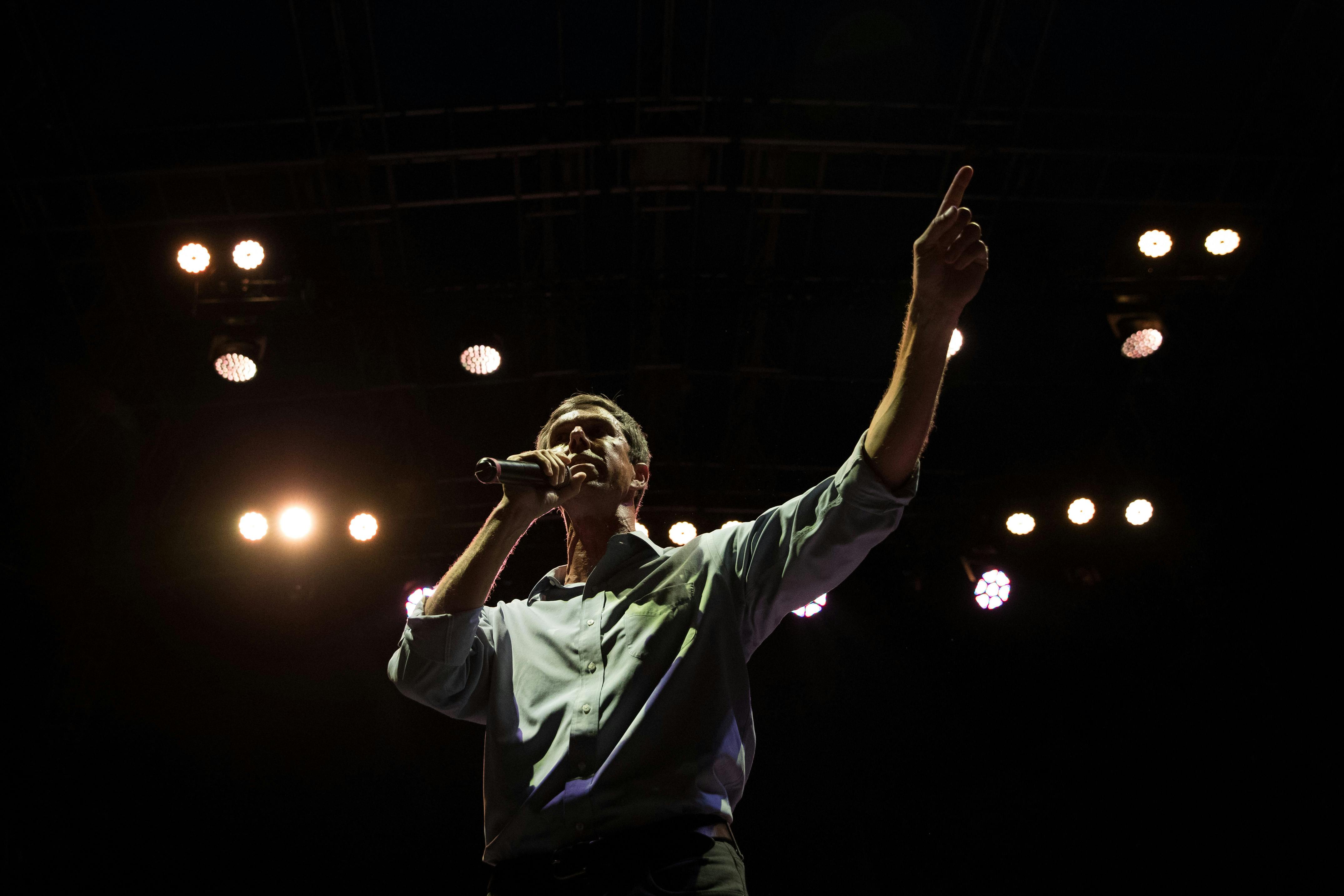

Beto O’Rourke, the three-term congressman from El Paso trying to unseat Texas Senator Ted Cruz in next month’s midterms, may be the Democrats’ biggest rising star since Barack Obama. Over the last few months, he has gone viral in defending NFL players’ right to protest during the national anthem and air-drumming to The Who’s “Baba O’Riley.” He has broken fundraising records, raking in $38 million for his campaign against Cruz in only three months. Just about every national publication has devoted page upon page to profiling his quixotic quest to turn Texas—Texas!—blue. He even skateboarded on stage without looking like a complete dork.

But with just over two weeks to go until the election, O’Rourke’s momentum seems to have fizzled—in Texas, at least. After appearing to be within spitting distance (in a few polls, at least) earlier in the campaign, O’Rourke has consistently trailed Cruz by between seven and ten points in recent days. That outperforms Cruz’s last opponent, then-Congressman Paul Sadler, who lost by 16 points in 2012, but not by as much as you would expect, given O’Rourke’s fame.

But in recent weeks, it’s become increasingly clear that O’Rourke has a back-up plan: the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination. From his discussions about “inspiration” and American greatness to his fierce rhetoric on climate change, O’Rourke is aiming at a national audience. While he’s certainly to the right of, say Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, he’s unabashedly liberal in a state where Democrats are typically conservative. O’Rourke—much like, it should be said, Cruz—is running for two races simultaneously, senator and president.

O’Rourke’s national appeal was to an extent strategic and to an extent inevitable. It was strategic insofar as Texas is a very large state and therefore a very expensive one in which to run a statewide election. Democrats have lacked the stomach to invest heavily in smaller states they dream of converting, like Georgia, because so much of the political infrastructure candidates need has to be built from scratch. Given Texas’ size and population, even if that infrastructure did exist, it would be expensive to run a competitive race in the state. But nationwide appeal means O’Rourke (like Cruz) has done very well from out-of-state donors (though it’s unclear how well).

At the same time, O’Rourke can thank his opponent for much of the prominence he’s gained over the last several months. Democrats have been dreaming of winning back Texas for decades, and O’Rourke is their best chance in a while. Cruz is not only one of the most prominent Republicans in America, but one of the most reviled men in politics. Given his prominence, his complicated relationship with Trump, and the threat of a “blue wave” in the November elections, Cruz was always going to attract a certain level of attention. The national media loves an upset, and O’Rourke unseating Cruz would be an even bigger shock than Ocasio-Cortez’s surprise defeat of establishment Democrat Joe Crowley. The national media also loves hip, handsome politicians, and O’Rourke’s boyish charm and optimism is all the more appealing when the foil is Cruz, “the Skeletor of American politics,” as Jack Shafer argued earlier this month (even if Cruz is just a year older).

With O’Rourke now a distinct long shot, the media has moved on to wondering if he will be a presidential candidate. In August, Vanity Fair said that O’Rourke’s campaign was a lot like being in Iowa with Obama in 2007. This is an act of journalistic hedging—it doesn’t make sense to deploy resources to extensively cover a guy who’s going to lose by ten points, but it does if he can be construed as a potential 2020 frontrunner. But O’Rourke has, particularly down the stretch, run a campaign as if his next stops were Iowa and New Hampshire, rather than the Senate. At his recent debate against Cruz, O’Rourke pontificated about “walls, Muslim bans, the press as the enemies of the people, taking kids away from their parents” and America’s place in the world. These are things that matter in Texas more than many other places, to be sure. But this is also what one expects to hear at state fairs and town halls in states with early primaries and caucuses.

O’Rourke has downplayed the 2020 talk, saying that his focus on national issues (and the president) is just him keeping it real—something that Democrats in Texas just don’t do. “Democrats in Texas have been losing statewide elections for Senate for 30 years,” he told Vanity Fair in August. “So you can keep doing the same things, talk to the same consultants, run the same polls, focus-group drive the message. Or you can run like you’ve got nothing to lose. That’s what my wife, Amy, and I decided at the outset. What do we have to lose? Let’s do this the right way, the way that feels good to us. We don’t have a pollster. Let’s talk about the things that are important to us, regardless of how they poll. Let’s not even know how they poll.” Of course, running on authenticity is exactly how a consultant would tell you to run against the ever-calculating Cruz.

If O’Rourke’s bid somehow succeeds, he would immediately become a frontrunner—maybe, with the possibility of a blue Texas, the frontrunner. (The polls says he’s also a top ten contender.) But O’Rourke’s fate, two weeks out, seems close to sealed: Even $38 million only goes so far. It’s also unlikely that if O’Rourke gets walloped, he’ll be able to carry the same swagger into Iowa and New Hampshire. Missouri’s Jason Kander won over a lot of nationwide Democrats with his losing Senate bid in 2016. He’s been able to parlay that into a national profile, but isn’t exactly being whispered about as a presidential candidate.

But however this plays out, O’Rourke has already accomplished a lot: He has shown Democrats how to run brave, uncompromised campaigns in the Trump era. As The Ringer’s Justin Charity wrote earlier this week, O’Rourke’s supporters “have come to regard his campaign as a quixotic candidacy: doomed but nonetheless hopeful, if only because O’Rourke has run so shamelessly through Texas as a true-blue liberal.” This is what the Democratic base wants out of the 2020 primary—especially with well-heeled centrists like Michael Bloomberg and Howard Schultz kicking the tires. And O’Rourke isn’t just running the kind of campaign Democrats in Texas want to see. He’s running the kind of campaign Democrats around the country want to see.

Ayanna Pressley’s surprise primary win over Michael Capuano—a power in Boston politics, with 20 years in Congress representing the Massachusetts 7th and the support of virtually the entire state Democratic establishment—defies easy explanation. Unlike other insurgent leftists who have roiled the political landscape this campaign season, she had trouble outflanking Capuano, a stalwart liberal who supported Medicare for All well before it was popular, from the left. But she did have some advantages. She’s young—44 years old to his 66. She is black and he is white, a decisive factor in a district that had become majority-minority in the decades Capuano has served in Congress. Most important, she was something new, and something new seems very much to be what voters want. Pressley packed her message of transformation into a three-word slogan that captured the urgency and promise of the first campaign season of the Trump era: “Change can’t wait.”

If Democratic leaders in Congress have given the impression that they are clueless riders on the tiger of an inflamed Democratic base—consider their tepid slogans “A Better Deal” and “For the People”—here was the tiger itself, muscular and immediate. The national press seized on Pressley’s slogan as a kind of mantra for a new political generation. CNN declared that it “connected the Democratic optimism of the early Barack Obama years to the urgency of Donald Trump’s presidency.” The network was right; Pressley was clearly paying homage to the last great Democratic slogan, Obama’s “Change we can believe in.” But even as she was harnessing Obama’s rhetorical prowess to target his poisonous successor in the White House, she was also making a critique of Obama and his legacy, and of the party he left behind.

The Obama presidency was indeed a source of inspiration for African Americans—“an eight-year showcase of a healthy and successful black family spanning three generations, with two dogs to boot,” as Ta-Nehisi Coates put it—but it was also a source of frustration. The pace of change was too slow, and Obama’s temperament too unflappable in the face of widespread social injustice. He was caught between suspicious white voters on the right and the enormous expectations of black voters (and white liberals) on the left, which limited his ability to address the issues of race head on. His famously artful response to the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012—“If I had a son, he’d look like Trayvon”—was a case in point: a constrained attempt at catharsis.

Ayanna Pressley unwraps a gift from a supporter with her slogan in needlepoint in Boston, Aug. 26, 2018. Kayana Szymczak/The New York Times/Redux

Ayanna Pressley unwraps a gift from a supporter with her slogan in needlepoint in Boston, Aug. 26, 2018. Kayana Szymczak/The New York Times/ReduxThose frustrations extended to Obama’s steady, deliberate approach to issues beyond race: stagnant wages, student debt, sexism in the workplace (and now, the White House), a broken health care system, a broken immigration system, and the yawning divide between the rich and everyone else. For many Democrats, these issues require more daring policies—Medicare for All, the abolition of ICE—than what Obama was willing to offer. They will also require a fundamentally different kind of politician. “Those closest to the pain should be closest to the power,” Pressley would say during her campaign—another striking line that, like her slogan, is sure to make certain Democrats wince, as it implicitly pits groups (minorities, working people) against others (whites, the wealthy).

But the real downside to Pressley’s slogan lies not in its class and identity politics, but in its unapologetic impatience. Democrats like Pressley want not just to send Donald Trump back to the world of reality television, but also to right the nation’s long history of wrongs with a dramatic flurry of legislative action. If, as many expect, Democrats take back the House in 2018, they will still be in a very rowdy minority, since any bill they pass will meet opposition from the Republicans in the Senate and the White House. The real challenge will come if Democrats are able to build off that success to win back control of the entire federal government in 2020. Then, there will be pressure from Democrats like Pressley to repudiate Obama’s measured style, as well as his repeated deference to the ghost of a bipartisan consensus that had all but vanished by the time he reached office.

Can this new kind of Democrat be realistic about the pace of change in a divided country, and, for that matter, in a divided party? Can the party move at a blistering pace without falling apart? That remains to be seen. Campaigns, of course, are not a time for realism but for expressing hopes and dreams, anger and frustration. In this respect, today’s insurgent Democrats are not all that different from those who, back in 2008, believed that change couldn’t come soon enough, who were themselves clawing their way out of the political wilderness, and who were encapsulated in another, similarly determined Obama slogan: Yes, we can.

Until this week, Jair Bolsonaro, the retired army captain leading the race for the Brazilian presidency, seemed like he would cruise to an easy win over his opponent, Fernando Haddad of the Workers’ Party (PT). Bolsonaro’s free-market proposals, including mass privatizations of state enterprises, appeal to investors. His attacks on human rights and due process, on the other hand, have alarmed others. Recent polls showed Bolsonaro with a double-digit advantage over Haddad ahead of election day on October 28.

Bolsonaro’s support—which has only grown despite homophobic remarks and open nostalgia for Brazil’s twenty-one-year military dictatorship—rests primarily on rabid anti-PT sentiment. Resentment of the country’s most popular party, marred by scandal in the past decade, has been diligently stoked through Facebook, Twitter, and, most prominently, WhatsApp, the free messaging service owned by Facebook. Indeed, WhatsApp, which is enormously popular in Brazil, has been the main driver of Bolsonaro’s histrionic campaign. Images that a sophisticated eye might clearly identify as having been doctored circulate freely among Bolsonaro supporters, reinforcing a visceral hatred of the PT and underscoring Bolsonaro’s image as a stern but honest alternative. One crude photoshop job shows the cover of a book written by Haddad, followed by pages wherein he appears to a defend incest, and call for murdering opponents.

For Bolsonaro, the allegations could be crippling. His appeal rests on his supposed incorruptibility.Now, it seems that aspects of the social media campaign may in fact have been illegal. On October 18, the newspaper Folha de São Paulo reported that during the campaign, private companies have spent $12 millions reais ($3.2 million U.S.) to disseminate hundreds of millions of anti-PT messages through WhatsApp. Amounting to an undisclosed donation to Bolsonaro’s campaign, such spending would have violated Brazilian electoral law. Bolsonaro so far hasn’t denied the allegations. Instead, he’s described the measures as entirely voluntary and unconnected to his campaign, although one witness described Bolsonaro asking explicitly for such support at a dinner with wealthy followers. Meanwhile Luciano Hang, a vocal Bolsonaro supporter who owns a chain of department stores, said that paying to inflate posts across social media networks would have been redundant. As he told Folha: “I just did a [Facebook] live here and it’s already reached 1.3 million people. Why would I need to [pay to] spread it?” On Thursday afternoon, Bolsonaro tweeted that the PT simply did not grasp that people would take such steps to voluntarily support his campaign.

For Bolsonaro, the allegations could be crippling. His appeal rests on his supposed incorruptibility—his purported rejection of under-handed means to secure political power, which he alleges is common practice for the PT. The PT won the last four presidential elections only to see its most recent standard-bearer, Dilma Rousseff, impeached in 2016 on charges of financial mismanagement.

Yet a great many Bolsonaro

supporters have embraced the radical right-wing congressman, who has served in

the legislature without distinction for almost three decades, with a zeal

bordering on the fanatical. They may accuse the media of conspiring against

their candidate, perhaps with the intention of shoring up Fernando Haddad.

Contextual evidence should make this narrative implausible: Haddad is no media darling. He has campaigned on diversifying Brazil’s notoriously oligarchical media landscape and his party is universally reviled in the editorials of mainstream publications. The notion that Folha would concoct this story only to favor Haddad may prove too far-fetched for some Bolsonaro supporters. This does not necessarily mean that they will reconsider their support for Bolsonaro, but it may lead to an acknowledgment that their candidate is not a squeaky-clean paragon of morality, a concession to reality that would improve the current political debate in Brazil.

For his part, Fernando Haddad, who has spent weeks publicly wondering who was financing the successive waves of fake news against him, has pounced on the allegations. Along with the Democratic Labor Party (PDT) of Ciro Gomes, who finished third in the first round of voting, Haddad’s party has filed charges with the Superior Electoral Court to annul Bolsonaro’s candidacy.

It remains unclear how quickly Brazil’s highest court for electoral matters will move to address the explosive findings. Brazil is hardly the only country at present where the role of online networks in extreme right-wing candidates’ campaigns has come under scrutiny. But in a country already polarized between those who oppose granting any quarter to far-right extremists and those who abhor the PT, tensions will almost certainly climb even higher with this new report. The revelations offer a distant hope for anyone concerned about an extremist like Bolsonaro taking command of the largest Latin American nation, and the ninth largest economy in the world. Only ten days until the vote, it’s possible not much will change. But there is now a sliver of a chance that Bolsonaro’s march to the presidency might be arrested, undone by a giddy reliance on the electoral potential of social media.

It’s been a year since the New York Times and New Yorker published their bombshell articles outlining how Harvey Weinstein had sexually harassed and assaulted women for three decades. Since then, the #MeToo movement has turned millions of women into the streets, toppled prominent men in Hollywood, media, politics, and Silicon Valley, and sparked a long overdue discussion about sexual abuse, especially in the workplace.

Meanwhile, the Democrats have moved left on issues from the minimum wage to college tuition, health care, and job guarantees. But perhaps surprisingly, there has been no such shift toward expanding the social safety net for victims of sexual harassment or domestic abuse. Some Democratic candidates have been discussing #MeToo on the campaign trail: In Texas, House candidate MJ Hegar revealed that she was a survivor of domestic violence in her viral campaign ad “Doors”; Anna Eskamani, who is running for a seat in Florida’s state house, spoke about being sexually harassed in her workplace; and Rachel Crooks won a seat in the Ohio state legislature in May after she publicly accused Donald Trump of forcibly kissing her in an elevator in 2005. But discussions of what they would do, if elected, to change workplace and domestic abuse policies for the better are less common.

One of these solutions is simple: paid sick and safe days for survivors of domestic abuse. The policy has been around since 2005, and in other countries, it has been growing increasingly popular. Over the summer, New Zealand passed a law that grants ten days paid leave to survivors of domestic violence—time to flee their abuser and find housing, medical care, and legal assistance. Some states have passed similar laws. Currently, 33 provide some type of unemployment assistance to victims of domestic or sexual abuse, and ten offer mandatory paid sick days. “It’s spreading like wildfire,” said Marium Durrani, a senior policy attorney at the National Network to End Domestic Violence. “A lot more are following suit.”

There are prototypes of federal bills making their way through Congress now, but they’ve been mired in congressional gridlock. Last November, a month after the Weinstein allegations broke, Washington Senator Patty Murray reintroduced her Security and Financial Empowerment (SAFE) Act to Congress. If passed, it would allow survivors to take up to 30 days off work to access the support they need, as well as protect victims from being fired if they are harassed at work. Meanwhile, a more general bill, The Healthy Families Act, would guarantee up to seven days of paid sick leave for all working families. Representative Rosa DeLauro introduced it in the House in March of last year.

These bills aren’t just good policy. They’re

good politics. With President Trump cutting already limited funds for survivors, they

would help Democrats draw contrasts between themselves and the administration. And

with the framework for paid sick days already in place in some states, the legislation could be easier to pass than other domestic violence bills—especially

if the Democrats, as expected, take back the House in November.

One in four women

in the United States face some form of domestic abuse in their lifetimes,

whether it’s physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual. This comes with an

economic cost. Abusers often delay or prevent their partners from getting

to work. “This is a classic example of power and control,” said Qudsia Raja,

the policy director at The National

Domestic Violence Hotline. The

abuser will “try to manipulate any form of support the survivor has, and

obviously your job is a big form of support.”

In other cases, women are harassed when they arrive at work—and when they report the abuse, according to a recent survey by the Maine Department of Labor, 60 percent either quit or are fired. In the United States alone, victims of abuse lose eight million paid days of work each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s roughly 32,000 full-time jobs that employers aren’t filling, creating an unpredictable workforce rife with absenteeism and employee turnover. Even when victims do turn up to work, they are less motivated and demoralized, which stunts their advancement.

But despite the magnitude of the problem, it’s hard to pass legislation that would help fix the issue. For one, domestic abuse has long been considered a private issue rather than a public one. It was only around 1994—when Congress finally passed the Violence Against Women Act, which marked the first comprehensive federal legislation protecting and preventing women from rape and battery—that domestic abuse was first considered a human rights issue, rather than something that happened in private, behind closed doors.

Still, domestic violence remains notoriously underreported. The Bureau of Justice Statistics had found that serious domestic violence was 31 percent more likely to go unreported to law enforcement for fear of reprisal—either from their partner, or on occasion, even from the government, which, in jurisdictions that have nuisance ordinances, actually punishes women who call 911 too many times.

From a legislative perspective, it’s hard to prevent women from being penalized for reporting abuse: Each state has different laws, and employers are given wide latitude to decide when and if to fire someone (domestic violence is not a protected class of employment, under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964), so if an abuser does call or turn up at the workplace of their victim and cause a disturbance, the employee is left vulnerable. And even if Congress were to pass a law to prohibit discrimination based on an abuser’s behavior towards a victim, how would they enforce it?

A policy that gives victims of domestic violence access to paid sick days, on the other hand, would be much easier to implement. Today, more than 40 percent of private sector workers in the United States have no access to paid sick days—a problem that persists because of aggressive business lobbing and the weakening of labor unions. Organizations like the National Federation of Independent Business and the Chamber of Commerce have consistently resisted paid leave policies, arguing that they’re expensive and that it should be left up to a company to decide how much is offered.

This means that women who are financially dependent are often trapped in abusive relationships because they can’t take the time off work to flee their abusers or pursue them in court. “If you miss your court hearing, then you don’t get your protective order,” said Durrani, who, before she joined the National Network to End Domestic Violence, was a lawyer representing victims of domestic violence in court. “Or you miss your job and your employer finds grounds to terminate you, and you probably don’t have resources to combat that. Beyond the physical and emotional implications of abuse, there are these long reaching ramifications.” Murray’s bill, and others like it, are a remedy for this.

One of the main conservative concerns about legislation like Murray’s SAFE Act is the cost: When a similar bill was introduced in Maryland, the National Federation of Independent Business, a conservative group funded by the Koch Brothers, argued that the legislation—The Healthy Working Family Act—could decrease output by over $1.5 billion by 2027. “This would lead to reduced profitability, lost sales and production, and lost jobs,” wrote Senior Data Analyst Michael Chow in a February 2017 report for the NFIB.

But that’s not the full story. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimated in 1995 that violence against women costs American companies $727.8 million in lost productivity each year—more than enough to make up the shortfall that Murray’s SAFE Act would produce. By allowing women to pursue safety without sacrificing a paycheck or their job, paid sick and safe days keep women in the workforce, which helps employers tap into a talent pool that is currently underused. Moreover, the Center for American Progress has found that when states passed similar paid family and medical leave laws, small business actually improved their profitability: their workers were more productive, their recruitment more effective, and their employees stayed at the company longer, too.

“We view this as making sure that workplaces implement policies so everyone can equally thrive,” said Sarah Gonzalez Bocinski, a program manager at Futures Without Violence, a nonprofit that works to end domestic and sexual violence. “Victims should not have to chose between job security and their own safety. It’s really a terrible choice that individuals have to make, especially for those in the lowest income jobs.”

For Democrats in Congress, aligning themselves with such legislation is smart from a strategic standpoint, as well. For one, it would help them set themselves apart from the president, who has not only stood by accused abusers but also ordered officers to reject the asylum applications of people who claim to be victims of domestic or gang violence. The bill also has the dual benefit of protecting both workers and businesses, at least in the long run. As the Democrats seek a message that sticks, these are just the kinds of policies they need more of, setting themselves up as the party of workers once more.

#MeToo “has created an opportunity where employers are reflecting on their own policies, particularly around sexual harassment,” Bocinski said. Now, it’s time for Democrats to “talk more broadly about a range of gender based violence and how [it] can manifest [itself] in the workplace.”

No comments :

Post a Comment