The Donald J. Trump Foundation was an audacious grift, even by the standards of its namesake. Charitable foundations are supposed to operate under a simple premise: They receive certain tax exemptions when it comes to receiving and disbursing their funds, and in turn, those funds will be funneled into good works for society’s benefit. For Trump’s charity, however, those good works largely amounted to crass self-enrichment—a guiding principle throughout the president’s life and political career.

The Washington Post’s David Fahrenthold reported two years ago that the Trump Foundation’s most generous expenditure, totaling $264,361, went to renovations for a fountain outside the Trump-owned Plaza Hotel in New York City. Its smallest contribution—just $7—appears to have been used to pay for Donald Trump Jr.’s registration fee for the Boy Scouts of America. In one instance, Trump auctioned off a six-foot-tall painting of himself to charity, then spent $20,000 from the foundation’s funds to purchase it.

New York thinks it can find a better use for the money. Barbara Underwood, the state’s attorney general, announced on Tuesday that the president agreed to shut down the foundation and let state officials disperse its remaining funds to genuine charitable organizations. “This is an important victory for the rule of law, making clear that there is one set of rules for everyone,” Underwood said in a statement announcing the agreement. Her office is still pursuing more than $2 million in restitution from Trump and restrictions on his family’s involvement in non-profit organizations in the state.

An investigation by Underwood’s office uncovered a clear pattern of instances where the Trump family misused charity funds. The foundation cut checks for well-publicized donations during Trump’s presidential campaign, transmogrifying charitable funds into politically beneficial expenditures. It shelled out hundreds of thousands of dollars to settle legal disputes involving Trump himself or his companies. Normal safeguards like an active board of directors, standard accounting practices, and grant-making policies did not exist. The charity itself, investigators said, “is little more than an empty shell.”

“In sum, the Investigation revealed that the Foundation was little more than a checkbook for payments to not-for-profits from Mr. Trump or the Trump Organization,” the attorney general’s office said in a lawsuit this summer. “This resulted in multiple violations of state and federal law because payments were made using Foundation money regardless of the purpose of the payment. Mr. Trump used charitable assets to pay off the legal obligations of entities he controlled, to promote Trump hotels, to purchase personal items, and to support his presidential election campaign.”

Though the Trump Foundation was an impressively brazen scheme, it’s far from the only one bearing the president’s name. Trump agreed to pay $25 million to settle a multi-state class-action lawsuit against Trump University, his now-defunct real-estate seminar program. Court filings showed how the seminars preyed on customers’ financial anxieties so they would fork over thousands of dollars for mundane lessons about buying and selling property. This undercut Trump University’s main selling point: that “students” would be able to draw upon its eponymous founder’s reputation for savvy real-estate deals.

Even this reputation isn’t grounded in anything, though. The underlying basis of Trump’s political career is his public image as a self-made real-estate magnate. Careful scrutiny by journalists and investigators, however, has shown this to be largely mythical. It wasn’t business acumen that helped Trump establish a foothold in New York real estate in the 1980s and 1990s, but a steady infusion of at least $413 million from his father through dubious tax practices. Trump’s inflated reputation is a source of income in and of itself. Many of the overseas hotels bearing his name don’t even belong to him: He simply licenses his image to real-estate developers overseas, giving a branding edge to them and a reliable stream of profit to him.

You’d be hard-pressed to find an aspect of the president’s life that isn’t marked by grifting. The Trump campaign and its allies heard multiple offers of assistance from Kremlin-linked figures while Trump’s personal lawyer tried to secure a hotel deal in Moscow. His inaugural committee later raked in more than $100 million—more than twice the sum of his predecessors—from wealthy donors that largely went unaccounted for. A ProPublica investigation found that the Trump Organization may have overcharged the committee for use of Trump’s Washington hotel, raising questions about whether any illegal self-enrichment took place. (Federal prosecutors are reportedly investigating the matter.) Foreign governments have also poured money into the Trump Organization’s properties, which may violate a constitutional ban on federal officials receiving foreign profits.

Ironically, some of these schemes likely would have gone unnoticed if Trump had never run for president. Fahrenthold, of the Post, began his Pulitzer Prize–winning investigation into Trump’s charitable donations after then-candidate Trump handed out oversized checks to veterans’ groups in campaign stunts. And the illegal hush-money payments that eventually led former Trump attorney Michael Cohen to start cooperating with the federal prosecutors likely wouldn’t have been made if Trump wasn’t trying to win the presidency. Becoming president has subjected Trump’s hollow empire to a level of scrutiny that he never imagined. The question is whether any of it will remain by the time he leaves, or is forced from, the White House.

Let’s say Washington is a swamp, as Trump calls it. Then lobbyists are the gators, and strong ethics rules are the fence that keeps Americans from getting bit. In President Donald Trump’s swamp, the gators keep getting bigger and the fence is in tatters.

On Saturday, Ryan Zinke submitted his resignation as secretary of the Interior Department, the seventh-largest agency responsible for most of the nation’s natural resources and public lands. Zinke will be replaced—at least temporarily—by David Bernhardt, a former high-profile lobbyist for the fossil fuel industry and the Interior’s current second-in-command. As a lobbyist, Bernhardt worked on behalf of several oil companies that he’ll soon be in charge of regulating. He’s been called “a walking conflict of interest” by his critics.

Bernhardt’s ascent follows Trump’s announcement last month that a former lobbyist for the coal industry would soon be nominated to lead the Environmental Protection Agency. Andrew Wheeler has been serving as acting administrator since July, after former EPA chief Scott Pruitt resigned amid numerous ethical scandals. As a lobbyist, Wheeler represented Murray Energy—a coal company whose CEO literally sent Trump a wish list of all the environmental regulations he wanted dismantled. Trump’s EPA, now led by Wheeler, is on track toward fulfilling almost all those requests.

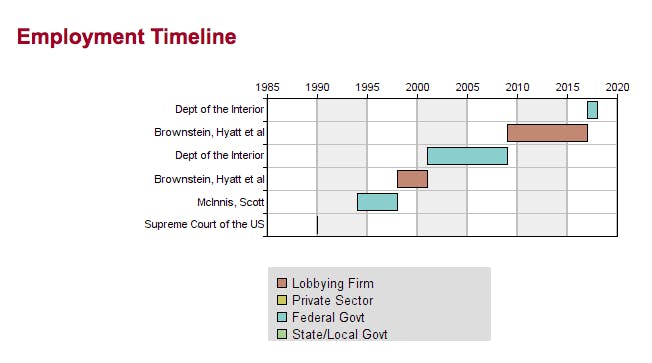

David Bernhardt, the Interior Department’s new acting chief, has been switching between lobbying jobs and government jobs since the early 1990s.Center for Responsive Politics

David Bernhardt, the Interior Department’s new acting chief, has been switching between lobbying jobs and government jobs since the early 1990s.Center for Responsive PoliticsIt’s alarming to know that two men who became rich by helping polluters dismantle environmental protections are about to lead the two most important federal agencies protecting public lands, wildlife, and human health. Many environmentalists believe that fossil fuel lobbying should disqualify Wheeler and Bernhardt from these positions.

But the mere presence of lobbyists in Trump’s cabinet doesn’t raise the alarm of government ethics experts. “The revolving door is a basic part of the Washington Establishment,” said Laura Peterson, an investigator at the Project on Government Oversight. “People go back and forth between the public and private sectors all the time.” It makes sense why they would; government agencies regularly deal with lobbyists when they’re crafting regulations, so they hire people who are familiar with the process.

The Trump administration does, however, seem “particularly comfortable stacking high-level posts with former lobbyists whose policy proposals are like a corporate Christmas list,” said Peterson. As ProPublica revealed in March, “At least 187 Trump political appointees have been federal lobbyists, and despite President Trump’s campaign pledge to ‘drain the swamp,’ many are now overseeing the industries they once lobbied on behalf of.”

These former lobbyists are not only flooding the government. They’re entering “a wild west environment where anything goes,” said Walter Shaub, the former head of the U.S. Office of Government Ethics from 2013 to 2017, when he resigned out of “disappointment” with Trump.

Shaub emphasized that previous administrations had “a lot” of industry members. “But past Republican presidents were similar to Democratic presidents in at least supporting the government ethics programs,” he said. President Barack Obama, for example, signed an executive order in 2009 prohibiting the government from hiring people who had been a lobbyist in the previous year. Special waivers could be granted, but had to be made public. A hired former lobbyist would also be prohibited from working on any issue on which they had previously lobbied.

Trump repealed Obama’s policy when he took office, replacing it with an executive order that he claimed would more effectively “drain the swamp.” But the ethics order has proven much weaker than Obama’s in practice, Shaub said. Now, lobbyists can be hired for any government position. Lobbyists can also work on issues where they have a direct conflict of interest, provided they get a waiver. And Trump has been giving these waivers out like candy to the most powerful people in his administration—at least 37 “to key administration officials at the White House and executive branch agencies,” according to a March report from the Associated Press.

But the total number of government officials with conflict-of-interest waivers is likely much more than 37, for two reasons: Trump’s ethics policy, unlike Obama’s, does not require waivers to be made public. His waivers are also often extremely vague, said Shaub, who now works for the nonprofit Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. “It’s impossible to count the number of people listed on a waiver, because they describe the type of person they’re waiving rather than directly naming them,” he said. The waivers granted to ex-lobbyists also “don’t offer any explanation” for why they’re needed.

This secrecy is perhaps the most troubling part of Trump’s lobbying policy. Of course, we want nothing more than to assume that government officials will act in good faith. But American history is littered with examples of those who were able to abuse their power thanks to a lack of transparency and oversight. The current administration is contributing more than its fair share to that ignominious list. Though he ran on a promise to “drain the swamp,” Trump is feeding with gators and letting them roam free—then asking us to trust him that the gators won’t bite.

The #MeToo movement has toppled dozens of prominent men in American society over the past 18 months. Some other English-speaking countries, however, have only seen modest or muted reckonings. As Australia’s ABC News put it in May, “There’s been a steady stream of #MeToo headlines out of the US, but it’s more of a trickle in Australia.”

What explains this disparity? Are Australian men simply more virtuous than their American counterparts?

It’s doubtful. The likelier answer is that their misdeeds are better shielded from public scrutiny by their respective countries’ libel laws. The American legal system gives journalists and publications extraordinarily broad leeway when publishing allegations that may be considered defamatory by the subject. Other English-speaking countries, especially those that inherited the British legal system, offer only a lesser degree of protection to reporters from litigation.

Those laws have consequences not only for those with stories to tell, but for democratic society as a whole. Lower libel standards all too often allow wealthy and powerful individuals to use their resources to bully those whom they’ve wronged—and the news organizations that learn about it—into silence. It’s no surprise that people like President Donald Trump are so hostile to press-freedom laws as they currently stand. It’s also why efforts to undermine them should be vigorously opposed.

In Australia right now, Geoffrey Rush, a star in the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise and one of his country’s most famous actors, is locked in a legal battle with The Daily Telegraph. The Australian newspaper published vague allegations that in the fall of 2017, Rush behaved inappropriately with an unnamed fellow cast member during a theater performance in Sydney. Rush denied the allegations and sued the Telegraph last December in federal court.

During the trial this fall, actress Eryn Jean Norvill testified that she was the cast member mentioned in the Telegraph story, though she said she had only made a confidential complaint to the theater company and hadn’t contacted the newspaper. She described a persistent pattern of unwanted contact and gestures by Rush during rehearsals, saying they made her feel “trapped” and “frightened.” A verdict is expected in early 2019, though it’s unclear whether her account persuaded the judge. “It is so vague he may not know what he has allegedly done,” he remarked in court during the trial.

Defamation trials are a familiar sight in Australia and other countries that inherited the British legal system. That Rush’s case even went to trial shows how different the country’s legal standards are from America’s, where the lawsuit likely would have been quashed at an earlier stage in the proceedings. “Geoffrey Rush would have zero chance of securing a successful libel verdict if he sued in the United States over the ‘inappropriate behaviour’ story,” Australian legal journalist Richard Ackland wrote last month.

Under American law, whoever sues a journalist or publication for libel must prove that the defamatory material was false. If they’re a public figure—someone with power and influence—they must also show that the material was published with “actual malice” and a “reckless disregard” for the truth. The Supreme Court first established this high threshold in the landmark 1964 case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. Justice William Brennan, writing for the majority, cited the “profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.”

Australia does not have an equivalent to the First Amendment or even a Bill of Rights. The country’s laws instead place the burden on the journalist or publication to prove in court that what they wrote is true. This makes it more legally perilous to publish allegations about events that took place years or decades earlier, or to rely upon personal accounts and experiences alone. In cases involving sexual misconduct that span an entire person’s career, it’s a formidable threshold to overcome. Litigation is expensive, and many news outlets—not to mention most individual journalists—can’t afford an extended, costly legal battle.

Australia’s woeful defamation laws have even allowed Sydney to seize, from London, the title of “libel capital of the world.” Britain was notorious for its weak libel protections before Parliament heightened its standards in 2013. The Sydney Morning Herald reported last year that the Australian province of New South Wales, which includes Sydney, sees as many defamation lawsuits as England and Wales, which has eight times the population. Yael Stone, an actress who came forward this month with similar allegations against Rush, recently told the Times’ Bari Weiss that she feared going public because of the potential legal hazards.

Australia’s aversion to press freedom extends beyond libel laws. Earlier this month, a local court convicted Cardinal George Pell on five counts related to sexual-abuse charges that span decades. Pell, one of the most senior Catholic clergy ever accused of sexual abuse, was a prominent Vatican figure and a close adviser of Pope Francis until the allegations became public. His conviction was, by any definition, a major news story.

But Australian media outlets were barred by a judicial order from publishing any details about Pell’s conviction. The result was surreal: Australian media outlets either obliquely referred to the conviction of an unnamed person, or simply chose not to report the news at all. The Daily Telegraph responded by publishing a front page that read “IT’S THE NATION’S BIGGEST STORY” with no other description of what happened and an editorial denouncing the state of affairs. Thanks to social media, many Australians were able to learn what happened, rendering the entire state of affairs even more absurd.

Even foreign news outlets with reporters in Australia are affected. The New York Times published an unusual article on the quandary and its implications last week, all without mentioning any names. “The Times is not publishing the latest news of the case online, and it blocked delivery of the Friday print edition to Australia, to comply with the judge’s order,” reporter Damien Cave wrote. “The Times’s lawyers in Australia have advised the organization that it is subject to local law because it maintains a bureau in the country.” (The New Republic does not have an Australian bureau.)

Cave noted that Australian officials defend orders like these on the idea that suppressing media coverage is necessary to insulate potential jurors from bias. Pell, for instance, is expected to face more criminal trials in Australia related to the allegations against him. The American judicial system has much greater faith than its Australian counterpart in the average person’s ability to render a verdict based on the evidence presented to them in open court. In extraordinary circumstances, a U.S. judge could simply order the jury to be sequestered for the duration of the trial. Depriving a handful of jurors of the free press is far preferable to depriving a nation of it.

Press-freedom cases and legal thresholds for libel lawsuits aren’t the sexiest topics in the world, but they play a profound and often invisible impact on a democratic society. They afford the less powerful members of society a measure of protection from the litigious whims of the wealthy and the well-connected. They help make possible a public discourse in which allegations of wrongdoing can be made without fear of reprisal and bankruptcy. And they tilt the playing field away from those who are most likely to abuse it.

It’s no surprise, then, that Trump is the foremost opponent of America’s libel laws. His public and private life are defined by unsavory behaviors: allegations of tax evasion and consumer fraud, accounts of sexual misconduct by at least nineteen women, hush-money payments for two alleged extramarital affairs, and more. Trump has a lot to hide, and he’s lamented his inability to hide it. But because the nation’s libel laws are written at the state level and shaped by Supreme Court precedents, the president has virtually no power to change them.

That hasn’t dissuaded him from threatening to do so. “We’re going to open up those libel laws,” he told supporters on the campaign trail. “So when The New York Times writes a hit piece which is a total disgrace or when The Washington Post, which is there for other reasons, writes a hit piece, we can sue them and win money instead of having no chance of winning because they’re totally protected.” His frustration is a high compliment for the American approach to libel and press freedom, and a good example of why Australians should rethink theirs.

Joe Biden is feeling so good about his 2020 chances, he’s already thinking about a running mate. Last week, the Associated Press reported that Biden’s advisers have discussed the possibility of teaming with a younger candidate—Beto O’Rourke’s name has come up—to fend off concerns about the 76-year-old’s age. With the 2020 Democratic National Convention more than 18 months away, such talk may seem premature. But the early months of 2019 likely will see a glut of Democrats declaring their candidacy, and Biden is poised to begin the race in pole position. He has posted sizable leads in national polling and, over the weekend, led the first poll of likely Iowa caucus-goers by a large margin.

Biden is the early frontrunner for obvious reasons. He served for eight years as the vice president of Barack Obama, the most popular figure in Democratic politics, and did so with an avuncular charm that was once seen as a political liability, but has aged well under a crass president. He is also aided by the sheer size (likely several dozen candidates) and opacity (no major figures have announced their candidacy yet) of the field. He also may be benefitting from not having had any direct involvement in politics since leaving office two years ago; unlike elected Democrats, he hasn’t had to make any difficult decisions or defend his response to the Trump administration. He is, in short, an elder statesman of the party, and is being treated as such.

But these benefits have significant drawbacks, all of which will begin to appear once Biden actually starts running for president, which he is expected to do. Hillary Clinton, after all, was in a very similar position in advance of the 2016 contest, having enjoyed a surge in popularity from her successful stint as President Obama’s secretary of state through her retirement from public office. In 2013, polling suggested she was the most popular politician in America. But reentering politics swiftly changed that: Her favorability plummeted after she announced her race for president in 2015. This is not a perfect comparison, for reasons I’ll explain, but to some degree this happens to all former politicians who rejoin the fray.

We may already have hit peak Biden, and it’s all downhill from here.

Biden’s public image has been bolstered by his distance from public life. Even as vice president, he largely kept his hands clean of everyday politics in Washington. If Obama was seen as the brain of the administration, Biden was its heart and soul: an emotional man of the people, simultaneously macho and unafraid to cry in public, who famously pressured Obama (albeit accidentally) into supporting gay marriage. That perception has only grown in his retirement, as Trump’s rise has fueled a nostalgia for more decent times in American politics.

But if Biden runs, his past will be raked over—and his political record looks increasingly checkered in today’s light.

Biden shamefully failed to protect Anita Hill after she accused Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment in 1991. He refused to call corroborating witnesses and did nothing to block disgusting personal attacks from Republicans. This was already seen as a weakness in the #MeToo era, but has become even more damaging after Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings. (Biden has made things worse by failing to apologize to Hill.) Republicans, particularly Trump, will make much of Biden’s handsiness, but his treatment of Hill is by far his biggest liability.

Biden’s legislative record also contains a series of blights. As a representative of Delaware, one of America’s most corrupt states, Biden is notoriously cosy with financial interests. He spent years advocating for a law that made it significantly more difficult for consumers to declare bankruptcy, before it finally passed in 2005. Elizabeth Warren called it an “awful bill” and support for it likely hurt Hillary Clinton when she ran for president in 2016. Like Clinton, Biden supported the Iraq War and the 1994 crime bill, which made mass incarceration significantly worse. Unlike Clinton, Biden still defends the crime bill, which he praised in his 2017 memoir, Promise Me, Dad. If critics were to dig even further into Biden’s past, they would find that he went to great efforts to suppress busing and other school integration efforts and was against reproductive rights before he was in favor of them.

Biden, if he runs, undoubtedly will argue that he is the only Democrat who can truly connect with the white, blue-collar voters who have fled the party in recent years. He has always reveled in the perception that he’s an authentic politician who understands the so-called common man in ways that his colleagues do not. Even one of his greatest political weaknesses—his penchant for gaffes—can be favorably spun: He’s a guy who says what he thinks, and that worked out pretty well for Trump, didn’t it?

In Promise Me, Dad, Biden shows that he’s not inflexible, making the case that, had he run for president in 2016, he would have ended tax breaks for the wealthy and advocated for a $15 minimum wage. His laudable decision to turn down a $38 million speaking deal also suggests that he can read the political winds. But in a primary that may revolve around Medicare for All and a Green New Deal, Biden’s obvious centrism and voting record will be liabilities that his off-the-cuff style may make worse—it’s easy to imagine the punchy, impulsive Biden doubling down when he should be recanting. At the same time, reminders of Biden’s past stances and behavior will damage the kindly Uncle Joe image he’s cultivated over the past decade.

A Biden candidacy, like Clinton’s, would serve as a reminder of the many flaws of a party establishment that an increasing number of Democrats would like to overthrow (or at least overhaul). But there are some important differences between Biden’s situation, if he runs, and Clinton’s. Biden doesn’t have the same exaggerated scandals in his closet that Clinton did. He also won’t face a sexist backlash. And perhaps most important, Biden would enter the race as the frontrunner, but not the presumptive nominee. Clinton really only had to fend off a single challenger, a septuagenarian democratic-socialist who rarely even identifies as a Democrat. Biden will have to beat out as many as 34 candidates for the nomination. The odds are simply much worse.

Beto O’Rourke is running, or so it increasingly seems. After coming closer to winning statewide office than any Texas Democrat in decades, the three-term congressman from El Paso acknowledged that he was considering a White House bid and met quietly with Barack Obama. Louis Susman, a major Democratic fundraiser who backed the former president’s nascent 2008 campaign, has said he would support O’Rourke. Even some of his rivals think he should run. The chief strategist for Ted Cruz, the senator whom O’Rourke nearly unseated, said the congressman has a “hot hand.” “If you have a hot hand, take it,” Jeff Roe told the House Chronicle. “He would win Iowa.”

Would a politician who did little to distinguish himself in Congress, and whose most recent campaign ended in defeat, really stand a chance of winning the Democratic nomination? As The New York Times noted recently, the Democratic primary is “expected to be the party’s most wide open in decades,” and O’Rourke “has emerged as the wild card of the presidential campaign-in-waiting for a Democratic Party that lacks a clear 2020 front-runner.” O’Rourke’s campaign for Senate broke fundraising records, largely on his strength with small donors. In a straw poll released last Tuesday by the progressive group MoveOn, O’Rourke came in first, edging out Joe Biden. In two polls since then, one national and one in Iowa, he trailed only Biden and Bernie Sanders

If O’Rourke does decide to run, though, he’ll be competing not only against a multitude of Democratic hopefuls, but against history. Since America’s founding, congressmen have fared poorly in presidential elections, due to a number of systemic hurdles. The question is whether O’Rourke is exceptional enough to overcome them.

There have been as many reality stars directly elected to the presidency as members of the U.S. House of Representatives: James Garfield is the only sitting congressman to win the White House, a feat he accomplished in 1880.

O’Rourke gave up his seat to challenge Cruz, so he could not join Garfield in that honor, but it would be extremely rare nonetheless for a politician who most recently was a congressman to win the presidency. Only one other person, Abraham Lincoln, whose prior elected office was in the House has gone on to be president. Eighteen congressmen have ever gone on to be elected president, though the majority were governors, senators, or cabinet officials in the interim. (John Quincy Adams also served in the House, but not until after his presidency.)

History is somewhat more favorable for presidential aspirants in the other chamber of Congress. While only three sitting senators—Warren Harding, John F. Kennedy, and Barack Obama—have gone directly to the Oval Office, they appear much more frequently on presidential tickets, both as candidates and running mates. Aside from 2012, in which former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney and Wisconsin Representative Paul Ryan challenged Obama and Biden, every election going back to 1992 featured a sitting senator somewhere on the ticket. In the last hundred years, eight elections have featured sitting senators on major tickets; one, in 2008, featured sitting senators atop both major tickets (Obama and John McCain). In that same span, there have only been six elections in which a sitting senator did not appear somewhere on a major party ticket.

By contrast, no sitting congressman has even led a major party ticket since Garfield, and not since William Jennings Bryan in 1908 has someone led a major party ticket after most recently serving as a congressman. (Bryan lost to William Howard Taft by 30 points.) Until Ryan ran with Romney, no sitting member of Congress had even appeared on a major party ticket since 1984, when Michael Dukakis tapped Representative Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate—only to lose to Vice President George H.W. Bush and Indiana Senator Dan Quayle. In fact, just three sitting representatives have gone directly to the vice presidency, the most recent being John Nance Garner, who was elected with Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932.

Why are representatives so poorly represented in presidential politics? It’s a combination of several factors: U.S. representatives usually lack the visibility, resources, and sometimes the experience of politicians who hold statewide office.

“I think that anyone who’s been a governor or a senator for five minutes gets treated as a more serious candidate,” David Karol, an associate professor of government and politics at University of Maryland, told me. “And that’s typically less true of members of the House, unless they’ve been in a leadership role.”

The structure of the House itself works against presidential hopefuls. Being one of 435 House members, versus one of 100 senators, makes it more challenging to get national attention. Unlike senators, who serve six-year terms, representatives face reelection every two years and thus are particularly accountable to their districts; there is simply less time to mount a nationwide campaign. Congressmen also represent far smaller districts and may have less experience with broader constituencies.

“They may have high approval ratings from one small subset of people,” said Lara Brown, director of the Graduate Program in Political Management at George Washington University and author of Jockeying for the Presidency: The Political Opportunism of Aspirants. “But often times, their constituency is not representative of their state and certainly not of the United States as a whole.”

All that can put them at a significant disadvantage in access to the daunting funds and resources needed to compete for president. “A typical congressional race is essentially a glorified city council race,” said Republican strategist Ken Spain. “Running for higher office requires a donor network, a sophisticated campaign team that can operate across multiple cities in multiple states, and experienced hands when it comes to strategy and execution. Sure, you can be a one-man-band candidate. But those kinds of candidates come in flashes and fade quickly.”

O’Rourke isn’t the only congressman reportedly considering a White House bid. California’s Eric Swalwell, Hawaii’s Tulsi Gabbard, and Ohio’s Tim Ryan are all rumored candidates, too. And one has already declared his candidacy: Maryland’s John Delaney entered the 2020 race way back in July 2017.

A wealthy businessman, Delaney has so far been able to largely fund his own campaign, allowing him—at least in theory—to rely less on donors. He’ll also have time; the three-term representative is retiring from Congress so that he can campaign full time. While he remains a mostly unrecognizable figure on the national stage, he’s spent months working to build up a profile in Iowa and New Hampshire, and is banking on strong performances in the important early primary states to catapult him to nationwide recognition.

“When I win the Iowa caucus,” Delaney told me, “everyone who’s focused on the presidential election in this country is going to know who I am.”

Delaney seems to have built some name recognition in the states, but will that be sufficient if and when more prominent figures—Biden, Sanders, Elizabeth Warren—officially enter the race? “Delaney is a very long shot,” Karol said, “and I don’t think it’s just because he’s a member of the House.”

O’Rourke could be a different story. Thanks to his close race against Cruz in a deep-red state, he has national name recognition and a national fundraising network. “He’s unique, because he does already have this enormous grassroots fundraising energy and excitement,” Mike Lux, a Democratic strategist, said in an interview. “That puts him in a very different place than a John Delaney or an Eric Swalwell.” Having given up his seat to challenge Cruz, O’Rourke also would have more than enough time to devote to a presidential bid.

If O’Rourke ran for president and won, he would defy history. But the political environment in America today doesn’t adhere to the conventional wisdom. “I think you need to be a cultural phenomenon in order to win the presidency in the twenty-first century,” Spain said. “And Beto clearly has that.” And if a vulgar reality TV star with no political or military experience can win the White House, it would seem downright ordinary for the next president to be a retired Democratic congressman from Texas.

The popular perception of Brexiteers as

lacking a rational vision—as being motivated, rather, by naïve and nostalgic

fantasies—is widespread. In November, the London

Times published an illustrative cartoon. Comprising three panels, it shows

an angry mob of Brexiteers, leading Conservative MPs Boris Johnson and Jacob

Rees-Mogg at the fore, chanting: “What do we want?!” Then silence and

bewildered glances. Then: “NOW!”

After Prime Minister Theresa May’s proposed Brexit deal collapsed early last week—it was pulled from Parliament at the final moment because she didn’t have the votes—the perception has taken on new force. Two and a half years after the referendum, the British cannot agree on what they want from Brexit, even—or especially—those who wanted it most. Suddenly, with the deadline for negotiations with the European Union looming on March 29, 2019, “Brexit means Brexit” is no longer an adequate answer.

Having survived a confidence vote, May returned to Brussels on Thursday to renegotiate her deal—the culmination of over a year’s work, which she initially insisted was impossible to improve. Questions over Britain’s intentions returned to the surface. “Our British friends need to say what they want instead of asking us to say what we want,” European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said. In a private meeting, German Chancellor Angela Merkel reportedly interrupted May to tell her the same thing. “What else do you want?” Merkel asked.

But Britain’s most ardent Brexiteers know exactly what they want, even if political constraints make it hard to achieve. Their aims are well-defined and, for all Brexit’s parochial connotations, their ambition is global. Funding networks linking libertarian think tanks in America—such as those funded by the Mercer family and the Koch brothers—to Brexit have been exposed over recent months, and the interest of President Donald Trump and his ex-strategist Steve Bannon, along with the upper echelons of Europe’s far-right, is plain to see.

The result they are agitating for is a so-called “hard Brexit”—cutting all ties with the EU, whether through a “no deal,” in which negotiations fail and Britain leaves by default on deadline day, or through some kind of deal, which would simply give Britain more time to adjust to the same stark scenario. The forecasts for this outcome are bleak, particularly for a no deal, but it has attracted an array of enthusiastic and influential supporters within Britain: Boris Johnson, Jacob Rees-Mogg, former Brexit Secretary David Davis, Trade Secretary Liam Fox, ex-UKIP leader Nigel Farage, and former leader of Vote Leave, Conservative MEP Daniel Hannan. Where others see a gathering storm, they see only a bright new world waiting on the other side, dizzy with possibility.

A web of wealthy think tanks, lobbying groups, and organizations that seem to blur the line between such distinctions are behind them. These individuals and organizations are bound by a shared dream of deregulating the British economy and opening it up to U.S. markets—billed as the “Brexit prize.” In this vision, Britain escapes the EU to become a free-market idyll, shorn of all EU regulations—a nation at once enclosed in a historical sovereignty and exposed to all the market forces of a globalized world.

It’s a contradictory vision that, in many ways, strikes at the heart of modern conservatism the world over. A hallowed heartland is idolized, only to let big business hollow it out. The fight to “free” Britain from the EU is framed as the latest round in Britain’s historic rivalry with the continent. With the rhetoric of war and the “will of the British people,” a staunchly libertarian agenda of slashing the British state can be pursued as a patriotic mission to save it.

And so, for Britain’s most ardent Brexiteers, the closer their cause comes to completion, the greater the betrayal becomes. Johnson accuses the European Union, and the supposedly treacherous Theresa May, of wanting to make Britain “a colony.” Whenever May tries to soften their Brexit stance, aware of the economic shock their dramatic rupture would entail, they accuse her of “surrender” and of “waving the white flag.” Against an adversary like the EU (also Britain’s major trade partner), they argue, only the hardest of Brexits will do: Britain must be excised from all EU institutions, rules, and regulations completely. They have vowed to battle May with “trench warfare” and say that they are ready to watch her, in the words of one Conservative MP, “bleed out slowly.”

The main proponents of a hard Brexit are radical free-market Conservatives with a history of trans-Atlantic ties. A recent blueprint for a future U.K.-U.S. trade policy post-Brexit shined a light on the shared interests their project entails. The proposal listed as contributors a nexus of British and American libertarian organizations and received glowing endorsements from Brexit’s most influential figures. Its three authors were Daniel Hannan and two employees from the Cato Institute.

Among other suggestions, the blueprint advocated opening up Britain’s public services—including education, legal services, and, eventually, health care—to U.S. competition. Current EU regulations that prevent certain U.S. products from entering the British marketplace—particularly rules governing food hygiene and environmental standards—should be discarded, it argued, along with the EU’s relatively progressive policies on workers’ rights.

May’s proposed deal is opposed on both sides of the Atlantic precisely because it makes such a deal impossible. Under May’s plan, Britain remains tied to the EU’s regulatory system, and the barriers to U.S. trade persist. Britain loses its power to influence the regulatory system (hence the “colony” accusation), yet gains control of its borders—for so long, Brexit’s raison d’etre.

May still sees strong borders as the priority. As leader of the Home Office from 2010 to 2016, she championed this cause with the cruel confidence and creativity that, in the eyes of her Conservative critics, her current leadership lacks. More recently, when the EU and Britain drew up a document regarding their future relationship, May personally insisted that “the ending of the free movement of people” be placed on the first page.

What’s clear from the opposition to May’s deal, however, is that for all the xenophobia incited during the referendum by the Leave campaign, border control was not the highest goal. Even Nigel Farage, whose sole concern seemed to be Britain taking back control of its borders, is unenthused by May’s deal. Many other leading Brexiteers, including its main financial donors, have said that it would be better to remain inside the EU than leave on May’s terms. Clearly, for the parties most invested in Brexit, the real reasons for leaving lie elsewhere.

The sad, unsolvable riddle at the heart of British politics is that, while May’s deal is doomed, every other deal is too. There is simply no resolution to Brexit that can claim a majority in Parliament. The divisions are too deep, and the costs too steep for compromise. Britain is left lurching between three dramatic scenarios: a second referendum, a general election, and a no deal Brexit.

There is no guarantee that either of the first two scenarios will resolve the Brexit impasse. A no deal outcome, by contrast, definitely will—it is the hard Brexit par excellence—and the consequences could be severe. This is what will happen: At 11pm Greenwich Mean Time on Friday, March 29, 2019, Britain will leave the EU without any new arrangement in place. Its membership, along with 45 years of legal and institutional integration, will become void in an instant, leaving almost everything in limbo.

According to almost every analysis, it is by far the worst of any outcome for the British economy. The uncertainty would be unprecedented; the value of the pound would plummet. Grocery stores and pharmaceutical companies have started stockpiling essential materials to prepare for havoc at the border. But in its superficial speed and simplicity—overnight, the Brexit prize is brought home and EU regulations disappear—it stands as a satisfying solution for many Brexiteers.

Until recently, May always said that “no deal is better than a bad deal.” For the Brexiteers, however, even more indifferent to the dangers, there may be no deal better than a no deal. Anything else leaves Britain tied, in some unacceptable way, to Brussels, only now with a reduced say and a £37 billion divorce bill to pay. Chaos is preferred to such concessions and, in the end, may even be more fitting for the main event: Britain’s day of liberation.

Besides, the national fantasy, indulged by most Tories, that Brits are at their best when their backs are against the wall, gives any hardship a patriotic spin. At the Conservative Party Conference, Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt invoked the “Dunkirk Spirit” to warn the EU of who and what they were up against. Over the weekend, Hunt declared that Britain would “flourish and prosper” in the event of a no deal.

So even if a no deal Brexit happens exactly as the worst predictions warn, Britain can still celebrate. Brexiteers will take solace in the great spirit of British sacrifice, a sacrifice none of which will have been theirs. The queues at customs can perversely prove that Britain has taken back control of its borders, even if it is only capital that is set free. After World War II, it was sometimes joked that the British gave up rationing only reluctantly. Now, as the distant possibility of rationing returns to Britain’s streets—the government recently appointed a new “Minister of Food Supplies” to cope with potential food shortages—that dormant Dunkirk spirit can be revived. Britain just needs to keep calm and carry on.

No comments :

Post a Comment