Despite the Trump administration’s decision to release it on Black Friday, a new federal government report about climate change made headlines anyway. The 1,600-page Fourth National Climate Assessment, which details how global warming is already damaging the United States, got significant airtime on the prime-time cable news programs this Sunday.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that, during that airtime, non-experts made numerous false and misleading statements about the climate report and the scientists who wrote it. Those statements went largely unchallenged by the journalists in charge of gatekeeping the conversations.

It’s difficult to challenge falsehoods in real-time. But that’s why high-profile political journalists like Chuck Todd and George Stephanopoulos get paid the big bucks. Plus, the majority of falsehoods spread about climate change on Sunday’s news programs weren’t exactly new or novel. They were the same global warming talking points Republicans have been using for several years. They’re all easily refutable. There’s no reason why prominent political journalists shouldn’t be able to do it by now.

Take, for example, Iowa Senator Joni Ernst’s comments on CNN’s State of the Union. “We know that our climate is changing,” she said. “Our climate always changes, and we see those ebb and flows through time.” This is perhaps the most-repeated Republican climate change talking point in the history of Republican climate change talking points. Its sole purpose is to imply that the changes we’re seeing right now are normal—which is objectively untrue. Despite regional variations, the earth’s climate as a whole has been stable for the last 12,000 years. Now, all of a sudden, it’s warming more quickly than any time in the last 66 million years. What evidence does Senator Ernst have that this is merely a coincidence? Why didn’t the show’s host, Dana Bash, ask her?

Or take Danielle Pletka’s comments on NBC’s Meet the Press. Pletka is a foreign and defense policy expert at the conservative American Enterprise Institute—she’s “not a scientist,” she told Chuck Todd on Sunday. Because of that, she said she doesn’t know whether global warming is human-caused. But she does know this: “We just had two of the coldest years, biggest drop in global temperatures that we’ve had since the 1980s, the biggest in the last 100 years,” Pletka said. “We don’t talk about that, because it’s not part of the agenda.”

The global average temperature goes up and down every year, but the long-term trend shows rapid warming.NOAA.gov

The global average temperature goes up and down every year, but the long-term trend shows rapid warming.NOAA.govWrong. Scientists and journalists don’t talk about the last two years because short-term trends don’t matter when measuring long-term climactic changes. Republicans always talk about short-term, local records when they’re trying to refute climate science—it’s why Trump has been tweeting for years about cold temperatures during the winter. But when it comes to measuring climate change, all that matters is the long-term trend. And that long-term trend shows rapid warming.

Todd needed only to cite this simple description of climate science in order to fact-check Pletka on Sunday. To be sure, he could have said more—maybe that the only reason the last two years were so much colder than 2016 was because 2016 was the hottest year ever recorded, or that 2017 was still the third-hottest year on record. But none of that happened, and thus a woman who freely admitted she was not a scientist was allowed to spread pseudoscientific gobbledegook on the country’s highest-rating Sunday morning news show. (For what it’s worth, Republicans have also been spreading unscientific nonsense while claiming they’re “not scientists” for several years.)

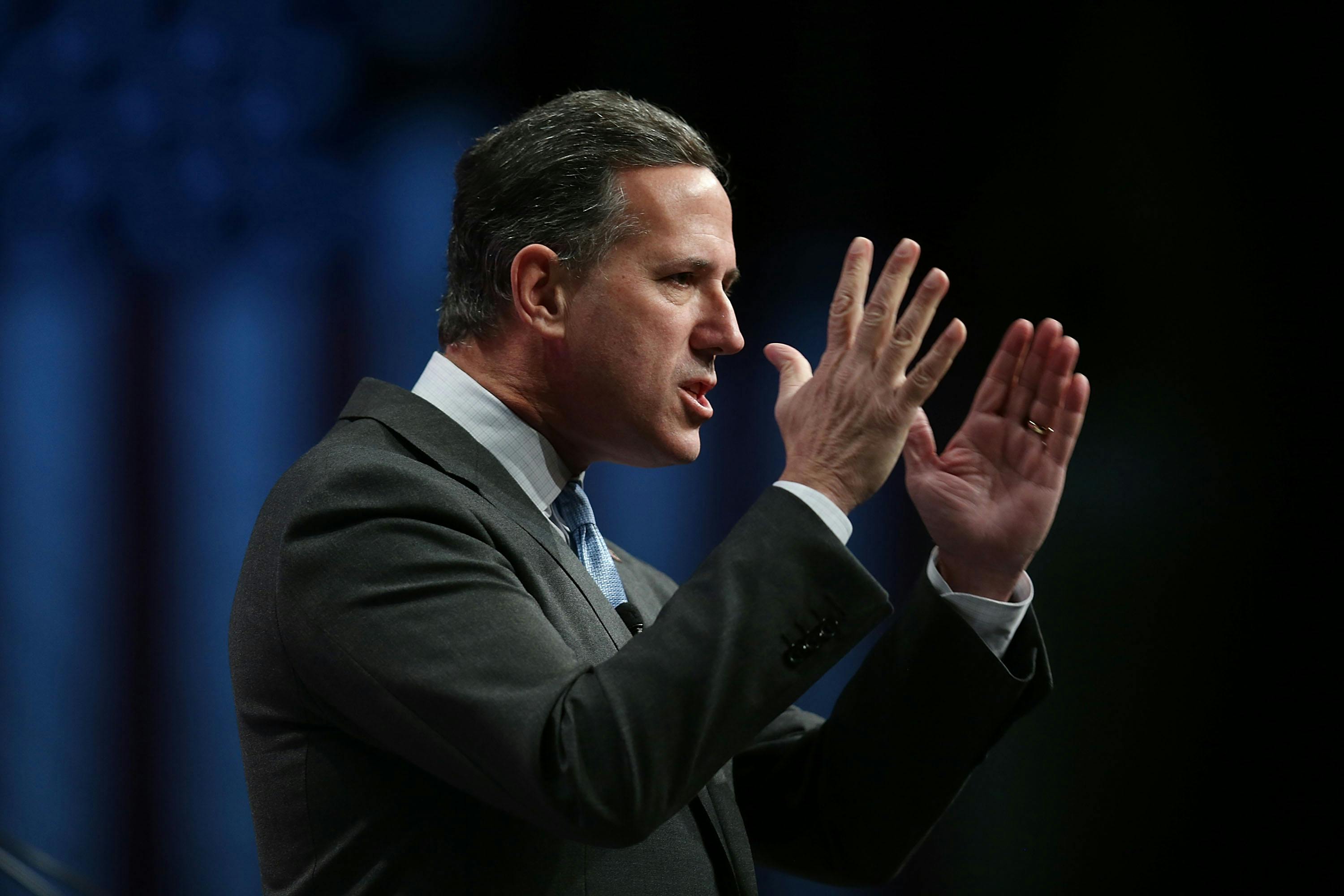

Pletka and others on Sunday also went unchallenged in spreading baseless conspiracy theories about the 300 federal government scientists who wrote the new climate report. Pletka did this by wholly rejecting their findings while subsequently citing “the agenda” to explain her reasoning. Twice-failed Republican presidential candidate Rick Santorum also accused scientists of having ulterior motives on CNN’s State Of The Union. “Look, if there was no climate change, we’d have a lot of scientists looking for work,” he said. “The reality is that a lot of these scientists are driven by the money that they receive.”

The idea that climate scientists need climate change to exist in order to get paid is an old talking point, and a false one. The climate affects every living thing on earth. “What happens when you emit a lot of carbon dioxide” isn’t the only thing climate scientists can, or do, study. Republicans who say climate scientists are getting rich off their research have never had evidence to support their claim. Their claim also strongly suggests they have never met any climate scientists, who as a group are hardly making global warming-related money hand over fist.

No one should feel comfortable making any of these baseless arguments on national televised news programs. But Republicans have learned over the years that they can—and that no one will refute them. Perhaps that’s because political journalists on television simply haven’t learned enough about climate change; they haven’t been covering it that often, after all. Fortunately, there’s a simple solution: If television hosts really can’t be bothered to read the latest climate science in order to moderate informed discussions, book more people who can. I, for one, am available all week.

In propounding one of his most intuitively appealing theories, Marx asked, “In what, then, consists the alienation of labor?” Alienation is the emotional state that takes place when capitalism divorces the worker from the product he creates. Because he does not “realize himself in his work,” the worker is only happy when he is not doing it: “He feels at home when he is not working, and when he is working he does not feel at home.” This is obvious, for Marx, because nobody works when they don’t have to. It is what makes working under capitalism a kind of forced labor.

Alienation is the chief theme in Heike Geissler’s 2014 book Seasonal Associate, published in the U.S. for the first time this December. The narrator, who is not named but strongly resembles Geissler, is a freelance writer and translator who has fallen on hard times (surprise, surprise). Squeezed by her financial precarity—she has children and debt—the narrator applies for a temporary job in an Amazon warehouse in Leipzig. She approaches her interview with a grinning resistance, disobeying a wall sign’s command to use the handrail by the stairs, for example.

SEASONAL ASSOCIATE by Heike Geissler.Semiotext(e) / Native Agents, 240pp., $13.99

SEASONAL ASSOCIATE by Heike Geissler.Semiotext(e) / Native Agents, 240pp., $13.99That meager dose of autonomy dissolves once she gets the job. The book is written mostly in the second person, with our unnamed narrator addressing somebody as “you.” The “you” is ostensibly her former self, the worker-self who is in the Amazon warehouse, as opposed to the writer-self, who is “real,” looking back on these strange events. At the start of the worker-self’s ordeal, the writer-self explains that, actually, you need this job. “You instantly grow ancient and wooden” at this revelation. From this moment on, you are “beside yourself with worry,” and the anxiety never abates.

Embedded into the very narrative structure of Seasonal Associate is Geissler’s awareness that the laborer under capitalism, bereft of control, splits into multiple selves who are alienated from each other. Who is the “I” who works for Amazon, and why is she so quiet? Geissler presses down hard on the identity changes that take place inside the worker who does not see herself in her work, then sublimates that analysis into the texture of her account.

This literary-political hyperawareness might sound intrusive or unhelpfully cerebral, but it actually reads as consolation. Geissler also scatters her book with meditations on work from Gertrude Stein, Eva Meyer, Monica de la Torre. There is an economy to being a person, de la Torre writes in her poem $6.82:

My economy is broken, mispronounced.

My economy has cold feet, even if there are plenty of socks at home.

My economy would like to be wholesome and sound.

My economy is a gift certificate that is not enough for what I’d like to have,

so I end up spending money at a store that I dislike in the first place and

will never visit again.

When the writer-self quotes lines from smart people who have also tried to understand how work and money affect the human experience, it is as if she is trying to soothe the Amazon-worker-self with memories of the other part of her brain, which still survives, though starved of oxygen. This all feels so terrible, she seems to say, but it doesn’t mean you’re not a writer.

The working conditions do sound terrible, unrelentingly so. The protagonist works beside a door that will not shut, allowing a draft that causes her to become and remain sick. The workers are supposed to be organized according to a nonhierarchical, horizontal structure, but in fact she is browbeaten and harassed by odious male colleagues. Her hands become chapped and remind her of her father’s hands.

Meanwhile the work—the work itself, not the conditions—grows absurd to a point beyond alienation, a point beyond language. “You come across a glass bathroom duck with a barcode not recognized by the computer. A new product, says Norman.” (The writer-self uses a lot of names for the other workers—Hans-Peter, Miriam, Uwe—but none for “you.”) The wayward duck must be addressed. “You take a closer look as you’re carrying it across the hall, barely noticing the floor markings. You’re carrying a glass bathtub duck; neither you nor I can say anything else about that.”

The unspeakability of the bathroom duck expresses two things. First, that any scenario that is sufficiently absurd can become funny in recollection, even if it was pure suffering at the time. Second, that language has become incommensurable with the Amazon-worker’s experience, because she is engaged in a kind of labor so alienated from ordinary existence that it cannot really be described.

Seasonal Associate makes working in an Amazon warehouse sound exactly as unpleasant as it is. As New York City reels from the news that the corporation will be taking up residence in Queens, and as protests by Amazon workers disrupted Black Friday across Europe, America’s culture of instant consumerism is being forced, at last, to confront the fact that this labor is done by people. We hear “fulfillment center” and we think of automation, of labor-saving systems that might reduce human alienation rather than enhance it. But this impression is a false one, and Seasonal Associate drives home this message with startling abruptness.

“We won’t be leaving this book before you’ve taken action,” the writer-self says. “I’m not sure. Have you taken action or not? Yes, you have. We’ll see.” Who is speaking here? We do not know: The writer and the worker inside Heike Geissler seem to come together at moments when action is demanded; the two identities become fluid, uncertain. The unasked question seems to be whether writing a book constitutes political resistance against this corporate behemoth, or whether anything can be said to be “done” until citizens show up in support of Amazon’s workers.

In Seasonal Associate, Geissler finds the absolute limit of writing about labor, at the very moment that history seems to have hit the same point. The “you” of Seasonal Associate is also, of course, the reader: This book is required reading for any consumer with a conscience. You won’t leave it without taking action.

At the end of If Beale Street Could Talk, Barry Jenkins’s film adaptation of the James Baldwin novel of the same name, the main characters, Tish and Fonny, sit with their son in the visiting room of the prison where Fonny has been incarcerated for several years. As their voices fade and their conversation becomes harder to make out, a weary rendition of “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” begins to play and the credits roll. The takeaway here—unsubtle but still provocative—is that for black families, burdened by the injustices of the U.S. legal system, citizenship is both a birthright and a plight. How can we feel at ease in a home that is also a torture chamber?

That is where Jenkins leaves us, but it is not the complete expression of where he wants us to go. This is his third feature-length film, and at the center of each of them is a love story. His first, 2008’s Medicine for Melancholy, is a romantic drama about an extended one-night stand between two black hipsters in a gentrifying San Francisco. Micah (Wyatt Cenac) and Jo (Tracey Heggins) hook up at a party without getting each other’s names. They spend the next day exploring the city they love, whose changes they are witnessing as young adults. Their differing views on the politics of blackness (Micah is race-conscious and activist-minded, whereas Jo prefers not to define herself solely through the lens of blackness), as well as Jo’s existing relationship, threaten to derail whatever chemistry they have.

Jenkins’s second film turned him into a star. Moonlight famously and infamously won the Oscar for Best Picture in 2017, though the Hollywood musical La La Land was originally announced as the winner during the broadcast. (Jenkins also picked up an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay, co-written with Tarell Alvin McCraney, on whose play the script is based.) Moonlight is a triptych coming-of-age story about a young black Miami native named Chiron, alternatively called Little and Black at different points of his life. He grows up with a crack-addicted mother and adopts her dealer as a father figure. He is also relentlessly teased by other children for his imagined homosexuality. As a teenager, he has a single sexual experience with his only real friend, but the two young men drift apart as their lives go on to be defined by violence, prison, and the ongoing illegal drug trade.

Both Moonlight and Medicine concern black people trying to find pathways toward love that will sustain them through the hardships of their black American experience. In If Beale Street Could Talk, too, Tish (KiKi Layne) and Fonny (Stephan James) live a version of this, facing separation when Fonny is imprisoned just as Tish learns she is pregnant. It has taken until now for a filmmaker to adapt Baldwin’s 1974 novel—in part because his family has closely guarded the legendary author’s estate—but Jenkins shows a particular affinity for his work. A preoccupation with love, and more specifically with the ways black people find to express love among themselves, connects him and Baldwin. Neither is totally convinced that love is what will save us, but they still believe in its transformative potential.

Even for Jenkins, riding high from the success of Moonlight, If Beale Street Could Talk was a formidable undertaking. Baldwin was a prophetic writer—the poet and playwright Amiri Baraka called him “God’s black revolutionary mouth.” His critiques of American racism still stand today, and have influenced subsequent generations of black writers, from Ta-Nehisi Coates—who famously modeled his blockbuster memoir, Between the World and Me, after Baldwin’s essay “My Dungeon Shook”—to the writers in Jesmyn Ward’s anthology The Fire This Time. To bring one of his novels to the screen is to engage with the artistry and force of a whole tradition.

In the 2016 documentary I Am Not Your Negro, which was based on Baldwin’s unpublished memoir Remember This House, Raoul Peck made the language the focus of his film—pairing Samuel L. Jackson’s voice-over with imagery that matched the intensity of the critique. And, though Peck’s film was nonfiction and Jenkins’s is a drama, Jenkins’s instinct, too, has been to lean on Baldwin’s words. Tish, who is the narrator in the novel, also narrates here through voice-over. Her story begins in prison, where she is visiting Fonny to bring him the news that they are expecting a child together. Fonny is elated, despite his circumstances—he has been accused of raping a Puerto Rican woman, and while he maintains his innocence, the legal system, aided by a racist white police officer, seems intent on keeping him locked away.

This part of the story is difficult territory, especially in our current cultural environment. There is a history of false rape accusations against black men, which have largely been used as pretext for lynchings. This was a grave concern during Baldwin’s era, and though it is not as much today, we still live in a world in which such accusations persist: In October, a white woman in Brooklyn claimed that a nine-year-old black boy sexually assaulted her, after his backpack brushed against her in a crowded deli. At the same time, the #MeToo movement is emphasizing the importance of listening to women’s stories of rape, assault, and harassment, and taking those stories seriously. A plot centering on a false accusation could cut against the principle of believing women. The danger in adapting this story would be to ask which group is more credible, whose historical mistreatment deserves more weight.

Beale Street, though, is not neatly enclosed in any binary. Baldwin’s novel takes care to give voice to Fonny’s accuser, Victoria Rogers, while also depicting Fonny’s own suffering—and Jenkins carries this nuance into his film. In one scene, Tish’s mother, Sharon (Regina King), has flown to Puerto Rico to try to convince Victoria (Emily Rios) to recant her accusation. “I was a woman before you got to be a woman. Remember that,” Sharon tells Victoria, assuring her that she knows what it is to be violated in such a way, to feel men’s violence against her own body. But she cannot bring herself to believe that Fonny is capable of such an act, having known him since he was a child. In the book, Victoria has an eloquent and indignant response to that view:

Hah!… If you knew how many women I’ve heard say that. They didn’t see him—when I saw him—when he came to me! They never see that. Respectable women—like you!—they never see that.…You might have known a nice little boy, and he might be a nice man—with you! But you don’t know the man who did—who did—what he did to me!

In the film, she is quieter—she trembles as Sharon pleads but she doesn’t bow to pressure. She refuses to say she is lying or has been coerced into identifying Fonny. Jenkins tends to suggest that Fonny was set up, but his innocence is never made entirely clear.

It took a delicate hand to ensure these somewhat competing truths did not break the narrative apart. But there’s something else that guides Jenkins, generally and more acutely with Beale Street: He provides space for his character’s flaws while never allowing those flaws to define them. He is not interested in exonerating them, but rather in indicting the world that makes love so difficult for them to attain.

In Moonlight, Chiron has been deemed wrong by his surroundings—he’s too feminine, too queer, too quiet to be accepted. The only one of his peers willing to speak to him in a way that is not demeaning is ultimately responsible for his tenderest adolescent moment and the most vicious violence he experiences. They are both trying to prove themselves hard enough to survive a time and place in which the touch they crave from each other is discouraged by an unrelenting homophobia.

Beale Street is, like Medicine for Melancholy, concerned with a more hetero love story, but it shares that sense of outside forces haunting young black people’s ability to hold onto each other’s love before something threatens to break them apart. Tish and Fonny never manage to buy their own home. After he’s sent to prison, Fonny’s best alibi, his friend Daniel (Brian Tyree Henry), is considered an untrustworthy witness because he himself just got out of prison after a wrongful conviction (which he details in the film’s most powerful scene). Fonny’s legal fees keep running higher and higher, causing the two lovers’ fathers to scheme on some illegal hustles to make certain they can continue to fight his case. All those involved find themselves in this predicament only because a racist police officer has made Fonny his personal enemy.

Everything is stacked against Tish and Fonny. His masculine pride doesn’t allow him to see how much she suffers alongside him, leading her to remind him, during one of her visits, that she, too, is going through this ordeal. In his book on film criticism, The Devil Finds Work, Baldwin writes, “The private life of a black woman ... cannot really be considered at all.… The situation of the black heroine ... must always be left at society’s mercy” for the sake of preserving white innocence. Though Baldwin identified this tendency, he never quite engages with it in his novel; Jenkins makes the choice to take Tish’s pain seriously.

What Jenkins does best—in a film dominated by Baldwin’s prose—is convey emotion through silence. The first time Tish and Fonny make love, they don’t speak to each other in the moments leading up to the act. Jenkins lingers on their bodies, Tish’s virginal vulnerability, Fonny’s tender knowing. They look into each other’s eyes, up close and from across the room—Jenkins’s languid camera movements from one to the other make it feel as if the audience is in between them. When Fonny undresses, his beauty is so distracting that you could miss that he’s almost as nervous as Tish, who can’t take her eyes off of him. He approaches her, and you can nearly feel their quick breaths on the back of your neck. By the time he is on top her, telling her that she will have to learn to trust him, you’re in love for them.

That’s precisely what Jenkins wants; this closeness makes it all the more devastating, later, when he has to break your heart.

Driving around the part of Fresno, California, where Shannon Brown spent much of her life feels a bit like entering an alternate, more insular version of America, something out of an earlier time. We passed a white woman holding a baby in a driveway. An older white man worked in his yard. A white woman walked a dog. There didn’t appear to be a single person of color in the area, I said. That’s because there are none, Brown replied.

Brown, 48, is white, with blond hair, pale blue eyes, and milky skin. She wore a checkered black-and-white dress, a silver cross dangling from her neck. Brown had nothing against diversity, she explained. She was just accustomed to living among people who look like her—it’s the way she was raised. When she was growing up, her family discouraged Brown from associating with those people. “They definitely did not like black people. We never had black people over,” Brown said. “My family wasn’t overtly racist,” she said, but they weren’t going to befriend nonwhite people or welcome them into their home. Her family members, like many residents of this part of Fresno, are “polite racists,” Brown said, the kind of people who smile to your face if you’re a minority and call you a racial slur behind your back.

White power organizations are not uncommon in California—the state actually has the most active hate groups in the nation, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center—but Brown’s family disapproved of their criminal behavior, if not their ideology. The racism that Brown grew up with was rooted in the belief, Brown said, that “We’re better than them.” They looked down on minorities but wouldn’t go so far as to use violence against them.

Still, for Brown, neo-Nazis were part of the social fabric of her California. They were her neighbors and acquaintances, people she would see from time to time, maybe even hang out with. One evening in 1996, when Brown was 26, she and a girlfriend from beauty school met up with a couple of guys they knew casually from around town. The four of them gathered at a local diner, and the men handed Brown and her friend blindfolds and invited them to get in their car. They were in the Ku Klux Klan, the men said, and they wanted to take Brown and her friend to a gathering at the secret “klavern,” a local KKK unit where the group held its meetings. This was new for Brown. “What’s a klavern?” she remembered asking. “We didn’t know what any of this stuff was.” But she liked hanging out with the guys, and she was intrigued, so she got in the car.

Brown remembered being driven around in what seemed like circles for a long time. “It’s a miracle we didn’t end up in an orchard dead somewhere,” she said. Finally they stopped, and the men led them into a house. Blindfolds removed, the women found themselves in a room of nearly two dozen skinheads, neo-Nazis, and men in white hoods, a mash-up of commingling white power factions. There was a pregnant woman in a grand robe, and a white power symbol was painted on the floor—a cross encircled in red. Brown wasn’t afraid or disgusted. Instead, she found it alluring and exciting.

As we drove around Fresno, Brown slowed to a stop in front of a pale-yellow one-story house adorned with yellow tulips, an American flag flapping on its solar-paneled roof. She pointed to the double-car garage. “That’s it,” Brown said. “That’s where the klavern used to be.

After that initial visit, Brown fell quickly and deeply into the KKK life. She started attending monthly gatherings at the house. Her family had always associated white power groups with criminality and violence, but Brown didn’t witness any of that. To her, it just meant belonging to a social circle of people who shared the same beliefs and values that she did. She even fell in love and married one of the men who first brought her to the klavern.

Together, Brown and her husband moved 125 miles south to Taft, California, near Bakersfield, a rural area, in a neighborhood far from any minorities. Her husband worked as a derrick hand on a drilling rig in the oil fields. He had two young kids from a previous relationship, and Brown helped raise them according to the hate group’s ideology, in a world where they performed the Nazi salute and sported t-shirts with slogans like the original boys n the hood. Children’s birthdays involved cakes decorated with swastikas and iron crosses. Watching television was rare, except for Little House on the Prairie.

Brown embraced the culture, abided by it. She was a housewife who quilted and cut hair. For fun, she practiced shooting guns, which were always around the house, with her family. At night, they occasionally attended cross burnings. She liked to listen to music from Johnny Rebel, a singer who rose to popularity among white supremacists in the 1960s and ’70s with songs like “In Coon Town” and “Ship Those N-----s Back.” In public, Brown was still a “polite racist” like the rest of her family in Fresno, but her husband, who proudly wore his white power tattoos, wouldn’t hesitate to verbally abuse minorities they encountered on the street—a habit that Brown said she found “embarrassing.” In private, however, racist views were expressed freely and openly. “Ring that bell, shout for joy, white man’s day is here,” Johnny Rebel sang on their stereo.

That life is all behind her now, Brown said. In 2000, she divorced her husband and cut ties with the Klan. Mainly, it was her husband’s abuse that prompted her to leave. He was violent and controlling, and she had tried escaping from him several times, but he tracked her down. Finally, she managed to get back to Fresno, where he hasn’t been able to locate her. If not for the abuse, Brown said, she probably would not have broken free from the Klan. “I left everything,” she said. “I basically had to start over.

For years, Brown didn’t talk much about her former life, and most people didn’t know about it—even her family wasn’t aware that she had joined the KKK. She found a job at a hair salon with diverse clients and staff, including African Americans, and she worried what they would think of her if they knew about the contempt for them she had harbored. She watched on the news as the same Klan members she’d once considered friends were arrested for hate crimes and unlawful possession of weapons, counting herself lucky not to be among them. And she has tried to atone for her racist past, speaking regularly to college classes and audiences at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles about her past experiences with the Klan.

Last year, Brown officially joined Life After Hate, a nonprofit organization founded by former white supremacists that works to help people leave extremist groups and start new lives. Groups such as Life After Hate have received increasing attention since Donald Trump’s election. Modeled after similar organizations in Sweden and Germany, they aim to teach tolerance and support former white supremacists in a kind of recovery process. “If you’re ready to leave hate and violence behind, we’re here to support you. No judgments, just help,” the Life After Hate web site declares. This involves breaking ties with hate group members, including loved ones, reintegrating into mainstream society, and trying to “unlearn” racism. Life After Hate received a $400,000 grant from the Obama administration to support its work—funding that the Trump administration stripped away in 2017.

“Even 20 years later,” Shannon Brown said, things still trigger her hateful thoughts—black people, gay people, multiracial families. “It sounds terrible to say, but it feels good.”The goal of stopping hate and helping former white supremacists lead more virtuous lives is certainly well intentioned, but there is reason to doubt the effectiveness of any initiative’s methods to reverse racism. Life After Hate, which formed as a nonprofit in 2011 and claims more than 30,000 supporters, says it has helped more than 100 people conquer their biases. Ending racism, it turns out, isn’t as simple as cutting personal ties or deciding to stop hating certain groups of people.

Shannon Brown, for example, admits that there are still things that “trigger” her prejudices: gay people, black people who listen to loud rap music, multiracial families. Something might set her off, and “I just trigger into that indoctrinated kind of mindset,” Brown said, her brain calling forth a racial slur, even though she knows that such thoughts are wrong. “I might just see something like an interracial couple, and it’ll flip and then flip back real fast,” Brown said. “Sometimes I can control it, and sometimes it’s just on impulse.

Hate is a powerful emotion that lodges itself deep within a person’s psyche. Indeed, a growing body of social, psychological, and neurological research suggests that once racial biases and hateful ideologies embed themselves in a person’s brain, they can be difficult—if not impossible—to counteract. This research suggests an uncomfortable reality: that ending racism isn’t something that can be achieved through a handful of counseling or therapy sessions, or anti-bias training. In addition to the efforts of organizations like Life After Hate, millions of dollars have been spent in recent years on high-profile anti-bias initiatives at companies including Starbucks, Facebook, and Google, as well as in police departments across the country. Yet there is little evidence that these efforts even work.

Spending time with Brown, I could sense her struggle to keep her biases in check. The Klan had taught her to despise any kind of racial mixing—particularly white people mixing with other races, which threatened the purity of the white race. When I told Brown that my husband is black, and so are my kids, she looked offended. Interracial relationships are still a significant trigger for her; the idea that it was forbidden to marry a black man was “pummeled into me,” she said. I could practically hear the Johnny Rebel lyrics echoing in her head. “Oh affirmative action, what’s this country coming to? Affirmative action, what’s the white man gonna do?”

I told Brown that I am also biracial; my mother is white. “I didn’t know you were mixed,” she said. “I assumed you were … you look Asian.”

“Does it matter?” I asked. Brown shook her head. “Just a surprise.” Outwardly, Brown kept her cool. But I imagined little pistons in her brain firing, synapses ablaze, racial epithets rushing to the tip of her tongue. Fighting the hatred inside her head can be exhausting, Brown said. Sometimes it’s just easier to let her old racist mindset reassert control. “Even 20 years later, it’ll flip the switch,” Brown said. “And it sounds terrible to say it, but it actually feels good.”

Scientists have been working for more than a century to understand how racism operates—and how it might be cured. The notion that biases can be identified and overcome connects with early theories about how racism manifests in the brain. From the 1920s to the 1950s, psychologists studying racism considered prejudice to be a psychopathology—“a dangerous aberration from normal thinking,” writes John Dovidio, a Yale University psychology professor, in the Journal of Social Issues. Psychologists employed personality tests to identify prejudiced people, with the hope of understanding how to treat them with psychotherapy, under the assumption that “if the problem, like a cancerous tumor, can be identified and removed or treated, the problem will be contained, and the rest of the system will be healthy.”

By the 1970s, however, psychologists had developed a new theory. An individual’s personality, character traits, and beliefs were predominantly influenced by the place in which she grew up and the people she was surrounded by—“nurture,” in other words, not “nature.” Racial prejudice was a societal ill, something learned through a lifetime of conditioning and exposure to hateful ideas—and therefore “normal”—and not a disorder that could be treated medically in any one individual.

Studies over the past two decades, however, have both clarified and complicated these ideas. Scientists now recognize that we are influenced by both our genes and our environments—the forces of nature and nurture work in tandem. On the one hand, stereotypes and prejudices are not innate. Racism is not simply an evolutionary reaction to an inherent human predisposition to be “tribal.” But there is a biological component to hatred and racism, which interacts with environmental factors. Studies show that growing up around people who espouse racist views—or even simply in an environment that lacks diversity—can contribute significantly to how a person interprets race.

“Our brains have evolved to be really sensitive to differences in our environments, to novel things,” said Jeni Kubota, a psychologist at the Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture at the University of Chicago. “Those systems, because of the culture, have co-opted the processing of race.” The brain categorizes people very quickly—friend or foe, threat or non-threat—based on information it has learned, and if the brain makes its assessment using biased information, the results will reflect that bias. “Unfortunately, that leads to horrible inaccuracies and in some cases life-and-death consequences,” Kubota said. “So the system that’s really efficient in processing a lot of information can also lead to a lot of harm.”

Studies show that racism is not simply an evolutionary reaction to an inherent human predisposition to be “tribal.” But there is a biological component to it.New technologies have helped scientists understand more fully how the brain processes race. Advanced MRI scans have revealed that a network of brain regions associated with decision-making and emotional responses come into play when people assess someone’s race. One key area is the amygdala, which plays a role in controlling emotions, fear, and survival instincts, like the fight-or-flight response. When triggered by something considered a threat, neurotransmitters like norepinephrine, adrenaline, and dopamine are released into the amygdala. This process kicks the body into alert to protect itself. In scientific studies, white people have displayed increased amygdala activation in response to seeing black faces. These findings suggest that the study participants had developed negative stereotypes about African Americans, and their brains therefore categorized black people as threatening.

Another region of the brain involved in the processing of race is the prefrontal cortex, often referred to as the seat of executive function. It is here that moral behavior is regulated and controlled. Individuals with damage to this region have experienced sudden, dramatic personality shifts, like the famous case of Phineas Gage, who was working on a railroad construction site in 1848 when there was an explosion. An iron rod rammed through the frontal lobe of his brain. Gage survived, but this previously polite man suddenly became crass, offensive, and rude. Individuals with neurodegenerative diseases that affect their prefrontal cortexes have also experienced stark shifts in moral behavior, including lewd sexual conduct, trespassing, assault, theft, and even sudden drug dealing.

These cases have helped scientists understand how essential the prefrontal cortex is in filtering our behavioral choices, like not walking around naked, or stealing, or fighting, or telling someone that he is ugly or dumb. Many of us move through the world at times experiencing socially inappropriate feelings or urges, but we control how we react to them. Our healthy prefrontal cortexes regulate potentially embarrassing actions based on our impulses.

Neuroscience shows that ordinary people “recruit these brain regions when they’re interacting with people of other races,” Kubota said, “particularly if they have a motivation to not be prejudicial.” Individuals who believe in equality and fairness, or who are aware of their own biases, she explained, seem to be exercising a kind of self-control, evident in the prefrontal cortex, over their behavior—keeping prejudicial associations in check when they are thinking about or interacting with people of different races.

Angela King, the co-founder of Life After Hate, grew up in South Florida and became involved with a gang of neo-Nazi skinheads when she was 15 years old. She inked white power tattoos all over her body—a swastika on her middle finger, SIEG HEIL on the inside of her bottom lip—and talked about race wars while spreading hate propaganda. In 1998, when King was 23, she and some friends robbed a Jewish-owned store and assaulted the clerk. Weeks later, she was arrested, and the following year she was sentenced to six years in prison.

One day, while smoking a cigarette with her back against a wall, King noticed a Jamaican woman eyeing her. King thought she was going to start a fight with her. Instead, the woman asked, “Do you know how to play cribbage?” The woman sat down next to King and taught her how to play the card game. King became friends with her, as well as her black friends. They questioned King about her beliefs while simultaneously showing her compassion and love. “They were treating me like a human being,” King said. “It blew me away, because I didn’t feel like I deserved it, and I wasn’t expecting it. To receive that, it’s not something that you can ask for or would even know to ask for. It’s a gift like forgiveness, that when you get it, it changes everything.”

King was released in 2001, after serving three years of her sentence. “I knew I still had more changing to do,” she said. “I knew that I wanted to be a different person, but I was absolutely horrified, because I was afraid that my brain was hardwired.” King had made friends across races. She had even fallen in love with a black woman in prison—finally accepting an aspect of her identity that she had hidden from her homophobic skinhead friends. Yet she still struggled to keep racist thoughts at bay. “No matter how many friends of color I made or how much interaction I had, I could see a person of color and my brain would automatically think a racial slur,” she said. “I was afraid that there was nothing that I could do myself to change it.”

She was determined, however, and kept working on it. After prison, King earned a degree from the University of Central Florida, where she studied psychology, anthropology, and sociology, and learned about white privilege. “I literally walked around for the first few years talking to myself,” she said. “If I thought a racial slur or homophobic slur or felt a fear that was irrational, anything, I would literally stop myself and say, ‘OK, Angela, why did you think that?’” King said she eventually got to a point where she “was finally unwinding all of the garbage” in her mind.

Studies show that motivation contributes to how successful a person will be at keeping their prejudices in check. According to Jeni Kubota, if you deeply feel, “I’m a person who believes in fairness and equity,” and “It’s part of who I am at my core,” this internal motivation can help lead you to eliminate biases. But if a person’s desire to not be prejudiced stems from the feeling that “other people tell me that’s bad,” Kubota said, those external motivations are not usually enough to curtail or control prejudice. Without that internal motivation driving them, even people who actively try to be less biased will most likely fail.

Prejudices and biases “are rooted in longstanding, chronic, perpetual processes within the culture,” said Calvin Lai, the director of research at Harvard’s Project Implicit lab, which studies bias. If an individual has grown up in a racist culture, fighting against that current of hatred requires enormous mental determination.

Beyond her internal motivation, King also benefited from something else: meaningful contact with people of other races. The close relationships King formed in prison weren’t just the catalyst that motivated her to renounce racism; they provided an essential foundation for the entire process. According to Kubota, contact with people of different races has been shown to reduce bias in the brain considerably—but that contact has to be significant. “It can’t just be ‘put us all together in a school and we segregate and never talk to each other,’” Kubota said. That can actually reinforce biases. But researchers have found that having meaningful friendships, beloved mentors, or bonds with different people over long periods of time “can diminish these differences we see in the brain based on race,” Kubota said.

Angela King started Life After Hate with other former white supremacists because she wanted people like herself to know that they were not alone, and to offer them resources to help reintegrate into mainstream society—counseling, job training, mentoring, and peer support. “A person may really be struggling with alcohol addiction, or they’re dealing with criminal charges, or any number of things. So when it’s possible, we will actually travel to people to do face-to-face interventions,” King said. “Other times, it’s done virtually—Skype, phone calls, social media, any way that we can connect with people.” All of these things can play an important role in helping people break away from hate groups and get their lives back on track. But that doesn’t mean they’ve rid themselves of racist beliefs. King recognizes that the powerful transformation she experienced cannot be replicated easily. You cannot manufacture meaningful experiences for others, and you cannot force someone else to feel a strong motivation to change.

The decision to leave a hate group is almost always driven by a personal stimulus—an abusive relationship, a run-in with the legal system—not by empathy for other people.“Approaching someone out of the blue and just trying to talk someone out of their beliefs is not successful,” King acknowledged. “People don’t want to hear that they’re racist. They don’t want to hear that they’re part of a racist system, and that they are complicit in what is happening to their fellow human beings.” As much as King believes in working to end racism, there are days when she feels like it is impossible. “I honestly don’t know how we move beyond this, especially as we progress with technology,” she said. “It is so easy for people to be so connected and disconnected at the same time.”

It would be nice to believe that people leave extremist groups because they suddenly realize that their views are ugly, hurtful, and prone to cause violence. However, according to research by Peter Simi, a sociologist at Chapman University in Orange County, California, most former white supremacists do not experience a sudden change of heart. In fact, moral reasons fall to the bottom of the list. Instead, as was the case with Shannon Brown, the decision to leave a hate group is almost always driven by a personal stimulus: a social or family feud, a divorce, an abusive relationship, a split between rival factions, a public shaming, a run-in with the legal system. The choice is rarely brought on by empathy for people they have been conditioned to despise. “We call it ‘defaulting back to the mean,’” Simi said. This is when people exit violent extremist groups, only to rejoin the “polite racists

This is why former white supremacists like Brown often struggle with persistent racist feelings, even after they’ve cut ties with their pasts. Counseling former extremists about their childhood, as a treatment method on its own, will not work. Simply exposing them to diverse people won’t do the job either. Any solution will be more complex, because hate is more complex. It’s a socially, historically, and institutionally bred behavior that embeds in the psyche. Solving the problem is not a matter of just getting someone to leave a hate group. Hate and racism become part of their core identity, Simi said, and for many who leave hate behind socially, abandoning it psychologically is a much harder process. Simi calls this the “hangover effect.” Hatred has an insidious way of hanging on, never quite disappearing, even for the ones who want to wish it away the most.

Despite the research, historical notions of racism as a “disorder” that can be measured and treated continue to imbue modern race science. The widely used Implicit Association Test, for example, which measures how mental associations can influence behavior—how our minds link concepts, assessments, and stereotypes about other people—characterizes implicit bias as an infection we are exposed to throughout our lives. Psychiatrists Carl Bell and Edward Dunbar describe racism in the 2012 Oxford Handbook of Personality Disorders as a kind of “public health pathogen.”

Such thinking about racism as a disease that can be treated has led some scientists to forge ahead in search of a neurological or pharmaceutical cure. The idea that, one day, people might be able to treat racism as easily as they alleviate heartburn is certainly tantalizing. Indeed, in 2008, a philosopher proposed the idea of a “pill for prejudice,” to reduce the influence of bias on judicial decisions, after the drug propranolol—a beta-blocker that relieves hypertension and reduces anxiety by interrupting stress hormones and is used to treat post-traumatic stress disorder—was found to also reduce implicit bias in a sample of white people for a short period of time.

Other experiments have shown that it is possible to counteract racist thoughts at least temporarily. In six studies involving nearly 23,000 people, Calvin Lai found that playing up vivid counter-stereotypes was very effective at reducing biases within individuals. In one experiment, researchers asked subjects to imagine “being kidnapped by an evil middle-aged white man, only to be saved by a dashing young black hero.” Within minutes, the subjects had decreased the intensity of their biases and the speed at which they made prejudiced associations by 50 percent. There’s a catch, however: “After just a day or a couple of days,” Lai said, “these effects fade away.

The idea of “implicit bias” began to take off in American workplaces and society a decade ago, as corporations looked for alternatives to “diversity training,” an $8 billion effort that has been largely unsuccessful. Studies have found that, rather than encouraging participants to embrace people of all colors and creeds, forced classes on diversity often backfire, making people more defensive and divided. Implicit bias, by contrast, is rooted in the idea that we all possess inherent prejudices. Instead of mandating employee training on racial sensitivity, diversity awareness, compliance with antidiscrimination laws, and lessons on how to better integrate the workplace, companies in recent years have spent millions of dollars on new programs that train employees to recognize their biases—the idea being that if we can simply acknowledge our prejudices and blind spots, we can overcome them. Implicit bias trainings often involve videos, slideshows, or personal anecdotes that reveal how a person’s individual biases may influence a particular situation. Approaches include talking through experiences, writing privately about racist feelings, watching videos of racist incidents, role-playing, listening to personal stories of discrimination, and learning lessons about history and policy.

Yet laboratory studies have shown that, like the diversity trainings, anti-bias initiatives may also be ineffective at combating racism. Some of the exercises probably do have an effect, Jeni Kubota said. The problem is “they only work for a little bit”—the same way the subjects in Calvin Lai’s experiment were only able to dampen their biases temporarily. “Then you go back out in the real world, you get reinfected with these associations, and any cognitive intervention that you did diminishes over time,” Kubota said.

The problem with viewing racism in medical terms is that it confines racism to a disease in the body or mind, something biological that may be treated—even cured—without the need for larger societal changes. “It assumes we can just fix it with a pill or download screensavers of Denzel Washington and Lupita Nyong’o and all of a sudden you will stop being racist—a pain-free, recreational fix for what is hundreds of years of historically fraught problems,” said Jonathan Kahn, a professor at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and the author of Race on the Brain: What Implicit Bias Gets Wrong About the Struggle for Racial Justice.

This is the frustrating reality of racism that science has illuminated. Much as we’d like to believe that white supremacists exist on the radical fringe, and that what it will take to cure them is to reintegrate them into mainstream society, the truth is not so simple. Racism courses through mainstream society, too, lurking in the brains of people like Shannon Brown and her family. Similarly, corporate anti-bias trainings suggest a straightforward set of steps for alleviating prejudice. But the idea that bias is somehow “inherent” in all of us—a fact of life, something normal and natural, which simply must be recognized and accepted—is deeply unsatisfying. Why should we settle for a society in which racism is allowed to persist?

Neuroscience has exposed the shortcomings of the current approaches to combating racism. But it has also revealed that curing hate is theoretically possible—under the right circumstances, and with enough mental effort. And one day, science may figure out a simple “cure.” To that end, researchers have started to study the members of hate groups more closely, to try to understand whether extreme racism operates in the brain the same way bias in the general public does. Simi, one of the leading experts in this field, has spent the last 20 years studying neo-Nazis in order to understand their motivations and behavior.

In a pilot study this year, Simi and researchers at the brain development lab at the University of Nebraska used fMRI scans to compare five former white supremacists with nonextremists. The subjects viewed racially charged images, such as swastikas, Confederate flags, or images of people in interracial relationships. The brain scans revealed significant differences in neurological activity between the former white supremacists and the control group. “So it’s not just a difference by random chance,” Simi said. “Most of the heightened activation was occurring in one part of the prefrontal cortex in particular,” the region associated with regulating moral behavior.

The pilot study is too small to draw conclusions, and Simi is working to expand the research to include a larger pool of former white supremacists, current white power group members, and nonextremists. But Simi believes he is on the path to identifying exactly how extreme racism operates in the brain. It is slow, expensive, difficult work, but the impetus for it, Simi said, came from his interviews with former white supremacists, who would tell him, “I try and try, and I just can’t stop hating people.”

For any authoritarian government, defining reality is crucial to exercising power. History becomes a series of myths that justify and animate the regime’s actions; truth becomes a weapon to be wielded against enemies; lies become a shield for supporters and sympathizers to escape scrutiny. Trump has adopted one authoritarian trick after another to his playbook over the years. But obscuring truth with theater will always be his signature act.

On Sunday, after a peaceful march protesting U.S. immigration policies on Sunday, some members of a Central American migrant caravan tried to cross the border at the closed San Ysidro port of entry. Border Patrol agents responded by firing tear gas at the crowd to drive them away. Among those caught up in the incident were young children traveling with their parents.

Liberals were shocked. But conservative media outlets eagerly devoured the imagery. Fox News Channel aired wall-to-wall coverage of the saga over the past 48 hours, casting asylum-seekers as an invading force and justifying extraordinary measures to stop them. Rob Colburn, the president of the Border Patrol Foundation, told Fox & Friends that pepper spray wasn’t harmful because “you could actually put it on your nachos and eat it.” Other commentators responded with unnerving enthusiasm. “Watching the USA FINALLY defend our borders was the HIGHLIGHT of my Thanksgiving weekend,” right-wing pundit Tomi Lahren wrote on Twitter.

Cruelty, I noted in May, is both a means and an end for the Trump administration, which aims to curtail legal and undocumented immigration to whatever extent Congress and the courts will allow. And on Sunday, the sensationalism through which the administration carries out that cruelty was on full display. The White House, over the past two years, has taken every opportunity it could to exacerbate the tensions that ultimately led to this moment: threatening to close the border if migrants in the caravan tried to lawfully seek asylum, shutting down the channels by which they could obtain it, deploying thousands of soldiers to the border in a campaign stunt, signing an executive order to ban some asylum claims, and more. It’s hard to see what more they could have done to manufacture the conditions—desperate migrants denied internationally recognized legal processes for entry—under which Sunday’s clash unfolded.

It’s hard to see what more they could have done to manufacture the conditions under which Sunday’s clash unfolded.Favoring chaotic, freewheeling press scrums instead of reading policy memos, Trump prefers to govern by spectacle over substance. Immigration is one of the few policy spheres where he can do both. Whether consciously hewing to a premade plan or not, the White House’s sequence of policy decisions effectively engineered a border crisis with clear political benefits. With Democrats now set to retake the House in January, this penchant for governing through public surreality will only get more aggressive as his opposition gathers strength.

Part of the problem for Trump and his allies is that, in absolute terms, there isn’t really an “immigration crisis” in the way they conceptualize it. Measuring undocumented immigration can be tricky, but most indicators suggest it has been declining over the past ten years. Apprehensions for illegal border crossings have dropped sharply from their heights under the George W. Bush administration, for example, even as the amount of money spent on border control has more than doubled. Fewer children are born in the U.S. to undocumented parents each year. Almost one million fewer undocumented immigrants are believed to live in the U.S. now than before the Great Recession, when many of these trends began to change.

The Trump administration already imposes labyrinthine barriers to people seeking asylum in the United States. The key threshold is whether an applicant faces a credible fear of persecution if they are returned to their home country. Many applicants fail to cross this hurdle: Immigration officials only granted 20 percent of the asylum requests made during the 2017 fiscal year, the last period for which full Justice Department statistics are available. Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who oversaw the nation’s immigration courts, issued multiple rulings that raised the threshold for asylum claims even higher over the past year.

Trump, like many authoritarian figures, understands the value of spectacle. In some ways, this is the defining trait of the president’s life. Trump captured the presidency by casting himself as a successful businessman whose vast personal fortune would insulate him from Washington’s corruption. His career, however, displays no extraordinary business acumen or particular skill at dealmaking. An exhaustive New York Times investigation earlier this year found that Fred Trump, the president’s father, used his own wealth to keep his son afloat as Donald bounced from one failed venture to the next throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

What the president truly excels at is marketing himself. Even as his father kept open a spigot of cash to prop up his son’s enterprises, Donald Trump cultivated a public image of wealth, extravagance, and success. In recent years, his image became an asset of sorts that he burnished with a reality-TV show and leased to hotel properties owned by savvier entrepreneurs around the world. Trump University, his defunct business seminar program, was the ultimate expression of this strategy. While it promised to reveal Trump’s unique insights into real estate investing, the program often amounted to a predatory scheme to extract tens of thousands of dollars from financially troubled “students.” In a way, they learned the secrets to his success better than most.

The president brings the same carnival-barker mien to governing a superpower. He showed little interest in the legislative details of the GOP’s effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act last year, though he was ardent in demanding that it happen in some fashion. Trump took a similarly hands-off approach during the successful push to overhaul the nation’s tax code a few months later. Trump’s priority was securing a victory, regardless of what form it took. Presidents don’t always delve into the minutiae of the legislative process, but rarely are they so uninterested in it.

This approach has occasionally backfired when it comes to administrative rule-making. Former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt’s high-profile and ham-fisted efforts to roll back environmental regulations have fared poorly under judicial scrutiny, for example. (Andrew Wheeler, his more low-key replacement, has had better luck.) Perhaps the best example is Trump’s Muslim ban, which initially began as a slapdash executive order that sparked chaos at U.S. airports and a swift rebuke from multiple federal courts. The Supreme Court ultimately upheld the third iteration in a deeply divided 5-4 ruling that Justice Sonia Sotomayor compared to Korematsu v. United States, the infamous 1944 ruling that allowed Japanese internment camps, in dissent.

Whenever the courts rule against Trump on border-related matters, he responds by challenging the judiciary’s legitimacy. After a federal judge in California ruled against his asylum ban earlier this month, Trump denounced him last week as an “Obama judge” and threatened to take action against the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, where he’s been handed multiple legal defeats. That prompted an extraordinary rebuke from Chief Justice John Roberts. “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges,” he told the Associated Press in a statement. “What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them.”

Trump responded to the chief justice in his usual fashion. “We need protection and security—these rulings are making our country unsafe!” he wrote on Twitter. “Very dangerous and unwise!” This is his strategy in a nutshell: to eliminate nuance, to flatten discourse, to polarize public opinion, and to delegitimize any obstacles in his way. George W. Bush and Barack Obama both sought grand bargains in Congress to change the nation’s immigration system. Trump, by comparison, is amplifying the nation’s divisions, aided by a feedback loop in the conservative media ecosystem and the executive branch’s broad latitude in immigration matters.

The benefits for the latest spectacle—purchased at the price of human suffering—are many. It helps shift the narrative away from the president’s shellacking in the November midterms, where Americans roundly decided to elect a Democratic House of Representatives to keep him in check. Stoking fear along the border distracts the growing economic damage wrought by his trade war, from his dwindling and dispirited White House staff, and from the ever-looming shadow of special counsel Robert Mueller. Telling the American people that he’s saving them from hordes of criminal migrants and throngs of undocumented immigrants sounds better than admitting he’s trying to leave office with a whiter America than when he was sworn in.

The impact is most tangibly felt at the U.S. border, where hundreds of migrants find themselves in a bureaucratic purgatory of sorts while they wait for a chance to apply for asylum. Americans, too, could soon feel the brute force of Trump’s approach to governance, however. With Democrats set to take over the House of Representatives in January, the president will have a new adversary to wrestle with. The looming threat of multiple Democratic inquiries into his administration, his businesses, and his campaign could prompt Trump to try similar hard-edged tactics to change the narrative. The spectacle, along with the all-too-real pain with which it is carried out, and from which it is intended to distract, is just beginning.

No comments :

Post a Comment