD to become the Acting Inspector General at the Department of Interior,” Carson wrote. Though not explicit, this implied that Mary Kendall, who has served as the Interior Department’s acting inspector general for nearly a decade, would be fired or demoted.

The Washington Post, Outside magazine, and others soon picked up the news.

This is a very big deal. Politicizing the oversight function is dangerous, especially in the absence of any Congressional oversight. Changing IGs in the midst of multiple serious investigations of the agency's head should raise alarm bells everywhere. https://t.co/G8YvcRfX91

— Michael R. Bromwich (@mrbromwich) October 16, 2018RM @RepRaulGrijalva, @RepMcEachin, @RepDonBeyer & @RepHuffman are urging scrutiny of the new @Interior Inspector General. It's deeply concerning that as IG this Trump appointee could interfere with the multiple Zinke Investigations currently underway. https://t.co/D2jQcFmjz3 pic.twitter.com/czpVYCggjV

— Nat Resources Dems (@NRDems) October 18, 2018On Thursday evening, though, the story changed drastically. Heather Swift, the head spokesperson at Interior, denied in an email to BuzzFeed’s Zahra Hirji that Zinke ever planned to replace Kendall with Tufts, and accused Carson of sending an “an email that had false information in it.”

“This is a classic example of the media’s jumping to conclusions and reporting before facts are known,” Swift wrote, adding that Kendall is still in charge of the Inspector General’s office at Interior. Contradicting Carson’s email, Swift said Tufts was merely considered “as a potential candidate for a position” in the Inspector General’s office, not offered the top job.

I want to reiterate how bizarre and messy this is. The top @Interior spokesperson just accused @HUDgov (and really @SecretaryCarson) of sending out an email "that had false information" https://t.co/sZOnk56hn9

— Zahra Hirji (@Zhirji28) October 18, 2018Swift’s attempt at a clarification has not quieted the outrage. “This administration can’t stop embarrassing itself or keep its story straight for five minutes,” Arizona Rep. Raúl Grijalva, the top Democrat on the House Natural Resources Committee, told Politico. “Nobody is buying this explanation and we’re not going to stop pressing for answers.”

What this latest scandal has done, however, is shine a much-needed light on the messy state of agency Inspector General offices—particularly the Interior Department’s. These offices, as the Project On Government Oversight (POGO) notes, “serve as crucial independent watchdogs within federal agencies, and are indispensable to making our government effective and accountable. These watchdogs investigate agency mismanagement, waste, fraud, and abuse, and provide recommendations to improve federal programs and the work of federal agencies.”

Like Supreme Court nominees, Inspectors General are supposed to be nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. This process ensures a critical, public vetting under oath—and it ensures that the watchdog can’t be fired by the head of the agency they’ve been tasked with investigating. Swift noted this in her clarification email to BuzzFeed, saying Zinke couldn’t have fired Kendall because “only the White House is able to reassign senate confirmed officials.”

But Kendall was not confirmed by the Senate. Though she has been leading Interior’s office since 2009, she has been serving only in an “acting” capacity. In other words, the Interior Department has not had a confirmed inspector general for almost a decade. If it had, there never would have been a question about whether Zinke fired her, because he wouldn’t have had that power. “This story wouldn’t have been a story had there been a permanent IG in that office,” said Elizabeth Hempowicz, the POGO’s public policy director.

The Interior Department’s current inspector general vacancy is the longest-ever vacancy for that position. But it’s not the only one. Fourteen other agencies—including the EPA, the CIA, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Defense—don’t have Senate-confirmed inspectors general. That’s not a problem limited to the Trump administration, as many vacancies date back to the Obama administration. And as Hempowicz told me, “Congress hasn’t moved as quickly as they can on some nominations.”

Whatever the truth of Zinke’s latest kerfuffle, Hempowicz sees one silver lining. “I was surprised at the enormity of the response to this story,” she said. It may have been just the brazenness of putting a political appointee in charge of independent oversight. But it also could mean that “people have a real appetite to know that government is working the way it’s supposed to work,” she said.

Just hours after we spoke, with very curious timing, news broke that the Interior Department’s inspector general had concluded that Zinke broke department rules by spending thousands of taxpayer dollars on travel with his wife. The “new report says Zinke sought to designate his wife an agency volunteer in order to obtain free travel for her, that he often brought her in federal vehicles in violation of agency policy and that he neglected to get permission from ethics officials when he took campaign donors on a boat trip,” according to Politico.

It seems that Kendall is still in charge of oversight at Interior, and that Zinke still might be the next cabinet member to lose his job over a travel scandal.

On August 24, the tenants of two buildings near the Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Los Angeles received letters from their landlord notifying them of a rent increase of over $800 a month. The increase was not a result of repairs or tax increases but rather, the letter said, of the upcoming election in November.

The section of the ballot in question is Proposition 10, which, if it passes, would repeal a 1995 state law prohibiting local governments from enacting rent control on apartments and homes built after that year (or even earlier in cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco). According to the letter: “Although you don’t want higher rent and we did not plan on charging you higher rent, we may lose our ability to raise rents in the future. ... Therefore, in preparation for the passage of this ballot initiative we must pass along a rent increase today.” If the ballot initiative failed, however, the landlord, Rampart Property Management, promised to “revisit the rent increase with a desire to cancel it.”

For Maria (who prefers not to use her real name out of fear of retaliation by her landlord), waiting to find out was too big a risk. An immigrant from Guatemala, she pays $600 a month to share a bedroom with her 11-year-old son in a two-bedroom apartment—another family lives in the second bedroom, with a fifth tenant taking the living room. A couple hundred dollars extra in rent would not be feasible for Maria, who lives off welfare after losing her job last year. A month later, Maria received a second letter billed as an “olive branch”—a reduction of the increase to $238 a month. When Maria and several other tenants went to the property manager to ask for an explanation, he told them that so many tenants had threatened to leave that the landlord had no choice but to lower the proposed rent hike.

As the vote on rent control approaches, tenants across California have been harassed, served with eviction notices, and forced to pay more rent. In Concord, an entire building of 29 families was given 60-day eviction notices, with landlords explicitly citing Proposition 10 as the cause. In Modesto, tenants of a single-family building were not only notified of a rent increase, but also encouraged to vote against Prop 10, which the landlord said would “eliminat[e] the current availability of single family homes to rent.” Shanti Singh of the California renters’ rights organization Tenants Together says these are not isolated incidents: “This is punishing renters for participating in the democratic process. And we’re expecting to see a lot more of this in the coming month.”

These efforts are part of a massive attack corporate landlords have been waging on rent control across the state. And though they claim to be speaking for the mom-and-pop landlords of California, the leaders of this campaign are some of the largest property owners in the country. Blackstone, the world’s largest real estate management firm, has spent nearly $7 million to defeat Prop 10. Other top donors include Equity Residential, the third-largest apartment owner in the country, and AvalonBay Communities, the twelfth-largest property owner. These mostly Wall Street–based moguls have pooled as much as $60 million (with as much as $2 million raised in the last week alone) primarily to fund an enormous advertising blitz, eclipsing the $22 million raised by the coalition of over 150 housing advocacy, community, political, and faith-based organizations that, along with the California Democratic Party, has rallied around the ballot initiative.

If Proposition 10 passes, it would be not only the most significant attempt to roll back state limitations on rent control, but also the greatest success to date of the burgeoning national tenants’ rights movement—and real estate groups are responding with full force. Rent control, which is illegal in 27 states, has become a campaign issue across the country, and the landlord lobby has been rushing to squelch tenants’ rights campaigns wherever they spring up.

In Boston, a bill far more modest than Prop 10—it was intended merely to track evictions and give the city a way to notify evicted tenants of their rights—was killed in the state legislature this past May after landlord groups put pressure on lawmakers. In Oregon, the landlord lobby has already launched a multimillion dollar super PAC, More Housing Now!, to oppose an anticipated Prop 10–like bill in the 2019 legislative session. In New York City in April, a proposal to freeze rents for nearly one million rent-stabilized apartments was defeated after the city’s main trade group for residential landlords, the Rent Stabilization Association, reportedly spent over $1 million on lobbying in 2017.

To owners, landlord groups seek to portray renters as poor, unpredictable, and conniving. A mailer sent out to condo owners across Boston by the Small Property Owners Association in 2017 warned owners that if tenant protection legislation were to pass, “[d]isruptive renters will learn they can do anything with no consequences, no fines, no evictions.” It added, “Unevictable renters can pass their units & low rents on to their heirs. It never ends.”

To renters, real estate groups characterize rent control as anti-renter. In one recent ad, the executive director of the deceptively named California Council for Affordable Housing tells voters that Prop 10 will “drive up rents, take rental housing off the market, and make it harder to find a place to live.” Amy Schur of the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment, one of the organizations leading the “Yes” campaign on Prop 10, explains, “They are using that message because they read the same polls we read, which show that a majority of likely voters in California support rent control and want fast action to prevent rent gouging.” A 2017 poll by the Institute of Governmental Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, found that 60 percent of likely voters in the state support rent control. In Oregon, a research firm this past May found that nearly two-thirds of those surveyed support expanding rent regulations.

The anti–rent control rhetoric rests on the argument that rent control discourages developers from constructing new buildings, further aggravating housing shortages. But advocates say that landlord groups are blowing this threat out of proportion. Of all of the cities that have floated rent control legislation in the past few years, none have proposed extending rent control to include new construction. Even officials in Berkeley—who have been some of the strongest proponents of rent control—have proposed transitioning apartments into rent control on a rolling basis, exempting newly constructed buildings for 20 years. And, a report published out of University of Southern California last week shows that cities with rent stabilization ordinances for existing units have seen no decline in new construction.

Studies have indeed shown that rent control can affect existing housing stock—but for reasons real estate groups avoid spelling out. By taking advantage of loopholes for averting rent control requirements, landlords end up pulling more properties from the rental market, converting rent-regulated apartments into condos and reducing the overall supply of affordable housing. While rent control advocates acknowledge these risks, they maintain that rent control is necessary as a stopgap measure for tenants facing eviction in an extremely hostile rental market. Even a widely cited recent paper highlighting the potential negative effects of rent control found that, of tenants in San Francisco, beneficiaries of rent control are between 10 and 20 percent more likely to have remained in the same apartment since 1994 and that “absent rent control essentially all of those incentivized to stay in their apartments would have otherwise moved out of San Francisco.”

Despite these benefits, the real estate lobby’s scare tactics appear to be working. A poll this week shows that 46 percent of likely voters oppose Proposition 10 and only 35 percent are in favor. “We are finding voters in our community who are crystal clear that they support rent control, and then say, ‘So we should vote no on Prop 10, right?’” says Schur. In Mountain View, this summer, San Jose Inside reported that nearly 300 voters had been misled by paid signature-gatherers (some of whom said they were paid $40 per signature) into thinking that a rent control bill was pro-rent control, when in fact it aimed to repeal a rent control ordinance.

In some ways this is an old story. “The mobilization of networks of local politicians and homeowners, the explicit use of race and class stereotypes, the references to renters as second-class citizens,” says Tony Roshan Samara of Urban Habitat, a grassroots advocacy organization for low-income communities of color in the Bay Area. “All of this goes back to ‘30s, ‘40s, ‘50s. We’re seeing the same politics of who gets to control land and who doesn’t.”

But the scale of today’s opposition campaign is a distinctly post–financial crisis phenomenon, dictated by a race-to-the-bottom rental market. Since 2013, private equity firms like Blackstone have been purchasing tens of thousands of homes, converting them into rental properties, and bundling and securitizing them to create triple A–rated “single-family rental bonds.” Unlike “mom-and-pop” landlords, who tend to rely on a single-fixed rate loan from a bank, this new model relies on big investments from Wall Street investors, who expect firms to extract ever-higher returns from their tenants.

“The financialization of the rental housing market has had profound ramifications,” explains Schur. “This is rip and run—the Blackstones of the world are not investing long-term in our communities, they are extracting wealth from California to give to investors in the global financial market.” The impact of legislation like Proposition 10 on a local landlord is nominal compared to the impact on a group like Blackstone, which has a portfolio of around 13,000 single-family rentals in California and a 40 percent stake in Invitation Homes, a property management group with another 13,000 homes in the state.

The viability of this profit structure relies on a great degree of political intervention, not just in ballot initiatives, but also into elected offices across the country. In Oregon, filings from the secretary of state’s office show that the More Housing Now! PAC and its member organizations have contributed thousands of dollars to help County Commissioner Loretta Smith defeat vocally pro-tenant candidate Jo Ann Hardesty for one of Portland’s open city council seats. The PAC of the California Apartment Association, one of the groups behind the No on Prop 10 campaign, was among the top donors to the campaigns of incumbent candidates in four different city council districts in Sacramento, all four of whom won reelection. And there’s likely far more money flowing behind the scenes: In 2015, the Mountain View Voice reported that the California Apartment Association had quietly funneled $90,000 to three city council candidates opposed to rent control through a PAC called Neighborhood Empowerment Coalition.

For tenant advocates working to advance rent control across the country, these tactics haven’t come as a big surprise. “Everyone expected to be out-funded by the real estate industry. It’s just standard practice, especially during a housing crisis, when rents are really high,” says Singh of Tenants Together. This election may be the first where the landlord lobby’s influence has emerged into full view, but as campaigns at all levels of government continue to embrace affordable housing as one of the most pressing domestic policy questions, it won’t be the last.

If this is what it takes to make Julia Davis a very rich woman, then so be it. The extraordinary writer and actress got her start on British TV in the 1990s, when she sent a character reel to Steve Coogan, who hired her as a writer. The first show she wrote was the BAFTA-winning Nighty Night, a pitch-black comedy about a narcissist (played by Davis) who uses her husband’s cancer to manipulate people around her. In 2016, Davis wrote a six-episode series for Sky Atlantic called Camping, about a starchy monster of a mom who organizes a camping trip for her family and two other couples. That show has now been snapped up by HBO and remade to gleaming American standards by Girls creators Lena Dunham and Jenni Konner.

It’s premiered to some fairly harsh reviews, all of which entirely miss the point. Camping, in its original incarnation, was a vicious satire about a middle-aged harridan who micromanages a trip at a campground run by a deranged mama’s boy. Her browbeaten husband joins her, as well as a son who is forced to wear a special helmet in case he gets injured. Also present is the mother’s pathetic sister, who brings along her boyfriend, a reformed alcoholic widower (his teenager comes with them). The third couple is a recently-separated young man and his brand new girlfriend, a nymphomaniac (played to perfection by Davis herself) who offers everybody speed or ketamine, sometimes mixing them up.

The jokes are blindingly cruel. The alcoholic starts drinking again, provoked by the nympho, and argues with another guy about his dead wife. “She drowned to death!” his friend cries. “Yeah,” he responds. “It’s like, watch where you’re going you stupid cow.” The overprotective mother takes her kid to the hospital after he gets a bump to the head. “I wonder if you wouldn’t mind having a quick look at his anus,” she asks the doctor. “I’m worried that he might have more than one.”

The miniature society of the camping trip totally breaks down. Repulsive sex ensues, along with diabolical mishaps, nudity, violence, and drug benders. The show isn’t so much dark as completely, disorientingly devoid of light.

Julia Davis in the original Camping.Sky Atlantic

Julia Davis in the original Camping.Sky AtlanticDunham and Konner have now remade the show for an American audience that is notoriously thinner-skinned than its British counterpart. It’s interesting to see what they’ve kept and what they’ve discarded. All the basic characters are there, played by a very starry cast: The micromanaging mom is Kathryn (Jennifer Garner). Her downtrodden husband is Walt (David Tennant, playing American). Miguel (Arturo del Puerto) is the newly separated horndog, with Jandice (Juliette Lewis) his boundary-trampling girlfriend. The innocent little sister is Carleen (Ione Skye), and her addict boyfriend is Joe (Chris Sullivan). They’ve added another couple to the mix, in the form of Nina-Joy and George (Janicza Bravo and Brett Gelman), to be foils to the other couples’ bad behavior.

The central change is that Dunham and Konner have imbued each character with a sympathetic twist. Kathryn still micromanages—forcing everybody to go bird-watching, for example—but now she’s a woman stricken by grief over her hysterectomy, her emotional dysfunction sublimated into worries over her body (echoing Dunham’s own medical woes). The brainless and nasty alcoholic of the British Camping has become a sweet, struggling guy who is just trying to find his way. Miguel the shagger is now a smart doctor finding a new light in his life, instead of a pathetic young Englishman who got hair plugs and speaks with a slight American accent.

Crucially, the girlfriend who shows up out of the blue to destabilize the group is now a toxic Reiki healer, rather than Davis’s dubstep DJ. In the original, Fay (Davis) is an irredeemable nightmare. In the new show, Juliette Lewis as Jandice gives us a character who is equally maddening but also charming. In this show, her oversteps sometimes really do liberate the uptight campers around her. She convinces Carleen to cut her hair, for example, and Carleen loves it. Lewis is by far the best actor in the cast, and she certainly has the best role to play with. She gets to be outlandish, horrible, and gorgeous, then flounce off into the fields aglow with hippie self-righteousness.

All these changes are more than acceptable. There is nothing on American television with the vinegar of the original Camping, and to my great sadness there probably will never be. Dunham and Konner’s light touch has allowed them to keep huge chunks of the original script. In fact, many of the jokes are exactly the same. “Velcome to ze camps!” both dads joke, to their wives’ chagrin. We are still allowed to hate everybody, just in lesser doses.

Sadly, the writers cut the best joke of the original script. The mother in the U.K. show won’t let her son eat sun-dried tomatoes, or mozzarella, or wraps, because she fears they will make him “a homosexual.” “They’ve found a link,” she spits, referring to some kind of imaginary science. Making the tyrannical mom into a homophobe is the perfect detail, an evil cherry on top of a very evil cake. The cut is symptomatic of the new show’s agenda: We can’t have Kathryn hate gay people if she is to be ultimately redeemable. We’ve got to keep the hope alive, or nobody will keep watching.

Almost every major review in the U.S. so far has bemoaned the painfulness of the Camping experience. In The New York Times, James Poniewozik lamented that “Camping could be a cutting social satire. ... But it’s hard to see past the harsh filter.” At Variety, Caroline Framke wrote that “the series wastes its potential, showing so little insight or movement that watching Camping becomes nearly as unpleasant as it is for the characters living through it.”

But great satire is meant to be unpleasant. It’s supposed to make your soul feel the way your mouth does when it fills with bile. When you have that feeling and then you laugh, it has the taste of truth. The new Camping has had some of the old force taken out of its swing, but now and then it delivers a real, live uppercut. A show like this should be a tussle: between viewer and character, between love and hate, between enjoyment and pain. Camping could be nastier still, but at least the fight is there.

The U.S. stock market’s weeklong decline reversed itself dramatically on Tuesday, producing one of the strongest climbs of the year. A gain driven by strong earnings reports from bulwarks like Goldman Sachs and Johnson & Johnson pushed the market, which had lost 1,600 points in the previous eight trading days, up nearly 600 points. While the Dow Jones still sits about 1,100 points shy of its early October high, the gains have calmed fears that the nearly decade-long bull market was coming to an end.

But if Wall Street was breathing easy on Tuesday, the media didn’t notice. Instead, cable news focused on the disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the upcoming midterm elections, and President Donald Trump’s Twitter feed, where he called his alleged former mistress “horseface.” On Wednesday, in an attempt to work the refs, Trump called out the media for ignoring the market’s gains, implying that he should be given credit for them.

“Network News gave Zero coverage to the Big Day the Stock Market had yesterday.” @foxandfriends

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 17, 2018But the media isn’t alone in ignoring good news about the market or the economy more broadly. After tethering himself to the stock market for most of his first year in office, Trump has distanced himself from its performance since February’s nosedive. And after spending the first half of the year planning to campaign on the $1.5 trillion tax cut passed in late-December, since midsummer congressional Republicans have all but ignored their top legislative achievement of the Trump era. It’s now clear that, far from being a boon, the tax cut is a liability for Republicans, with Democrats using it as proof of the party’s upper-crust loyalties. Handed the strongest economy since the mid-’90s, the GOP instead has decided to campaign much like its leader did in 2016: on a platform of fear.

Back in February, Republicans planned a midterm strategy centered on the $1.5 trillion tax cut (which they promised, to much skepticism, would reduce the deficit) and on the strong economy (which they had inherited from President Barack Obama). “The tax bill is part of a bigger theme that we’re going to call The Great American comeback,” National Republican Congressional Committee chairman Steve Stivers told Bloomberg. “If we stay focused on selling the tax reform package, I think we’re going to hold the House and things are going to be OK for us.” In the weeks and months after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was narrowly enacted, Trump and other Republicans relentlessly flaunted the law as evidence of the party’s fiscal bona fides.

The message was supposed to be simple. “Congress has reached an agreement on tax legislation that will deliver more jobs, higher wages and massive tax relief for American families and for American companies,” Trump promised after congressional Republicans finalized the bill in December. Concerns about the potential adverse effects of passing a $1.5 trillion tax cut during a rosy economic period—namely that it would balloon the deficit—were dismissed, despite the presence of numerous nonpartisan studies arguing that the national debt would increase by as much as $2 trillion. White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney told CNN he thought the bill “actually generates money,” while Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin argued “the plan will pay for itself through growth.” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell told reporters, “We fully anticipate this tax proposal in the end to be revenue neutral for the government, if not a revenue generator.”

While the tax cut appeared to add rocket fuel to a booming stock market, Republicans were never able to connect it to perceptions about the overall health of the economy. Most voters, a recent Gallup poll show, do not discern any change in their economic well-being tied to the tax cut, while an internal GOP Bloomberg poll found that voters, by a two-to-one margin, believed the cuts favored corporations and the wealthy. Democrats were more effective in messaging and instead reframed the law as what it (mostly) was: an unnecessary giveaway to corporations and the rich. “In terms of the bonus that corporate America received versus the crumbs they are giving to workers, to kind of put the schmooze is so pathetic, it’s so pathetic,” House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi said in a January press conference. Republicans pounced at the time, thinking they had caught Pelosi making an elitist remark. But nearly a year later, many voters agree with Pelosi.

On Tuesday, the Treasury Department announced that the deficit had increased by nearly $800 billion—a jump of 17 percent—thanks in large part to declining tax revenue. The leap was the largest since 2009, at the height of the Great Recession. In April, the CBO released a report finding that the deficit would hit $1 trillion by 2020—two years earlier than initially thought. The rising deficit has caused Republicans, predictably, to call for entitlement reform—meaning cuts to Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. Ever the cynic, McConnell this week deflected reports that the GOP tax cut was driving the debt increase and instead suggested that entitlement programs were the real deficit busters. “It’s disappointing, but it’s not a Republican problem,” McConnell told Bloomberg on Tuesday. “It’s a bipartisan problem: Unwillingness to address the real drivers of the debt by doing anything to adjust those programs to the demographics of America in the future.”

But this has only fueled Democratic midterm messaging about potential GOP cuts to social spending. “Sen. McConnell gave the game up in his comment yesterday,” Maryland senator Chris Van Hollen, who chairs the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, said in a press call on Wednesday. “It was very clear from what he said that a vote for Republican candidates in this election is a vote to cut Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. That’s what he said.”

With voters dismissing the meager benefits the tax cut bestowed on them, and the deficit ballooning, Republicans can’t claim ownership of an economic boom that’s been years in the making. So instead they’re embracing Trump’s 2016 playbook: fear-mongering over Muslims, immigration, and crime. In the wake of the protests against Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court, Republicans have argued, sometimes explicitly, that they must be kept in power to preserve the rule of law—that Democrats will burn everything to the ground if they’re put in charge. “You don’t hand matches to an arsonist, and you don’t hand power to an angry, left-wing mob, and that’s what they have become,” Trump recently said.

Republicans also may be realizing what Hillary Clinton’s campaign realized too late in 2016: The economy is strong by most metrics, but millions of voters don’t see it that way. Though the economy Trump inherited was booming, its gains were being reaped unequally—that’s partly why he won. Touting a strong economy to voters who have been left behind is far from a winning strategy, especially after passing a tax cut for the rich that has only made that inequality more pronounced.

All of this may be beside the point. Republicans hurried to enact the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in part to please their donors, whose help they needed to fend off a blue wave in 2018. Sure enough, donors like Sheldon Adelson and the Koch brothers have opened their checkbooks, but Republicans are getting pummeled in fundraising in dozens of competitive districts: Democrats have out-raised Republicans in all 30 “tossup” races, according to FEC data released on Tuesday. Still, that money has done nothing to boost Republican efforts to sell the economy or the tax bill. “Their messaging has been extremely poor,” Steve Moore, who served as an economic adviser to Trump’s 2016 campaign, told The Washington Post. “We’ve got the best economy in 25 years and they aren’t really talking about it. They are letting Democrats control the messaging.”

In April, when the Senate Judiciary and Commerce committees summoned Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg to Washington, it looked as if the nation was finally going to reckon with the outsize role that technology companies now play in American elections. Seventeen months had gone by since Donald Trump’s stunning presidential victory—a success credited by many to his campaign’s mastery of Facebook’s advertising platform, as well as to the divisive agitprop seeded throughout Facebook by Russian trolls from the Internet Research Agency, whose 470 pages and accounts were seen by an estimated 157 million Americans.

But that was not what brought Zuckerberg to the Capitol. Instead, he was there to diffuse the bomb dropped three weeks earlier by Christopher Wylie, former research director at Cambridge Analytica, the data science firm that Trump’s digital team had employed during the election campaign. In interviews with The Guardian and The New York Times, Wylie confirmed that his company had taken data from millions of Facebook users without their knowledge or consent—as many as 87 million users, he later revealed. Cambridge Analytica had used the information to identify Americans’ subconscious biases and craft political messages designed to trigger their anxieties and thereby influence their political decisions—recasting a marketing technique known as “psychographics” that, more typically, is used to entice retail customers with ads that spark their underlying emotional reflexes. (“This product will make you feel happy!” “This product will make you feel attractive!”)

Cambridge Analytica turned this technique sideways, with messaging that exploited people’s vulnerabilities and psychological proclivities. Those with authoritarian sympathies might have received messages about gun rights or Trump’s desire to build a border wall. The overly anxious and insecure might have been pitched Facebook ads and emails talking about Hillary Clinton’s support for sanctuary cities and how they harbor undocumented and violent immigrants. Alexander Nix, who served as CEO of Cambridge Analytica until March, had earlier called this method of psychological arousal the data firm’s “secret sauce.”

Cambridge Analytica had purchased its Facebook user data for more than $800,000 from Global Science Research (GSR), a company that was set up specifically to access the accounts of anyone who clicked on GSR’s “This Is Your Digital Life” app—and the accounts of their Facebook friends. At the time, Facebook’s privacy policy allowed this, even though most users never consented to handing over their data or knew that it had been harvested and sold. The next year, when it became aware that Cambridge Analytica had purchased the data, Facebook took down the GSR app and asked both GSR and Cambridge Analytica to delete the data. “They told us they did this,” Zuckerberg told Congress. “In retrospect, it was clearly a mistake to believe them.” In March, around the time Wylie came forward, The New York Times reported that at least some of the data was still available online.

Wylie, a pink-haired, vegan, gay Canadian, might seem an unlikely asset to Trump’s campaign. And as he tells the story now, he’s filled with remorse for creating what, in an interview with The Guardian, he referred to as “Steve Bannon’s psychological warfare mindfuck tool.” For months, he had been quietly feeding information to the investigative reporter Carole Cadwalladr, whose articles in The Guardian and The Observer steadily revealed a through-line from dark money to Cambridge Analytica to Trump. (Cadwalladr also connected Cambridge Analytica to the Brexit campaign, through a Canadian data firm that worked both for the Vote Leave campaign and for Cambridge Analytica itself.) When he finally went public, Wylie explained how, with financial support from right-wing billionaire Robert Mercer, Cambridge Analytica’s principal investor, and with Steve Bannon’s guidance, he had built the algorithms and models that would target the innate biases of American voters. (Ted Cruz was one of Cambridge Analytica’s first clients and was Mercer’s preferred presidential candidate in the primaries before Trump crushed him.) In so doing, Wylie told Cadwalladr, “We ‘broke’ Facebook.”

So Zuckerberg agreed to come to Washington to be questioned by senators about the way his company’s lax privacy policies had inadvertently influenced the U.S. election—and possibly thrown it to Donald Trump. But what should have been a grilling turned out to be more like a sous vide—slow, gentle, low temperature—as the senators lightly rapped Zuckerberg on his knuckles over Facebook’s various blunders, and he continually reminded them that he’d created the site in his Harvard dorm room, not much more than a decade before, and now look at it! Of course, he reminded them with a kind of earnest contrition, there were going to be bumps in the road, growing pains, glitches. The senators seemed satisfied with his shambling responses and his constant refrain of “My team will get back to you,” and only mildly bothered when he couldn’t answer basic questions like the one from Roger Wicker, a Mississippi Republican, who wanted to know if Facebook could track a user’s internet browsing activity, even when that person was not logged on to the platform. (Answer: It can and it does.)

Shortly before this tepid inquest, Zuckerberg publicly endorsed the Honest Ads Act, a bipartisan bill cosponsored by Democratic Senators Amy Klobuchar and Mark Warner and Republican John McCain, which, among other things, would require internet platforms like Facebook to identify the sources of political advertisements. It also would subject online platforms and digital communications to the same campaign disclosure rules as television and radio.

A tech executive supporting federal regulation of the internet may, at first, seem like a big deal. “I’m not the type of person that thinks all regulation is bad,” Zuckerberg told the senators. “I think the internet is becoming increasingly important in people’s lives, and I think we need to have a full conversation about what is the right regulation, not whether it should be or shouldn’t be.” But Facebook has spent more than $50 million since 2009 lobbying Congress, in part to keep regulators at a distance, and cynics viewed Zuckerberg’s support for the new law as a calculated move to further this agenda. (Indeed, after California passed the strongest data privacy law in the country in June, Facebook and the other major tech companies began lobbying the Trump administration for a national, and far less stringent, data privacy policy that would supersede California’s.) Verbally supporting the Honest Ads Act— legislation that is unlikely to be enacted in the current atmosphere of the Congress—was easy, especially when Facebook had already begun rolling out a suite of new political ad policies that appeared to mirror the minimal transparency requirements lawmakers sought to establish. The subtext of this move was clear: Facebook could regulate itself without the interference of government overseers.

Zuckerberg’s congressional testimony was the culmination of an extensive apology tour in which he gave penitent interviews to The New York Times, Wired, Vox, and more, acknowledging that mistakes had been made. “This was a major breach of trust,” Zuckerberg told CNN. “I’m really sorry that this happened.” A month later, Facebook launched a major ad campaign, vowing, “From now on, Facebook will do more to keep you safe and protect your privacy.” Then, in mid-May, Cambridge Analytica declared bankruptcy, though this did not put an end to the whole affair. A legal challenge to the company by American professor David Carroll for processing his voter data without his knowledge or consent has been allowed to continue in the U.K., despite the firm’s dissolution.

Republican and Democratic data firms are hard at work on the next generation of digital tools—driven by the idea that political campaigns can identify and influence voters by gathering as much data about them as possible.

It’s impossible to know whether Cambridge Analytica’s psychographic algorithms truly made a difference in Trump’s victory. But the underlying idea—that political campaigns can identify and influence potential voters more effectively by gathering as much information as possible on their identities, beliefs, and habits—continues to drive both Republican and Democratic data firms, which are currently hard at work on the next generation of digital campaign tools. And while the controversy surrounding Cambridge Analytica exposed some of the more ominous aspects of election campaigning in the age of big data, the revelations haven’t led to soul-searching on the part of tech companies or serious calls for reform by the public—and certainly not from politicians, who benefit most from these tactics.

If anything, the digital arms race is accelerating, spurred by advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning, as technologists working both sides of the political aisle develop ever-more-powerful tools to parse, analyze, and beguile the electorate. Lawmakers in Congress may have called Mark Zuckerberg to account for Facebook’s lax protection of its users’ data. But larger and more enduring questions remain about how personal data continues to be collected and used to game not just the system, but ourselves as sovereign individuals and citizens.

In 1960, John F. Kennedy’s campaign manager—his brother Robert—hired one of the first data analytics firms, the Simulmatics Corporation, to use focus groups and voter surveys to tease out the underlying biases of the public as the country considered whether to elect its first Catholic president.

The work was top secret; Kennedy denied that he’d ever commissioned the Simulmatics report. But in the decades that followed, as market researchers and advertisers adopted psychological methods to better understand and appeal to consumers, social scientists consulting on political campaigns embraced the approach as well. They imagined a real-world political science fashioned out of population surveys, demographic analyses, psychological assessments, message testing, and algorithmic modeling. It would be a science that produced rational and quantifiable strategies to reach prospective voters and convert them into staunch supporters. That goal—merely aspirational at the time—has since developed into a multibillion-dollar industry, of which Cambridge Analytica was a well-remunerated beneficiary. For its five-month contract with the Trump campaign in 2016, the company was paid nearly $6 million.

The kind of work Cambridge Analytica was hired to perform is a derivative of “micro-targeting,” a marketing technique that was first adapted for politics in 2000 by Karl Rove, George W. Bush’s chief strategist. That year, and to an even greater degree in 2004, Rove and his team set about finding consumers—that is to say, voters—who were most likely to buy what his candidate was selling, by uncovering and then appealing to their most salient traits and concerns. Under Rove’s guidance, the Bush team surveyed large samples of individual voters to assess their beliefs and behaviors, looking at such things as church attendance, magazine subscriptions, and organization memberships, and then used the results to identify 30 different kinds of supporters, each with specific interests, lifestyles, ideologies, and affinities, from suburban moms who support the Second Amendment to veterans who love NASCAR. They then slotted the larger universe of possible Bush voters into those 30 categories and tailored their messages accordingly. This approach gave the Bush campaign a way to supplement traditional broadcast media by narrowcasting specific messages to specific constituencies, and it set the scene for every campaign, Republican and Democratic, that followed.

In 2008, the micro-targeting advantage shifted to the Democrats. Democratic National Committee Chair Howard Dean oversaw the development of a robust database of Democratic voters, while for-profit data companies were launched in support of liberal causes and Democratic candidates. Their for-profit status allowed them to share data sets between political clients and advocacy groups, something the DNC could not do with its voter database because of campaign finance laws. One of these companies, Catalist, now controls a data set of 240 million voting-age individuals, each an aggregate, the company says, of hundreds of data points, including “purchasing and investment profiles, donation behavior, occupational information, recreational interests, and engagement with civic and community groups.”

“Catalist was a game changer,” said Nicco Mele, the director of Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy, and a veteran of dozens of political campaigns. “It preserved data in an ongoing way, cycle after cycle, so it wasn’t lost after every campaign and didn’t have to be re-created for the next one. Catalist got things going.”

The data sets were just one part of it. In 2008 and 2012, the Democrats also had more sophisticated predictive models than the Republicans did, a result of having teams of data scientists and behavioral scientists advising Barack Obama’s presidential campaigns. While the data scientists crunched the numbers, the behavioral scientists conducted experiments to determine the most promising ways to get people to vote for their candidate. Shaming them by comparing their voting record to their family members and neighbors turned out to be surprisingly effective, and person-to-person contact was dramatically more productive than robocalls; the two combined were even more potent.

The Obama campaign also repurposed an advertising strategy called “uplift” or “brand lift,” normally used to measure consumer-brand interactions, and used it to pursue persuadable voters. First they gathered millions of data points on the electorate from public sources, commercial information brokers, and their own surveys. Then they polled voters with great frequency and looked for patterns in the responses. The data points, overlaid on top of those patterns, allowed the Democrats to create models that predicted who was likely to vote for Obama, who was not, and who was open to persuasion. (The models also indicated who would be disinclined to vote for Obama if contacted by the campaign.) These models sorted individuals into categories, as the Bush campaign had done before— mothers concerned about gun violence, say, or millennials with significant college debt—and these categories were then used to tailor communications to the individuals in each group, which is the essence of micro-targeting.

The Obama campaign had another, novel source of data, too: information that flowed from the cable television set-top boxes in people’s homes. Through agreements with industry research firms, the campaign sent them the names and addresses of individuals whom their models tagged as persuadable, and the research companies sent back anonymous viewing profiles of each one. The campaign used these profiles to identify which stations and programs would give them the most persuasion per dollar, allowing them to buy ads in the places and times that would be most effective. The campaign also mined—and here’s the irony—Facebook data culled from the friends of friends, looking for supporters.

“To be a technology president used to be a very cool thing,” said Zac Moffatt, who ran Mitt Romney’s 2012 digital campaign. “And now it’s a very dangerous thing.”The fact that the Obama campaign was able to use personal information in this way without raising the same ire as Cambridge Analytica and Facebook is a sign of how American views on technology and its role in politics have shifted over the past decade. At the time, technology was still largely viewed as a means to break traditional political structures, empower marginalized communities, and tap into the power of the grassroots. Today, however, many people have a much darker view of the role technology plays in politics—and in society as a whole. “In ’12 we talked about Obama using micro-targeting to look at your set-top box to tell you who should get what commercial, and we celebrated it,” said Zac Moffatt, who ran Mitt Romney’s digital campaign in that election. “But then we look at the next one and say, ‘Can you believe the horror of it?’ There’s an element of the lens through which you see it. To be a technology president used to be a very cool thing, and now it’s a very dangerous thing.”

Despite the innovations of both Obama campaigns, by the time the 2016 election season rolled around, the technological advantage had shifted back to the Republicans, who had developed a sophisticated, holistic approach to digital campaigning that benefited not only Donald Trump but down-ticket Republicans as well. Republicans had access to a revamped GOP Data Center run by the party, as well as to i360, a for-profit data operation bankrolled by the Koch brothers’ network that offered incredibly detailed information on potential voters. The i360 voter files combined information purchased from commercial sources, such as shopping habits, credit status, homeownership, and religious affiliation, with voting histories, social media content, and any connections a voter might have had with advocacy groups or other campaigns. To this, Politico reported in 2014, the Koch network added “polling, message-testing, fact-checking, advertising, media buying, [and] mastery of election law.” Democratic candidates, meanwhile, were largely beholden to the party’s official data provider, NGP VAN, with the DNC not only controlling the data, but deciding how it could be used and by whom.

In 2016, the technological advantage shifted to the Republicans. Now, however, Higher Ground Labs, a campaign-tech incubator, is trying to make Democrats competitive again.The Obama team’s digital trailblazing also may have diverted attention from what the Republicans were actually up to during those years. “I think 2016 was kind of the realization that you had eight years of reporters believing everything told them by the Democratic Party—‘We know everything, and the Republicans can’t rub two rocks together,’” Moffatt said. “But if you look, the Republicans haven’t really lost since 2010, primarily based on their data fields and technology. But no one wanted to tell that story.”

One major plot-point in that story’s arc is that the Republican Party devoted more resources to social media and the internet than the Democrats did. Eighty percent of Trump’s advertising budget went to Facebook in 2016, for example. “The Trump campaign was fully willing to embrace the reality that consumption had moved to mobile, that it had moved to social,” Moffatt said. “If you think about Facebook as the entry point to the internet and a global news page, they dominated it there, while Hillary dominated all the places campaigns have historically dominated”—especially television.

Clinton’s loss hasn’t changed the basic strategy, either. Going into the midterms, Republicans continue to focus on the internet, while Democrats continue to pour money into television. (An exception is the Democratic-supporting PAC Priorities USA, which is spending $50 million on digital ads for the midterms.) Republicans are reportedly spending 40 percent on digital advertising, whereas Democrats are spending around 10 percent to 20 percent. Democratic strategist Tim Lim agrees that ignoring the internet in favor of television advertising is a flawed strategy. “The only way people can actually understand what we’re running for is if they see our messaging, and they’re not going to be seeing our messaging if we’re spending it on Wheel of Fortune and NCIS,” he said. “Democratic voters are not watching those shows.”

The Democrats are hampered by a structural problem, too: Each campaign owns its own digital tools, and when an election is over, those tools are packed up and put away. As a result, said Betsy Hoover, a veteran of both Obama campaigns who is now a partner at Higher Ground Labs, a liberal campaign-tech incubator, “four years later we’re essentially rebuilding solutions to the same problem from square one, rather than starting further up the chain.” The Republicans, by contrast, have been building platforms and seeding them up and down the party—which has allowed them to maintain their technological advantage.

“After losing in 2012, one of the most creative things the Republicans did was apply entrepreneurship to technology,” said Shomik Dutta, Hoover’s partner in Higher Ground Labs, who also worked on both Obama campaigns as well as in the Obama White House. “The Koch brothers funded i360, and the Mercers funded Cambridge Analytica and Breitbart, and they used entrepreneurship to take risks, build products, test them nimbly, and then scale up what worked quickly across the party. And that, I think, is a smart way to think about political technology.”

And so, taking a page from the Republican playbook, for the past two years Hoover and Dutta have been working to make Democrats competitive again in the arena of campaign technology. In the absence of deep-pocketed Democratic funders comparable to the Mercers and the Kochs, Higher Ground Labs acts as an incubator, looking particularly to Silicon Valley entrepreneurs to support the next generation of for-profit, election-tech startups. In 2017, the company divided $2.5 million in funding between eleven firms, and in April it announced that it was giving 13 additional startups an average of $100,000 each in seed money.

That’s still a far cry from the $50 million the Koch brothers reportedly spent to develop i360. And Higher Ground Labs faces other challenges, too. Political candidates and consultants are often creatures of habit, so getting them to try new products and untested approaches can be difficult. With presidential elections happening only every four years, and congressional elections happening every two, it can be difficult for election tech companies to sustain themselves financially. And, as has been the case with so many technology companies, growing from a small, nimble startup into a viable company that can compete on a national level is often tricky. “It’s easy to create a bunch of technology,” said Robby Mook, Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign manager, “but it’s a lot harder to create technology that creates the outcomes you need at scale.”

Hoover and Dutta are hopeful that their investments in these startups will pay off. If the companies make money, Higher Ground Labs will become self-sustaining. But even if the startups fail financially, they may show what’s possible technologically. Indeed, the new tools these companies are working on are a different order of magnitude from the searchable databases that companies like Catalist pioneered just a few election cycles ago. And if they help Democratic candidates win, Hoover and Dutta view it as money well spent. “We hope to be part of the cavalry,” Hoover said.

The companies that Higher Ground Labs is funding are working on all aspects of campaigning: fundraising, polling, research, voter persuasion, and get-out-the-vote efforts. They show where technology—especially artificial intelligence, machine learning, and data mining—is taking campaigning, not unlike Cambridge Analytica did two years ago when it launched “psychographics” into the public consciousness. One Higher Ground-funded company has developed a platform that uses web site banner ads to measure public opinion. Another is able to analyze social media to identify content that actually changes minds (as opposed to messages that people ignore). A third has created a database of every candidate running for office across the country, providing actionable information to state party operatives and donors while building a core piece of infrastructure for the Democrats more generally.

An opposition research firm on Higher Ground’s roster, Factba.se, may offer campaigns the antidote to fake news (assuming evidence still matters in political discourse). It scours documents, social media, videos, and audio recordings to create a searchable compendium of every word published or uttered online by an individual. If you want to discover everything Donald Trump has ever said about women or steak or immigrants or cocaine, it will be in Factba.se. If you want to know every time he’s contradicted himself, Factba.se can provide that information. If you want to know just how limited his verbal skills are, that analysis is available too. (The president speaks at a fourth-grade level.) And if you want to know what’s really bugging him—or anyone—Factba.se uses software that can evaluate audio recordings and pick up on expressions of stress or discomfort in a person’s voice that are undetectable to the naked eye or ear.

To augment its targets’ dossiers, the company also uses personality tests to assess their emotional makeup. Is the subject extroverted, neurotic, depressed, or scared? Is he all of the above? (One of these tests, OCEAN—designed to measure openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—is actually the same one that Cambridge Analytica used to construct its models.)

“We build these profiles of people based upon everything they do,” said Mark Walsh, the CEO of FactSquared. “Our AI engine can be quite predictive of what makes you happy and what makes you sad.”“We build these profiles of people based upon everything they do, and then we do an analysis,” said Mark Walsh, the CEO of Factba.se’s parent company FactSquared, who was the first chief technology officer of the Democratic Party, back in 2002. As an example, he cited the 2017 gubernatorial race in Virginia, where Ed Gillespie, the former head of the Republican National Committee, ran against Lt. Governor Ralph Northam. “We took audio and video of the three debates, and we analyzed Gillespie, looking for micro-tremors and tension in his voice when he was talking about certain topics,” Walsh said. “If you were watching the debates, you wouldn’t know that there was a huge spike when he was talking about his own party’s gun control policy, which he didn’t seem to agree with.” This was valuable intel for the Northam campaign, Walsh said—though in the end, Northam didn’t really need it. (Northam won the election by nearly nine points, the biggest margin for a Democrat in more than a quarter-century.) Still, it was a weapon that stood at the ready.

“These are the types of oppo things you’re going to start to see more and more of, where candidate A will be able to fuck with the head of candidate B in ways that the populace won’t know, by saying things that they know bothers them or challenges them or makes them off-kilter,” Walsh said. “After about 5,000 words, our AI engine can be quite predictive of what makes you happy and what makes you sad and what makes you nervous.”

Judging personalities, measuring voice stress, digging through everything someone has ever said—all of this suggests that future digital campaigns, irrespective of party, will have ever-sharper tools to burrow into the psyches of candidates and voters. Consider Avalanche Strategy, another startup supported by Higher Ground Labs. Its proprietary algorithm analyzes what people say and tries to determine what they really mean—whether they are perhaps shading the truth or not being completely comfortable about their views. According to Michiah Prull, one of the company’s founders, the data firm prompts survey takers to answer open-ended questions about a particular issue, and then analyzes the specific language in the responses to identify “psychographic clusters” within the larger population. This allows campaigns to target their messaging even more effectively than traditional polling can—because, as the 2016 election made clear, people often aren’t completely open and honest with pollsters.

“We are able to identify the positioning, framing, and messaging that will resonate across the clusters to create large, powerful coalitions, and within clusters to drive the strongest engagement with specific groups,” Prull said. Avalanche Strategy’s technology was used by six female first-time candidates in the 2017 Virginia election who took its insights and created digital ads based on its recommendations in the final weeks of the campaign. Five of the six women won.

Clearly, despite public consternation over Cambridge Analytica’s tactics, especially in the days and weeks after Trump won (and before its data misappropriation had come to light), political campaigns are not shying away from the use of psychographics. If anything, the use of deeply personal data is becoming even more embedded within today’s approach to campaigning. “There is real social science behind it,” Laura Quinn, the CEO of Catalist, told me not long after the 2016 election. “The Facebook platform lets people gather so much attitudinal information. This is going to be very useful in the future for figuring out how to make resource decisions about where people might be more receptive to a set of narratives or content or issues you are promoting.”

And it’s not just Facebook that provides a wealth of user information. Almost all online activity, and much offline, produces vast amounts of data that is being aggregated and analyzed by commercial vendors who sell the information to whoever will pay for it—businesses, universities, political campaigns. That is the modus operandi of what the now-retired Harvard business professor Shoshana Zuboff calls “surveillance capitalism”: Everything that can be captured about citizens is sucked up and monetized by data brokers, marketers, and companies angling for your business. That data is corralled into algorithms that tell advertisers what you might buy, insurance companies if you’re a good risk, colleges if you’re an attractive candidate for admission, courts if you’re likely to commit another crime, and on and on. Elections—the essence of our democracy—are not exempt.

The manipulation of personal data to advance a political cause undermines a fundamental aspect of American democracy: the idea of a free and fair election.Just as advertisers or platforms like Facebook and Google argue that all this data leads to ads that consumers actually want to see, political campaigns contend that their use of data does something similar: It enables an accurate ideological alignment of candidate and voter. That could very well be true. Even so, the manipulation of personal data to advance a political cause undermines a fundamental aspect of American democracy that begins to seem more remote with each passing campaign: the idea of a free and fair election. That, in the end, is the most important lesson of Cambridge Analytica. It didn’t just “break Facebook,” it broke the idea that campaigns work to convince voters that their policies will best serve them. It attempted to use psychological and other personal information to engage in a kind of voluntary disenfranchisement by depressing and suppressing turnout with messaging designed to keep voters who support the opposing candidate away from the polls—as well as using that same information to arouse fear, incite animosity, and divide the electorate.

“Manipulation obscures motive,” Prull said, and this is the problem in a nutshell: Technology may be neutral (this is debatable), but its deployment rarely is. No one cared that campaigns were using psychographics until it was revealed that psychographics might have helped put Donald Trump in the White House. No one cared about Facebook’s dark posts until they were used to discourage African Americans from showing up at the polls. No one noticed that their Twitter follower, Glenda from the heartland, with her million reasons to dislike Hillary Clinton, was really a bot created in Russia—until after the election, when the Kremlin’s efforts to use social media to sow dissension throughout the electorate were unmasked. American democracy, already pushed to the brink by unlimited corporate campaign donations, by gerrymandering, by election hacking, and by efforts to disenfranchise poor, minority, and typically Democratic voters, now must contend with a system that favors the campaign with the best data and the best tools. And as was made clear in 2016, data can be obtained surreptitiously, and tools can be used furtively, and no one can stop it before it’s too late.

Just as worrisome as political campaigns misusing technology are the outside forces seeking to influence American politics for their own ends. As Russia’s interventions in the 2016 election highlight, the biggest threats may not come from the apps and algorithms developed by campaigns, but instead from rogue operatives anywhere in the world using tools freely available on the internet.

Of particular concern to political strategists is the emerging trend of “deepfake” videos, which show real people saying and doing things they never actually said or did. These videos look so authentic that it is almost impossible to discern that they are not real. “This is super dangerous going into 2020,” Zac Moffatt said. “Our ability to process information lags behind the ability of technology to make something believable when it’s not. I just don’t think we’re ready for that.”

To get a sense of this growing threat, one only need look at a video that appeared on Facebook not long after the young Democratic Socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez won her primary for a New York congressional seat in June. The video appeared to be an interview with Ocasio-Cortez conducted by Allie Stuckey, the host of Conservative Review TV, an online political channel. Stuckey, on one side of the screen, asks Ocasio-Cortez questions, and Ocasio-Cortez, on the other, struggles to respond or gives embarrassingly wrong answers. She looks foolish. But the interview isn’t real. The video was a cut-and-paste job. Conservative Review TV had taken answers from a PBS interview with Ocasio-Cortez and paired them with questions asked by Stuckey that were designed to humiliate the candidate. The effort to discredit Ocasio-Cortez was extremely effective. In less than 24 hours, the interview was viewed more than a million times.

The Ocasio-Cortez video was not especially well made; a discerning viewer could spot the manipulation. But as technology improves, deepfakes will become harder and harder to identify. They will challenge reality. They will make a mockery of federal election laws, because they will catapult viewers into a post-truth universe where, to paraphrase Orwell, power is tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together again in new shapes of someone else’s thinking.

Facebook didn’t remove the offensive Ocasio-Cortez video when it was revealed to be a fake because Stuckey claimed—after the video had gone viral—that it was satirical; the company doesn’t take down humor unless it violates its “community standards.” This and other inconsistencies in Facebook’s “fake news” policies (such as its failure to remove Holocaust denier pages) demonstrate how difficult it will be to keep bad actors from using the platform to circulate malicious information. It also reveals the challenge, if not the danger, of letting tech companies police themselves.

This is not to suggest that the government will necessarily do a better job. It is quixotic to believe that there will be a legislative intervention to regulate how campaigns obtain data and how they use it anytime soon. In September, two months before the midterm elections, Republicans in the House of Representatives pulled out of a deal with their Democratic counterparts that would have banned campaigns from using stolen or hacked material. Meanwhile, the Federal Election Commission is largely toothless, and it’s hard to imagine how routine political messages, never mind campaign tech, could be regulated, let alone if they should be. Though the government has established fair election laws in the past—to combat influence peddling and fraud, for instance—the dizzying pace at which campaign technology is evolving makes it especially difficult for lawmakers to grapple with intellectually and legislatively, and for the public to understand the stakes. “If you leave us to do this on our own, we’re gonna mess it up,” Senator Mark Warner conceded this past June, alluding to his and his colleagues’ lack of technical expertise. Instead, Warner imagined some kind of partnership between lawmakers and the technology companies they’d oversee, which of course comes with its own complications.

If there is any good news in all of this, it is that technology is also being used to expand the electorate and extend the franchise. Democracy Works, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit, for example, has partnered with Facebook on a massive effort to register new voters. And more Americans— particularly younger people—are participating in the political process through “peer-to-peer” texting apps like Hustle on the left (which initially took off during the Bernie Sanders campaign), RumbleUp on the right, and CallHub, which is nonpartisan. These mobile apps enable supporters who may not want to knock on doors or make phone calls to still engage in canvassing activities directly.

This is key, because if there is one abiding message from political consultants of all dispositions, it is that the most effective campaigns are the most intimate ones. Hacking and cheating aside, technology will only carry a candidate so far. “I think the biggest fallacy out there right now is that we win through digital,” Robby Mook said. “Campaigns win because they have something compelling to say.”

Every state routinely prunes its voter rolls when registered voters move, die, or get convicted of a felony. But under Secretary of State Jon Husted, Ohio has taken an aggressive tack to removing voters from state registration lists. The state purged more than two million voters from its rolls between 2011 and 2016. Many, if not most of those voters were likely ineligible. But over the past few years, as part of an annual audit of sorts, Husted’s office has removed thousands of eligible voters from the rolls simply because they failed to vote in three consecutive elections and didn’t return a postcard confirming their registration.

Critics, including state Representative Kathleen Clyde, said this practice disproportionately affects low-income Ohioans and communities of color, two constituencies that typically favor Democratic candidates. In 2015, Clyde introduced a bill to block Husted from purging voters unless they leave the state. Two years later, she authored another bill that would enact automatic voter registration.

Neither measure became law in the Republican-led chamber. And this past June, the Supreme Court upheld Husted’s purge. But soon Clyde may be in a position to stop the practice herself: She’s the Democratic nominee to replace Husted as secretary of state, a position that would give her significant influence over the state’s election laws.

Clyde is one of roughly a dozen Democratic candidates across the country who could become their states’ chief election officers if a blue wave sweeps through polling places in November. Their victories would provide Democrats an opportunity to turn back voter suppression efforts by Republican officeholders—and could give the party a leg up in voter turnout when President Donald Trump is up for reelection in 2020.

Forty-seven states have a secretary of state, either as an appointed post or an elected office. While the position’s duties can vary from state to state, the most common duty is to oversee elections and voting procedures, which are shaped by a mixture of federal statutes, state laws, and county policies. Navigating that legal labyrinth often falls to secretaries of state—the hall monitor, of sorts, for the nation’s democratic processes.

The role has taken on a heightened significance in recent years. Republicans hold more than half of the positions across the country, giving the party an advantage when shaping the nation’s election processes. Some Republican secretaries of state have used the position to crusade against the purported threat of voter fraud. Though vanishingly rare in the U.S., voter fraud has provided a useful justification for more restrictive voting measures that have kept tens of thousands of Americans from exercising their right to cast a ballot.

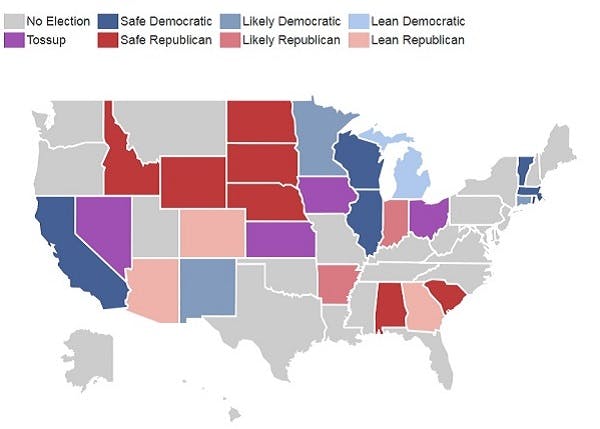

Governing magazine’s ratings of this year’s secretary of state races, as of October 12.

Governing magazine’s ratings of this year’s secretary of state races, as of October 12.Democrats have an opportunity in the November midterm elections to tear down those barriers. Roughly two-thirds of the nation’s elected secretary of state positions are on the ballot this year, and Republicans are defending seven open seats, versus none for Democrats. (Governing magazine has rated eight races as competitive—and all seats currently held by Republicans.) What’s more, the secretaries of state elected this year will serve during the 2020 presidential election, meaning that Democratic officeholders would be well-placed to expand voter access in battleground states like Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio, and Wisconsin should they prevail in two weeks.

Some contests have already drawn national attention. Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp, the Republican candidate for governor, froze 53,000 voter registration forms for dubious reasons, according to an Associated Press investigation earlier this month. More than 70 percent of the forms came from black applicants, raising concerns that the freeze is aimed at reducing voter turnout for Stacey Abrams, Kemp’s Democratic opponent. (If elected, Abrams would be the first black woman governor in American history.) Kemp also presided over a sweeping purge of the state’s voter rolls that removed almost 700,000 voters over the past two years.

Brad Raffensperger, the Republican candidate to replace Kemp, said at a debate earlier this month that he would continue the purges to “safeguard and keep our elections clean.” Jack Barrow, the Democratic challenger, opposes them. “Just because the Supreme Court allows you to discriminate doesn’t mean you must discriminate,” he wrote on Twitter after the court’s ruling in the Ohio case. “As your next Secretary of State, I’ll protect citizens who choose not to vote and keep them from being purged from voter rolls.” Barrow has also been critical of Kemp’s approach to election cybersecurity after Russian hackers targeted state election systems in 2016.

Kansas also moved to the center of the voting-rights wars after Kris Kobach’s election as secretary of state in 2010. He became a national spokesman of sorts for restrictive voting laws, championing the state’s strict voter ID law, successfully persuading Kansas lawmakers to let his office prosecute voter-fraud cases, and overseeing a dubious interstate anti-fraud program with a high false positive rate. His efforts to add a proof-of-citizenship requirement to the state’s voter registration forms sparked a legal showdown with the ACLU, which successfully argued in court that the move violated federal election law. A federal judge found Kobach in contempt earlier this year for failing to register voters who had been previously blocked by the requirement. Kobach is leaving the secretary of state post because he’s running for governor (and facing a strong challenge from Democratic state Senator Laura Kelly, who backed his voter citizenship bill).

It’s hard to imagine a sharper contrast to Kobach than Brian McClendon, the Democratic candidate to replace him. A former Google vice president who helped build Google Earth, McClendon is one of multiple Democrats running for secretary of state offices who have emphasized election cybersecurity. He’s also sketched out a less centralized version of the Kansas secretary of state’s office that focuses on voter access. “With appropriate leadership and support from the state, county elections staff are admirably effective at managing voting rolls,” he told the Topeka Capital-Journal in June. “And the office of the attorney general is better staffed and better qualified to handle law enforcement and prosecutions in the rare instances of voter fraud.”

Not every Republican secretary of state has tried to suppress voter participation, and not every Democratic candidate will have the power to carry out sweeping changes if they win next month. Some races, in fact, are referendums on expanding voter access rather than suppressing it: Michigan’s secretary of state contest is taking place alongside a major ballot initiative that would enact automatic voter registration, Election Day registration, no-excuse absentee ballots, and a slate of other reforms. Jocelyn Benson, the Democratic candidate, supports the initiative, while her Republican opponent Mary Treder Lang does not.

Secretary of state contests haven’t always been high profile or high stakes. But as the Supreme Court abandons its role as a guardian of voting rights, and the Trump administration ramps up its efforts to combat the illusory threat of voter fraud, this once-esoteric position could be a key bulwark in protecting Americans’ right to choose their own political destiny.

No comments :

Post a Comment