I wish John Roberts was right.

Last week, after President Trump denounced a federal judge who ruled against his administration’s asylum policy as an “Obama judge,” the Chief Justice replied with a ringing defense of judicial impartiality. “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges,” Roberts said. “What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them.”

What Roberts described is certainly the ideal. And it’s true that the courts are not rendering their decisions on legislators’ or presidents’ instructions. But in practice, many judges do end up ruling on the same partisan side as the presidents who select them. As our country has become more polarized, so has our federal judiciary. And that’s bad news for all of us.

The federal judiciary extends far beyond the Supreme Court to 94 district courts, the various lower appellate courts, and a series of more specialized courts. But while some of those appointments are less politicized than others, the example set by the Supreme Court has become hard to ignore. For the first time in our history, going by University of Michigan scholars Andrew Martin’s and Kevin Quinn’s quantitative estimates of judicial polarization, we have a Supreme Court where every Republican on the court is more conservative than every Democrat. Gone are figures like John Paul Stevens, a Republican judge nominated by a Republican president, who usually sided with Democrat-nominated justices on the court. To take another example, Lewis Powell was a conservative Democrat—chosen by Richard Nixon—who often joined the GOP wing of the court.

Nor do we have Anthony Kennedy, of course, who was replaced earlier this year by Brett Kavanaugh. Selected by Ronald Reagan, Kennedy joined Democratic colleagues in upholding abortion, gay rights, and affirmative action.

But Kennedy’s status as a “swing vote” was somewhat exaggerated, blinding us to the overall increase of polarization on the Supreme Court. In recent years, Kennedy joined the liberal wing in 5-4 decisions between a quarter and a third of the time. But in his final term, Kennedy stayed with his fellow conservatives on every 5-4 vote.

Meanwhile, the last two Supreme Court confirmations have proven beyond a reasonable doubt—as judges would say—that the Court has become a blatantly partisan institution. Although Republicans like to point to the failed Robert Bork nomination in 1987 as an example of extreme partisanship in the confirmation process, the truth is that seven justices since then have been confirmed with two-thirds majorities. In 2016, however, Republicans in the Senate blocked a vote on Merrick Garland, Barack Obama’s chosen replacement for the deceased Antonin Scalia. Then they rammed through a rule change to allow confirmation of justices by a straight Senate majority vote instead of the traditional 60-vote requirement, which allowed Trump nominee Neil Gorsuch to join the court in 2017 with only 54 senators supporting him.

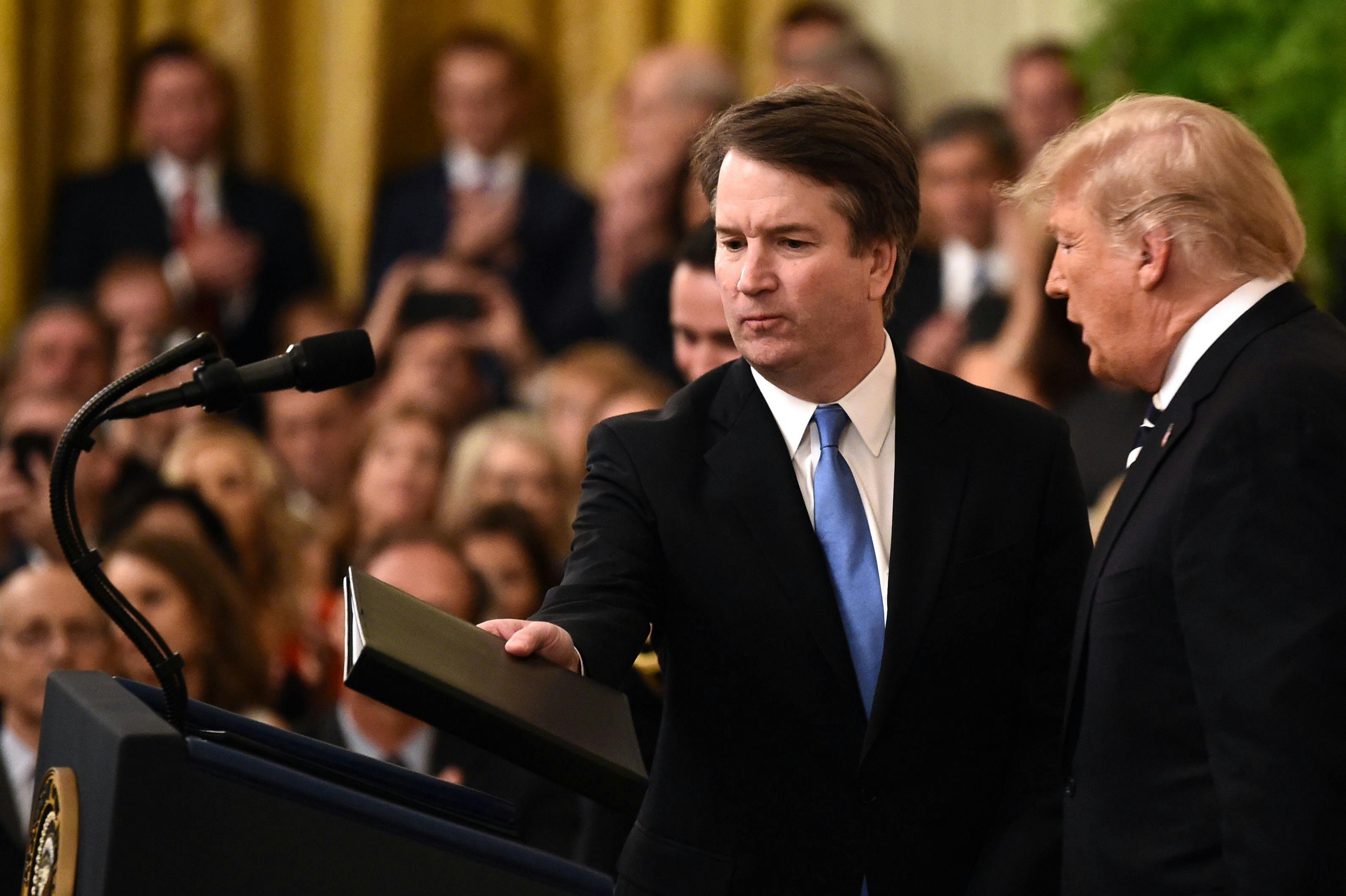

That was four more votes than Brett Kavanaugh received earlier this year, winning confirmation by the slimmest possible margin. In the first round of his Senate hearings, Kavanaugh tried gamely to present himself as an independent mind who operated above the partisan fray. Yet after Christine Blasey Ford leveled sexual assault charges against him, Kavanaugh went full-on right-wing conspiracy theorist: “This whole two-week effort has been a calculated and orchestrated political hit fueled with apparent pent-up anger about President Trump and the 2016 election, fear that has been unfairly stoked about my judicial record, revenge on behalf of the Clintons and millions of dollars in money from outside left-wing opposition groups,” Kavanaugh thundered at the Senate Judiciary Committee. “The consequences will be with us for decades.”

No matter what you think about Kavanaugh’s performance, he was right about the process. Unless we do something to change the way we appoint and confirm the federal judiciary, it will become exactly what John Roberts fears: just another weapon in our partisan, take-no-prisoners political culture.

We should start by restoring the 60-vote rule for Supreme Court confirmations, which would require presidents to nominate judges who could attract bipartisan support. Senate Democrats changed that rule in 2013, to ease the confirmation route for Obama’s lower court and Cabinet choices, but they retained the 60-vote threshold for Supreme Court nominees.

Then Senate Republicans applied it to the high court itself, which is the only reason Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh were able to join it. The best thing we could do right now is to go backwards, to the days when you needed more than a bare Senate majority to be on the Supreme Court.

We should also start identifying judges who could draw support from both parties, which is what many other democracies do. In Germany, where judges must be confirmed by a two-thirds vote of parliament, political parties negotiate over court nominees and come up with judges who can pass bipartisan muster.

Not surprisingly, between two-thirds and three-fourths of Germans express confidence in their highest court. By contrast, just 37 percent of Americans do. And even that number reflects a partisan split: whereas 44 percent of Republicans say they have strong confidence in the Supreme Court, only 33 percent of Democrats agree.

So here’s the challenge, for Americans of every political stripe: find judges from the other side of the aisle whom you could support, even if they wouldn’t be your first choice. We should demand that our Senators do the same. That way, the next time there’s a Supreme Court vacancy, we will already have a list of mutually acceptable candidates.

The alternative is a country of Obama judges and Trump judges, of Bush judges and Clinton judges. That’s Donald Trump’s nightmarish vision, of course, and John Roberts was right to criticize it. But we’re already living the nightmare when it comes to our federal courts. And only a renewed bipartisan spirit will jolt us out of it.

Did John Allen Chau, the Christian missionary killed two weeks ago by an indigenous tribe on a remote island in the Indian Ocean, deserve to die? There is the sense that, at the very least, the inhabitants of North Sentinel Island, part of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands located some 700 miles off India’s eastern coast, were justified in meeting Chau’s insistent proselytizing with a hail of arrows. “He invited that aggression,” an Indian anthropology professor told the AP. That so few have raised ethical concerns about Chau’s death makes this an extreme case, as if it lies outside any semblance of international law, in some space where only a blunt righteousness prevails—and it is this very quality, perhaps, that makes the story so compelling to audiences around the world.

Chau’s very presence on the island posed a danger to the Sentinelese, since they may not have developed immunity to the common microbes he carried with him. He also threatened their way of life: In recent years, given the growing consensus that modern visitors tend to erode the cultures of isolated tribes, the Indian navy has enforced a “no contact” policy with the Sentinelese and other tribes in the area, patrolling the waters to prevent infiltration by anthropologists and adventure-seekers alike.

The 27-year-old resident of Vancouver, Washington, possessed qualities of both: an ardent desire to make a connection across cultures; a taste for the dangers of rough travel (the bio on his Instagram account identifies him as “a snakebite survivor”). For all his wide-eyed eagerness, he bore a strain of old-fashioned Western superiority that can afflict both the social scientist and the avid tourist. As a child he found inspiration in Robinson Crusoe, while he and his brother would “paint our faces with wild blackberry juice and tramp through our backyard with bows and spears we created from sticks,” as he wrote in an online forum in 2014. Chau also idolized the Victorian explorer and colonist David Livingstone, of “Dr. Livingstone, I presume” fame.

Unlike an anthropologist, Chau was principally guided by religious faith, leading him to the conviction that the Sentinelese needed saving. Since 2015, he had visited the Andaman and Nicobar Islands at least four times, which heightened his obsession with the tribe. In the days before his final, fateful attempt to reach North Sentinel Island illegally on November 16, he was rebuffed in various ways, according to an extraordinary last letter he sent to his parents. He offered the tribesmen some fish, exclaiming, “My name is John, I love you and Jesus loves you,” only to be chased away with bows and arrows. He tried to sing to them, but was met with laughter. Another attempt to offer gifts resulted in a tribesman shooting an arrow straight through Chau’s waterproof Bible, the symbolism so on the nose that another person might have taken it for a sign from above. But Chau was undaunted: “You guys might think I’m crazy in all this,” he wrote to his parents. “But I think it’s worth it to declare Jesus to these people.”

Chau represented a very contemporary kind of villain: wholly oblivious of his ingrained prejudices, a menace in his smiling condescension. “Lord, is this island Satan’s last stronghold where none have heard or even had the chance to hear your name?” he wrote. A few fellow zealots have described him as a “martyr,” but scholars and pundits have recognized, tacitly or otherwise, that he was asking for something awful to happen. Even his parents seemed to acknowledge that his murder was his own doing, saying in a statement, “He ventured out on his own free will and his local contacts need not be persecuted for his own actions.” They added, “We forgive those reportedly responsible for his death.” There has been no serious attempt yet to hold anyone accountable. There are few hopes that Indian authorities will even recover Chau’s body, last seen being dragged, lifeless, across pristine white sands.

It is hard to imagine another scenario in which an American citizen could be killed with what appears to be total impunity—and not merely impunity, but with an accompanying notion that justice, however crudely, has been served. In other instances when Christian missionaries have plunged recklessly into hostile places like North Korea or the Taliban heartland, their frustrated governments have worked to secure their safety and release, under the legal and moral precepts that innocent people, no matter how misguided, should not be killed or jailed for attempting to spread their religious faith.

Chau’s case is different. It is basically a miracle that the Sentinelese, numbering as few as a few dozen people, continue to exist. Other indigenous tribes were wiped out when the British turned the Andaman and Nicobar Islands into a penal colony in the nineteenth century. Still others withered when they came into a more benign contact with anthropologists in the twentieth. It is no wonder the Sentinelese are wary of foreigners. For them to have successfully turned back yet another encroachment by the West, even in the figure of an irrepressible fool, seems like a rare victory amidst so much defeat. It feels like well-earned revenge.

A post shared by John Chau (@johnachau) on Jun 3, 2017 at 5:16pm PDT

But this is where the story’s underlying moral logic becomes almost too beguiling. Perhaps we want it to be that simple, for a man’s life to cost exactly that of a trespass of sacrosanct ground. Just as the Sentinelese appear to modern eyes to stand outside of time, with their rough-hewn weapons and ocean-bound lives, so does their rough administration of justice, suggesting some iron decree that is immemorial, nearing the divine: Cross this line and you will be struck down.

In much of the world, the rules that govern borders and sovereignty, that determine who can go where, are not so brightly defined. They are tacked together from a host of precedents and compromises, and riven with ambiguities and ethical pitfalls. Some people can cross, others cannot, and the difference is sometimes literally arbitrary, determined by lottery. There is nothing close to a consensus on what these rules should ultimately be, with the options ranging from walls to the abolition of borders altogether. At the root of this issue are fundamental questions about what it means to be a culture, a nation, a people. It is arguably the most divisive problem of our time, and easily one of the most explosive.

Just last week, as news was spreading of Chau’s death, no less a liberal eminence than Hillary Clinton declared that Europe “must send a very clear message—‘we are not going to be able to continue provide refuge and support’” to migrants. Clinton said this position was necessary because a flood of migrants to Europe, starting in 2015, had played into the hands of right-wing anti-immigration parties, feeding their popularity. The latter part of that statement is undoubtedly true, but critics pointed out that that is no reason to deny refuge entirely to those fleeing appalling conditions in their home countries.

There is no equivalence between Clinton’s callous remarks and the hostility of the Sentinelese—for one thing, the dynamics at play between the powerful and the vulnerable in these two situations are reversed. But the comparison reminds us that the world we live in is necessarily imperfect and often unjust, because its laws are the product of competing claims made in pluralistic societies. The fascination with Chau’s killing is multifaceted, but perhaps it is at least partly driven by the impossible fantasy of a world where solutions arrive with the directness of an arrow’s flight—and where justice and the law are one and the same.

No comments :

Post a Comment