It would be an understatement to say that Big Tech had a very bad 2018. This was the year of Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, and Sundar Pichai raising their right hands before Congress. It was the year that Cambridge Analytica became a household name, and the year that social media was implicated not only in data misuse and election interference, but ethnic cleansing. Perhaps above all, this was the year that Big Tech lost its luster, when Google, Facebook, Amazon, and others finally came under widespread scrutiny—from the press, politicians, and the broader public alike.

And 2018 isn’t even over yet, much to Facebook’s chagrin. The New York Times delivered another shock on Tuesday, reporting that the company gave Microsoft, Spotify, Netflix, Yahoo, and some of the other biggest tech companies in the world “more intrusive access to users’ personal data than it has disclosed, effectively exempting those business partners from its usual privacy rules.” Facebook even allowed Netflix and Spotify to read its users’ private messages. On Wednesday, news broke that D.C.’s attorney general is suing Facebook over Cambridge Analytica scandal.

Despite all this, 2018 could have been an even worse year for Big Tech. The idea of reining in the Silicon Valley giants has only slowly gained momentum in Washington, and signs point to modest regulations. No one on Capitol Hill is really talking about breaking up Facebook or Google or Amazon, who are spending millions on lobbying to ensure that they have significant input in whatever Congress cooks up. And although tech companies are taking election interference more seriously, it’s believed that most of the major players—principally Russia—sat out the 2018 midterms. The post-2016 electoral system remains largely untested.

That’s fortunate, because it has become increasingly clear that the U.S. is at least as vulnerable today as it was then. While Congress and tech companies have been busy conducting autopsies of the 2016 election, they have been slow to address the problems exposed by foreign interference. Meanwhile, intelligence operatives in Russia and other countries have been developing new influence tactics. And America’s voting infrastructure remains just as antiquated as it was two years ago.

So perhaps it’s an understatement to say that the U.S. is equally vulnerable today. As bad as things were in 2016—as bad as they are now—it looks like they will only get worse.

Two new reports shared with the Senate Intelligence Committee found that Russian intelligence operatives reached millions of Facebook users between 2013 and 2017 in an effort to exploit social, racial, and political tensions. The Russian Internet Research Agency recruited unwitting “assets” to spread misinformation and targeted black Americans. “The most prolific IRA efforts on Facebook and Instagram specially targeted Black American communities and appear to have been focused on developing Black audiences and recruiting Black Americans as assets,” one report states. Researchers also found a vast operation designed at inflaming conflict: Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, Tumblr, Pinterest, Medium, YouTube, Vine, and even Google+, among others, were all targeted by Russia.

On Tuesday, Facebook’s embattled CFO, Sheryl Sandberg, addressed the reports. “Facebook is committed to working with leading U.S. civil rights organizations to strengthen and advance civil rights on our service,” Sandberg wrote on her Facebook page. “They’ve raised a number of important concerns, and I’m grateful for their candor and guidance. We know that we need to do more: to listen, look deeper and take action to respect fundamental rights.”

As the scope of Russian involvement in the 2016 election has become clear, companies like Facebook and Twitter have taken some action, purging accounts tied to intelligence operations and investing in artificial intelligence to root out bad actors. In September, Zuckerberg posted a 3,300 word blog post on Facebook detailing the steps Facebook has taken to prevent election interference, including the promise to hire 10,000 new employees to monitor safety and security concerns. Facebook and Twitter, in particular, have used enforcement as a PR operation, with large-scale content and account purges being misleadingly touted as anti-Russian efforts. But they have also disclosed influence campaigns from countries not believed to have been involved in the 2016 elections, such as China and Iran.

While lawmakers have been slow to act, the government has also taken some steps to limit interference. This past year, the Department of Homeland Security worked with state election commissions to secure voting rolls and machines. The Department of Justice and other intelligence agencies have taken a more active and public approach to monitoring social networks.

It’s likely that a number of powers will seek to influence the 2020 election, given the chaos that Russia was able to cause. In August, Facebook found a number of ongoing influence campaigns that were seeking to wreak havoc globally. “Unlike past influence operations on the social network, which largely targeted Americans, the fake accounts, pages and groups were this time also aimed at people in Latin America, Britain and the Middle East,” The New York Times reported. For all the focus on American elections, it’s clear that influence campaigns like the one undertaken in 2016 will become a factor in nearly every major election going forward, regardless of where it’s taking place. “The 2016 election was the Pearl Harbor of the social media age,” The New York Times’ Kevin Roose recently wrote, “a singular act of aggression that ushered in an era of extended conflict.”

Amid scrutiny from the U.S., influence campaigns have only grown more sophisticated. “Russia’s attacks did not stop after Trump’s election, but they have continued to evolve and adapt,” he wrote. “Russians appear to have shifted their focus away from Facebook, where a team of trained specialists now prowls for influence operations, and toward Instagram, another Facebook-owned app that has flown under the radar. The Internet Research Agency appears to have largely sat out the 2018 midterm elections, but it is likely already trying to influence the 2020 presidential election, in ways social media companies may not yet understand or be prepared for.” This may be good news for Facebook, but it just means that the efforts to influence elections have become more diffuse and diverse, and will likely be more difficult to identify and contain going forward.

Thanks in part to the fact that Republicans have controlled both houses of Congress for the past two years, the country remains woefully unprepared for further electoral influence campaigns. With Republicans focused on protecting the president—and on trivial questions, like non-existent censorship—and too many Democrats with close ties to big tech, Congress has been unable to agree on even a basic approach to regulation. Old, computerized voting machines run on outdated software that is vulnerable to hacking. Despite some efforts—notably the Honest Ads Act, which would require tech companies to disclose the identities of people paying for political ads—Congress has made no progress when it comes to requiring companies like Google and Facebook to be more transparent. But even that bill, which was sponsored by two Democrats and one Republican, has not been greeted with much enthusiasm on Capitol Hill, thanks in part to aggressive lobbying by Facebook.

The tech giants, like any corporation, are beholden to their bottom lines and will only do the bare minimum to prevent abuse. The business plan of a company like Facebook, which is dependent on monetizing user data, provides perverse incentives to do the bare minimum when it comes to protecting elections. While a Democratic House can be counted on to push for more robust enforcement and protections, Congress remains divided and the Trump administration has been unwilling to do much of anything to address the issue. We’re just months away from an influx of candidates for the Democratic nomination, which means we’re just months away from an onslaught of electoral influence operations. Time is running out.

In February, gunmen burst into the home of an investigative reporter in Slovakia and fatally shot him in the chest. In April, ISIS suicide bombers targeted the press corps in Kabul, killing nine people in a single attack. In June, a disgruntled reader entered the newsroom of the Capital Gazette in Maryland and gunned down four journalists and a sales assistant. And in October, Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post contributor and Saudi exile, was murdered and dismembered by government agents in the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul.

All told, at least 34 journalists were murdered in 2018, an 89 percent increase over the previous year. The number of journalists in jail is also at record highs—251 by the most recent count. Together, these statistics tell a damning story about the current era, the worst in recent history in which to be a reporter.

Journalists who take on powerful interests have always faced dangers. But even war reporters were once protected by the symbiotic relationship they had with those they covered. If guerrilla fighters or rogue governments wanted to communicate with the world, they had to talk to the press. Killing journalists, quite simply, undermined their ability to get their message out. That dynamic changed with the advent of the internet. By the mid-2000s, Mexican drug cartels had become savvy online users, as had terrorist networks like Al Qaeda. A decade later, the Islamic State developed an even more sophisticated communications operation, with sharp social media strategies, slickly produced YouTube videos, and even a glossy magazine, Dabiq, which published stories outlining the religious arguments for slavery and urging Muslims in the West to join the fight in the Levant. The group almost never interacted with journalists, except when they appeared as props in their elaborately staged execution videos. As governments have pushed ISIS back from its Syrian stronghold, the attacks the group once launched on journalists have become less frequent. Organized crime networks like the Mexican cartels and the European mafia are now the growing threat. And sometimes, as with Khashoggi, a state murders one of its own.

There is no single explanation for why journalists are being killed and imprisoned. But the disappointing response of the United States government to these crimes—its abrogation of its traditional role as model for a free press—helps explain why the perpetrators are acting with such impunity.

There was a time, not that long ago, when the White House acted when a journalist was killed abroad. In 2002, the Bush administration pressured Pakistani authorities to bring Al Qaeda operatives who’d killed Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl to justice. Omar Sheikh, a key figure in the murder and a British national, was convicted in a Pakistani court that year and remains in prison. When Russian investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya was murdered in the entryway of her Moscow apartment building in October 2006, President George W. Bush personally phoned Vladimir Putin to express his dismay. The Obama administration kept up the pressure, raising the killing of journalists with Russian officials and sending diplomats to monitor the murder trials.

President Donald Trump has changed course. He spends more of his energy attacking journalists than he does defending their rights. His lack of concern for their fate was first apparent when MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough asked him in 2016 about journalists being murdered in Russia. “Our country does plenty of killing, too,” Trump said. Perhaps the most telling recent example of the president’s attitude is his remark about whether Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman knew about Khashoggi’s murder. “Maybe he did and maybe he didn’t!” he said, a comment that appears in the official White House statement, which goes on to call Saudi Arabia “a great ally in our very important fight against Iran” and the United States its “steadfast partner.”

Repressive leaders around the world are using Trump’s tactics. After President Trump called CNN and The New York Times “fake news,” the president of the Philippines used the same language to describe the Filipino news web site Rappler, which has exposed corruption in the Duterte government. Maria Ressa, Rappler’s editor, pointed out that when Trump rescinded the accreditation of CNN’s Jim Acosta, he was mimicking President Duterte’s actions earlier in the year with a Filipino reporter. Many other countries, such as Egypt, Russia, and Singapore, have embraced the term “fake news” and used it to justify restrictions on the media. In fact, the number of journalists imprisoned on charges of publishing “false news” (the term tracked by the Committee to Protect Journalists, the organization I lead) has more than tripled since Trump took office, from nine to 28.

A new generation of populist leaders now define themselves in opposition to the media. They attack their own journalists and are largely indifferent to the fate of reporters in the rest of the world. This attitude has consequences, or rather prevents consequences for people who deserve them. More than 85 percent of murders of journalists go unpunished, according to the 2018 Impunity Index, which was compiled by the CPJ. The key to fighting impunity is international pressure. And it’s been sorely lacking. Journalists face new forms of violence and repression, and, for now at least, few leaders, certainly not Donald Trump, are willing to stand up and defend them.

In Kinshasa’s Saint Joseph parish on an August afternoon, a crowd gathered to give thanks: The man they had risked their lives to oust was stepping down from the presidency.

Just a week earlier, President Joseph Kabila, who has ruled the Democratic Republic of Congo for nearly 18 years, enriching himself and his family on the country’s vast natural resources, had announced he would not be standing for re-election in December. Those filling the wooden pews were one of the reasons why. Seated side by side were four of the Catholic lay leaders who organized the demonstrations many of the worshippers had participated in. Hunted by authorities for months, they came out of hiding for a service of thanksgiving—and to plot the road ahead.

Isidore Ndaywel, seated with fellow activist parishioners of St. Joseph Matonge Catholic Church.

Isidore Ndaywel, seated with fellow activist parishioners of St. Joseph Matonge Catholic Church.“We still have a lot to do,” their lay leader Isidore Ndaywel, a professor, urged from the pulpit following communion. In a checkered shirt and horn-rimmed glasses, he projected a mild air, but his voice boomed over the speakers. “We have to consolidate this victory with vigilance, with transparent, inclusive, and credible elections. Even if we have won this battle, this is just the first stage of the fight. In this country, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, we want the future to be different than the past.”

Congo has not seen a peaceful or democratic transition of power since it gained independence from Belgium in 1960. Under Kabila, the country has endured years of armed conflict and humanitarian crisis, its citizens among the poorest in the world. And since 2016, when Kabila disregarded the constitutional term limits that should have brought his regime to an end, a coalition of activists has been fighting for democratic norms, led by what elsewhere would seem an unexpected institution: the Catholic Church. Having won a spectacular victory in August with Kabila’s concession, those activists now face a new test—as Ndaywel predicted at the service. On December 23, DRC is scheduled to hold elections. Kabila’s chosen successor, former interior minister Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, oversaw a bloody crackdown on the Catholic-organized protests. To the opposition, he represents a continuation of Kabila’s corruption and oppression. They fear the vote will not be a fair contest.

``` ```A choir sings during mass in Kinshasa, where the Catholic Church has become one of the country’s few effective institutions.Since the country’s first prime minister was deposed and killed with U.S. and Belgian support shortly after independence, the DRC has suffered from a series of plunderous dictators. Mobutu Sese Seko, a kleptocratic ruler who enjoyed strong Western support as he changed the country’s name to Zaire and implemented one-party rule, brought the nation close to bankruptcy during nearly four decades in power. The current president’s father, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, overthrew Mobutu in 1997, but didn’t usher in stability. Another war soon broke out, drawing in the entire region and killing millions through violence, starvation, and disease. In 2001, the elder Kabila was assassinated. His son Joseph, then just 29, took his place, winning elections twice, though the second vote was marred by allegations of fraud. But while the war officially ended in 2003, fighting continues, with dozens of rebel groups operating in the country and millions suffering from the violence. Conflict has hampered efforts to contain a worsening Ebola outbreak in the country’s east.

In an increasingly dysfunctional state crippled by corruption and conflict, the Catholic Church has become one of the country’s few effective institutions. Nearly half of the DRC’s population of 80 million is Catholic, and the Church provides education and healthcare to millions. It has also long played a political role. In the twilight of Mobutu’s regime in the 1990s, Church leaders participated in efforts to reform the government and chart a path toward a democratic transition. When Mobutu resisted, a group of Catholic activists known as the Lay Coordination Committee (known by the French acronym CLC) organized a massive protest in support of reform, assembling at the same St. Joseph parish where the group gathered in August. The army attacked that protest, killing dozens.

Survivors of a Catholic activist killed in protests on December 31, 2017. At least 18 people were killed in demonstrations over three months calling for the end of President Joseph Kabila’s rule. John Wessels/AFP/Getty

Survivors of a Catholic activist killed in protests on December 31, 2017. At least 18 people were killed in demonstrations over three months calling for the end of President Joseph Kabila’s rule. John Wessels/AFP/GettyIn late 2016, the country’s conference of bishops negotiated a deal between Kabila and the opposition, known as the St. Sylvester Accord, in which the president agreed to hold a vote to choose his successor by December 2017. That election never happened. In response, Catholic activists resurrected the CLC and called for nationwide protests against Kabila’s power grab. Thousands of the faithful answered the call in three protests in December 2017, January 2018, and February 2018, spilling out of parishes from Kinshasa to Goma after services and taking to the streets. Security forces met them with tear gas and bullets, killing at least 18 people and wounding dozens more. But the pressure worked, protests within and strong diplomatic pressure from without leading to Kabila’s August announcement.

In some places, such explicit political intervention by a religious institution would draw cries of protest. For Father Joseph Musubao, an assistant priest at St. François de Sales parish in Kinshasa, however, it is the Church’s duty to oppose a regime that is causing God’s people to suffer. During his January 21 homily ahead of the second of the CLC’s three protests, he told his congregation that the church had three tasks: to announce the good news of the gospel, to denounce evil, and to reject corrupt powers. In the eyes of the round-faced priest, that mission didn’t just justify the protests, but nearly compelled Christians to take part. “They have to put into practice the gospel we are preaching to them,” he told me, “the gospel which says that a person created by God should live happily on this earth, and that the wealth and resources that God has given to every nation should be shared equally and should not belong to a minority that takes millions of people hostage.”

Father Joseph Musubao called on his parishioners to participate in the January 2018 street protests, which were attacked by armed police.

Father Joseph Musubao called on his parishioners to participate in the January 2018 street protests, which were attacked by armed police.Despite the violent crackdown on a protest weeks earlier, at least a thousand people gathered in the parish yard after his sermon, singing as they marched out the gate. They made it no further than the steps, Musubao told me, when the police stationed outside fired a volley of tear gas. The crowd retreated into the parish compound, but soon a police vehicle appeared at the gate, and an officer leapt to the gun mounted on top. He fired into the crowd. The bullets struck Thérèse Dechade Kapangala, an aspiring nun and Musubao’s niece. She died instantly.

Musubao spent nearly three weeks trying to retrieve her body from a government morgue, where officials were loathe to release evidence of a government crime. Musubao no longer lives at home or preaches in his parish, due to threats, but he still believes in the cause: “We don’t have the right to abandon God’s people in their problems,” he said. “If we do, we will be bad shepherds.”

The government contends that the Church is serving the interests of foreign powers who want to exploit Congo’s resources and its people. “Some of them are, you know, agents of some influence groups abroad. Those who were colonial agents, now they are becoming … agents of neo-colonial powers,” Minister of Communication Lambert Mende told me, referring to the Church’s historic cooperation with Belgian colonizers. “If they want to gain influence, let them remove their status of bishops, and become politicians. And we [will] run together and we shall see who will win elections.”

In early December, the European Union renewed sanctions imposed on Shadary, Kabila’s chosen successor, for serious human rights violations. A loyalist with little support of his own, Shadary’s election would likely allow Kabila to maintain power, possibly until another presidential run in 2023, since DRC only limits consecutive terms. In recent interviews, Kabila refused to rule out another run.

The CLC, many of whose members continue to live in hiding, has not called a protest since February. Some pro-democracy activists have criticized the choice. There has been disagreement within the CLC itself, as well.

One of many banners and billboards bearing the image of President Joseph Kabila found in the capital Kinshasa. Kabila’s term was supposed to end in 2016.

One of many banners and billboards bearing the image of President Joseph Kabila found in the capital Kinshasa. Kabila’s term was supposed to end in 2016.Leonie Kandolo, one of two members who have since split from the eight-person committee, was unable to attend her brother’s funeral due to threats to her safety, and hasn’t seen her children all year. She would like to see more action, and more collaboration with pro-democracy activists. “Since April, May, till today, what kind of action have they taken?” An election, without real change, is not enough, she said. “We have to reach the level of changing the system. We have to uproot the system.”

An agreement among opposition parties to unite behind a single candidate collapsed almost before the ink was dry, and two opposition figures are now facing off against each other. Shadary, meanwhile, is making transparent appeals to Catholic voters. He kicked off the official campaign period by attending Mass in Kinshasa’s Notre Dame Cathedral on November 24, and used an image of Pope Francis on a campaign poster that described Shadary as a “practicing Catholic.”

Opposition parties and activists want the election commission to cancel the planned use of electronic voting machines on December 23, which they fear will make it easier for the government to rig the vote or will cause technical difficulties that will mar the election. They also decry irregularities in the voter roll, the disqualification of two of the strongest opposition candidates, and continuing deadly crackdowns on protests and even on campaign events. Security forces killed at least seven opposition supporters, wounded 50, and arrested dozens more while dispersing opposition campaign events earlier this month, sometimes with live ammunition and tear gas. The opposition is pressing ahead with the vote.

The Church, having pressed Kabila to hold elections, was loath to then suggest a delay in the electoral calendar. But in addition to a cautionary statement from Congo’s national bishops’ conference in November, urging the country to “avoid a parody of an election,” the Church is sending thousands of election observers to watch for problems at the polls, and CLC members say they are determined to keep up the fight for real change, whatever it takes.

Activist Gertrude Ekombe speaks to fellow members during a meeting of the Lay Coordination Committee (CLC) outside Parish of Saint Joseph Matonge Catholic church in Kinshasa.

Activist Gertrude Ekombe speaks to fellow members during a meeting of the Lay Coordination Committee (CLC) outside Parish of Saint Joseph Matonge Catholic church in Kinshasa. CLC member Gertrude Ekombe has not gone home or to work since January. She and the others are tired, under financial pressure, and missing their families. “Sometimes you get discouraged when you get phone calls from your kids saying they’ve seen suspicious people around the compound,” she said in August. But if the election is not fair, “we’ll keep on doing protests. If we have to die, we are ready to die.”

The International Women’s Media Foundation supported both the reporting and photography for this story as part of its African Great Lakes Reporting Initiative.

When we say that a movie or a book “romanticizes” a harmful activity, we usually mean that it irresponsibly makes drug use or violence seem like something that the viewer might also like to do. Trainspotting or Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, for example, show booze and drugs as interesting and cool (Leaving Las Vegas, less so). But romanticization also has another meaning. The word comes from the Old French, and before it became about love or sublimity, a romance was a story in verse (roman still means novel in French).

Storytelling and romanticism are closely linked—sisters in narrative, if you will. Art that is about suffering is always at risk of romanticizing that suffering, because the act of telling a story imposes beginnings and middles and ends, not to mention stirring soundtracks, upon experiences that in real life have no such punctuation. To make a movie about drugs almost guarantees that you romanticize them, because otherwise there would be no narrative at all—just long nights, empty bank accounts, and a feeling like cold hunger.

Two new movies about white teenagers addicted to drugs, as well as the parents who struggle to keep them upright, labor to overcome this inherent tension. Ben Is Back stars Julia Roberts as mom Holly, whose son Ben returns home for Christmas on an ill-advised visit from rehab for his opioid addiction. The movie follows one wild Christmas Eve, as the consequences of Ben’s previous actions come back to haunt him. Holly has to chase him across town as he makes a series of very bad decisions.

Beautiful Boy is also about a son and a parent. Timothée Chalamet is Nic, and Steve Carell is his father David. Where Ben Is Back is set in cold New York state, Beautiful Boy is a story of sunny, Californian addiction. One features a mom, the other a dad. But the movies follow the same basic arc: white son wrenches away from a loving family and into serious addiction. What can a parent do in the face of this affliction? And where do they draw the painful lines in the sand when the children go too far? The sons just keep screwing up, and nobody knows what to do.

Beautiful Boy is a much easier movie to watch, but Ben Is Back is much the better film. The former is drenched in golden sunshine, lily-white in its cast. It depicts Nic as a baby for whom hope is never quite lost. The latter is about a coddled white teenager, but at least his stepfather (the capable Courtney B. Vance) gets to say that, if Ben were black, he’d have been incarcerated long ago.

The movie’s real achievement lies in Roberts’s performance, which is possibly her best. Holly is incandescent with worry. She’s good and kind and intimate, but with the oppressive weight of, well, a mother. The movie does an excellent job of evoking the texture of home: the familiarity, the remains of old versions of yourself, the heavy love that can feel like mustard gas.

If there’s a valuable message to these movies—apart from the fact that addiction sucks, and it’s very hard to get out of, but there’s a reason people do drugs—it’s in that depiction of home. Both these boys are loved fiercely by their families, but for some people being loved just doesn’t feel good.

The movie industry has taken other approaches to this issue. The 2017 documentary Heroin(e) follows three women—a firefighter, a judge, a volunteer—battling the scourge of opioid addiction in West Virginia. And in the internet age, audiences have other means of seeing what drug abuse looks like. Last week, The New York Times ran a piece about opioid addicts who have been filmed overdosing in public and put on YouTube or the news. One woman nicknamed the “Dollar Store Junkie” was filmed unconscious beside her frantic two-year-old daughter. She said, “I know what I did, and I can’t change it. ... I live with that guilt every single day.”

Both the documentary and the piece raise our awareness of how we perceive addiction. One conclusion a lot of people have reached is that this country has suddenly started to care about drug addiction because opioid abuse in America largely affects white people—people who begin with a legitimate Percocet prescription and end up dead from heroin overdose. As an American Journal of Public Health article puts it, the authorities’ reaction to this new crisis couldn’t be more different from their responses to drug issues in other communities: “In the context of public concern that White Americans are turning to heroin, policymakers are calling for reduced sentencing for nonviolent illicit drug offenses and the expansion of access to addiction treatment. At the same time, in Black and Latino communities, many drug-addicted individuals continue to be incarcerated rather than treated for their addiction.”

The relevant critique of the entertainment industry makes itself. We didn’t get this kind of sensitive, detailed portrayal of crack cocaine addiction in black communities in the 1990s, even as (or maybe because) the Clintons fueled white nightmares with visions of drug-addled superpredators. We got Crackheads Gone Wild and Cops. Beautiful Boy and Ben Is Back would never have been made if white Americans didn’t all of a sudden care about substance abuse—because it affects them now.

That critique doesn’t just have to be a political call-out; it’s also a way into reading these movies as pieces of art. It goes back to the idea of what it means to romanticize something. It doesn’t just mean that the subject matter goes from bad to good. To romanticize drug abuse can be as straightforward as applying traditional moviemaking narrative structures to the topic.

Both movies struggle with the fact that sobriety and relapse go in circles, which is bad for storytelling. Ben Is Back gets around the problem by setting its action in one night; Beautiful Boy settles for a flashback-riddled exploration of family dynamics. But turning a drug addict into a handsome young man with good skin and a ton of potential to waste—that’s easy. All you do is cast a pretty guy and let him cry onscreen in his mother’s arms, maybe give him some poetry to read aloud. (Nic does Bukowski, and I’m not even joking.) Sprinkle a little hope on him at the end and you’ve got yourself a tragic hero.

That’s a problem, because being addicted to drugs in 2018 means bystanders filming you passed out in a dollar store. Of course there are plenty of beloved, middle-class people who have the struggles of Ben and Nic, and their suffering cannot be denied. But in defense of sheer reality, there are a lot more addicts who can’t afford dentistry and look unattractive because of it. These are people whom you might cross the street to avoid. Homelessness isn’t Timothée Chalamet draped handsomely across a diner; it’s contemptuous glances and shame. The women and men of Heroin(e) have universally bad skin and radiate that specific narcotic waxiness that comes from long-term abuse, because that’s what it looks like. In short, drug addiction is usually a story about poverty, inflected by race, and these movies are looking in the totally opposite direction.

There’s no story to addiction—no beginning and no end, unless you count birth and death. If you have substance abuse problems, then you know that the problem does not exist externally to your personality: it is coextensive with your interpretation of the world. To be addicted to a substance is to feel a sensation as boring, all-consuming, and impossible to describe as thirst. That’s all. And how can you make a movie about that? It’s difficult, so directors are using drugs as a starting point to make cinema about families, social politics, and love—not exactly groundbreaking.

Neither Ben Is Back nor Beautiful Boy can truly claim to be movies about drugs. They’re just regular old romantic exile plots that happen to feature drugs in a supporting role. If Hollywood is going to start hacking out these tales of white pain, then filmmakers need to develop some much sharper tools.

Karina Longworth’s long-running podcast about classic movies, You Must Remember This, sets out to tell the “secret, and/or forgotten history” of Hollywood in its much-mythologized golden age. Her new book, Seduction, offers an insistent, clear-eyed reminder of the fact that history does not get buried or forgotten by accident, but by design, in order to burnish and elevate the reputations of powerful men, and to cut women down to size.

SEDUCTION: SEX, LIES, AND STARDOM IN HOWARD HUGHES’S HOLLYWOOD by Karina Longworth Custom House, 560 pp., $29.99

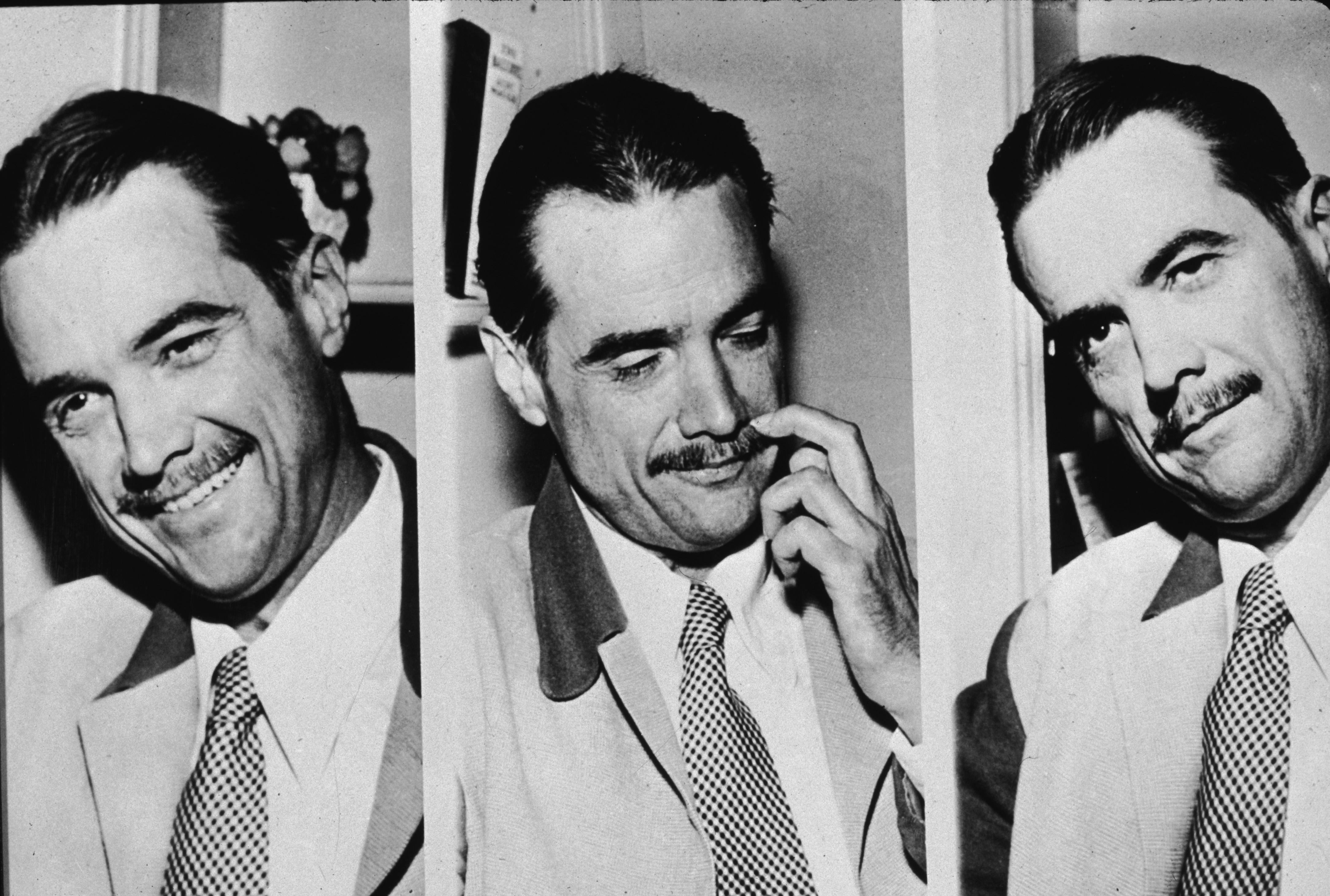

SEDUCTION: SEX, LIES, AND STARDOM IN HOWARD HUGHES’S HOLLYWOOD by Karina Longworth Custom House, 560 pp., $29.99It may seem surprising, at first, that Longworth’s central subject in this book is a powerful man: Howard Hughes, who dominated American culture in the middle of the 20th century, defining and embodying what it meant to be a millionaire, a mogul, and a madman. Born in Houston in 1905, Hughes lost both of his parents in his late teens and inherited the family business, which manufactured the drill bits needed to cut through the earth to get to oil. Before he was 20 he had strong-armed his grandfather and other relatives out of the company, gotten himself declared a legal adult, married a Houston heiress, and decamped for Hollywood, where he set himself up as a producer-director.

His obsessions at the time were golf, aviation, movies, and money—eventually, women would replace the golf. For the next 30 years he occupied a unique position in American culture. He was a perennial outsider in the movie business, who undertook wildly ambitious feats of engineering, filmmaking, and flying, and was paired with all the most beautiful women in Hollywood. Cushioned by his wealth, he was eventually brought down not by his enemies but by his own inner demons.

If modern readers know much of Hughes’s story, it is likely through Martin Scorsese’s visually inventive and emotionally shallow 2004 biopic The Aviator. Leonardo DiCaprio plays Hughes as a nervy milquetoast whose problems stem from the erotically-charged dominance of his mother. The film minimizes Hughes’s aggressive, transactional, and compulsive womanizing, and instead implies that he was at heart a one-woman man—that woman being Cate Blanchett’s cartoonishly swaggering Katharine Hepburn. Hughes’s interactions with women are supposed to demonstrate the hypnotic power of the man and his money—as when he propositions a cigarette girl in a nightclub. We’re given to understand that this is just how Hollywood works.

Longworth’s story of Hughes and the world he built and controlled is a lot more complex. It illustrates the many ways in which the Texan outsider did not conform to Hollywood’s values. It has the pace and intensity of a true crime story, which in a way it is. Longworth downplays the legendary weirdness of her subject and emphasizes the ways he gamed a system set up to work for him. Instead of focusing on Hughes as the hero (or anti-hero), as most Hollywood histories have tended to, she instead seeks out the stories of the women who lived and worked in the riptide of his influence. By unearthing unpublished material from the archives of Hughes and his contemporaries, and, more often, by astutely reading between the lines of official histories, Longworth shows how valuable and revealing it is to tell the story of a playboy from the perspective of his toys.

The book opens with an account of a party one night in 1925 at the Cocoanut Grove, the lavish nightclub inside Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel. Frederica Sagor, a screenwriter in her mid-twenties, witnessed the events and described them in a candid memoir of her early career, published in 1999 shortly before she turned 100. Sagor recalled watching as her “drunk, drunk, drunk,” half-undressed middle-aged bosses pawed at young women hired or lured for the evening, yet she showed little sympathy for the women who allowed themselves to be traded hand to hand like poker chips. The men were acting as men would always act. But if a woman wanted to be anything more than “a call girl—half naked, lying across a chair, her hand stretched out to receive a hundred-dollar bill,” then it was up to her to resist, Sagor thought.

Longworth uses Sagor’s story to kick off a much larger investigation into the colossal power imbalance between men and women in Hollywood—which persists to this day—and to show how hard it was for any woman, within that system, “to sell something other than her body to Hollywood’s men.” This was marginally easier in the early days, before the Hollywood star-making system was established, run and regulated by men. In the early silent era, women like Lois Weber could write and direct their own stories about the state of the world and the place of women within it. But by 1933, when fifteen-year-old British actress Ida Lupino arrived in Hollywood, there was already an established version of every kind of on-screen woman one could be. Lupino began as a new Jean Harlow, the bleach-blonde star of Howard Hughes’s World War I melodrama Hell’s Angels. She soon tired of that game and tried actually acting, becoming, for Warner Bros., a cheaper version of their biggest star, the “notoriously choosey” Bette Davis.

Then she decided to try something that fit no pattern that anyone, in the late 1940s, could recall—becoming a director herself. Lupino used marriage and what she called her “maternal wiles” to carve out a publicly acceptable image, so that she could make the subversive movies she wanted, inspired by the Italian neorealists—like the phenomenally successful low-budget drama Not Wanted, which told the stories of unmarried mothers. Longworth is astute on the pressure Lupino was under, in one of the most flagrantly misogynistic eras in modern American history, to establish herself as a professional without appearing to be so: She became known on her sets as “Mother” and portrayed herself in the press as a nurturing figure, whose primary commitment was still to her husband and family, rather than her creative work. “No director of the era,” Longworth writes, “worked as hard to diminish the public perception of their own power.”

Lupino was responding to a changed postwar Hollywood, which reflected a distaste for proudly independent women in the wider culture. Katharine Hepburn was one of the few women at that time who was able to, as Longworth puts it, “carve out spaces for her own freedom thanks to her alliances with powerful men.” Hepburn met Hughes in 1935 when he landed his airplane in the middle of the set of the movie she was filming. She thought the move was a cheap stunt, and was furious with her costar, Cary Grant, for inviting his buddy to show up unannounced.

It would be two years and two more serious romances on her part before Hepburn publicly partnered with Hughes, shortly before she was infamously blasted as “box office poison.” The gossip columns latched onto the story of “the damsel in distress rescued by a dashing aviator,” but they were more alike, and more equal, than that. Hepburn was, like Hughes, something of a daredevil and a germophobe; she was also wealthy in her own right, and carefully guarded her privacy. The romance worked for them both: It suggested that Hughes could be attracted to a sharp and smart woman, and it helped affirm Hepburn’s heterosexuality, which was frequently called into question, mostly due to her outspokenness, love of pants, and living with a female roommate.

In 1938, Hughes completed a record-breaking round-the-world flight, becoming “the most famous man in the world”—and newspapers everywhere speculated on whether he would propose. In fact, he had, more than once, but Hepburn turned him down. Shortly afterwards, she met Spencer Tracy, the love of the rest of her life. After his death, Hepburn burnished her relationship with Tracy as the ultimate Hollywood romance—but during his lifetime, and the nine films they made together, the relationship stayed secret, as Tracy was married. That meant that for a long time Hughes was Hepburn’s highest-profile romance. Again and again, Longworth’s book shows that power in Hollywood depends on who’s in charge of the story.

The roster of famous names with whom Hughes was paired throughout the 1930s and 1940s is seemingly endless, but it represents only a fraction of Hughes’s voracious appetite for women. Those high-profile actresses—silent star Billie Dove, Jean Harlow, Ava Gardner, Ginger Rogers, Ingrid Bergman, Jane Russell, and many others—managed to carve out a modicum of power for themselves in a ruthless business largely through their romantic relationships. A powerful man, a director or producer or costar, could become a husband or a lover, and serve as a protector. At the same time, as Jane Russell learned from director Howard Hawks on the set of Hughes’s The Outlaw, an actress “needed to learn how to set limits, and enforce them.” Male protection could only go so far. Sometimes, a woman had to defend herself—as Ava Gardner did after a beating from Hughes, by striking him in the face with a heavy bronze ornament. The MGM “fixers,” dispatched to clean up the messes of the studio’s valuable assets, made it clear to Gardner that it was she, not her violent boyfriend, who was in the wrong. But she had her limits, and the fight ended her affair with Hughes.

Ava Gardner with Hughes in 1946Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Ava Gardner with Hughes in 1946Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesHughes’s so-called “womanizing” was at once totally standard for his time, and deeply weird. There were people who said he was impotent, several who thought he was gay, and those who said—like Hepburn—that he was the best lover they ever had. But at some point in the early 1940s, Hughes’s tastes calcified. He no longer wanted stars, or even starlets: He wanted clones. Longworth identifies Russell as Hughes’s “physical ideal” from this point on: “Big breasts, brunette, high drama.” As he got older, his girlfriends stayed the same age. These teenagers rarely got the chance to make a movie, or to establish themselves independently. Hughes would choose them, lure them to Hollywood, sign them to personal contracts, and set them up in a hotel or an apartment where his extensive network of aides and spies would occupy their days and police their nights. It was a perverse kind of wooing that consisted mainly in keeping them waiting, and it’s shocking how many put up with it, as did their parents.

In a patriarchal cattle market, Hughes knew the power of a marriage proposal, and he threw them around like he threw money, proposing relentlessly to most of the women in his orbit, holding out a figurative diamond ring (or often a literal one) as part of a transaction of virginity. The girls had been raised to assume that a proposal was a kind of binding contract, but Hughes, whose entire life was a dance of contracts, knew it was not. He married twice, first to Ella Rice, a Texan heiress, when he was nineteen (whom he shed as soon as he moved to Hollywood to make movies), and late in life to actress Jean Peters, who lived with him only briefly and barely saw him, as he became more and more reclusive.

But he also convinced devout Mormon Terry Moore that a ceremony conducted on a yacht and recorded in a ship’s log was legally binding, mostly so she would sleep with him—and after his death, Moore would devote years to insisting that she had actually married Hughes and was owed a cut of his estate. Hughes spent his life defying the forces—matrimony, taxes, family, gravity—that governed the lives of most ordinary people. Clearly he got off on controlling women, but what that means isn’t quite clear. If a beautiful wife is a trophy, or a “billboard” (as Longworth puts it in her account of the Ava Gardner movie The Barefoot Contessa, which she sees as presenting a version of the actress’s relationship with Hughes), it remains mysterious what victory Hughes wanted to celebrate, or what message he was trying to send.

It makes sense that when Hughes retreated from the world, he went into the movies: renting out screening rooms around town for months at a time, hiring a projectionist to run, over and over again, his favorite movies, with his favorite girls. Even though he owned his own studio, RKO, he spent months in a room on the Samuel Goldwyn lot, until he learned that it had been used by the predominantly black cast of Otto Preminger’s Porgy and Bess, and abandoned it. His racism, Longworth argues, was tied up with his germophobia; it was a visceral, irrational fear that went far beyond the common prejudices of the time.

Because most people in town respected the sanctity of a movie theater while the film was running, he could hide out from all the people he didn’t want to see: his wife, his other women, his staff, his shareholders. He ate barely anything, swallowed and later injected codeine and Valium, and sat naked in front of a movie screen, taking the hypnotic magic of cinema to its most screwed-up extreme. Something similar happens when we lose ourselves in the story of Howard Hughes—the outside world recedes to a muffled distance. Wars happen and enrich the millionaire further through his manufacturing contracts with the government. American society takes a sharp, stifling turn toward domesticity and conformity in the 1950s and that also benefits him, by confirming his vision of women as the domesticated playthings of powerful men.

There is no doubt some schadenfreude lurking in the fascination with Hughes, as there is in any story about a powerful man’s slow slide out of public life into a private hell of his own making. The legend that lingers in American culture, and the version portrayed by DiCaprio, is of “eccentricity” grown unmanageable, as Hughes barricaded himself first in studio screening rooms, then hotel suites, for weeks and months at a time. His hair and fingernails grew long and filthy, he touched nothing without a protective Kleenex, and grew dependent on painkillers. Throughout the 1960s until his death in 1976, he moved between the Bahamas, Nicaragua, Las Vegas, and other American cities, between hotels that he would sometimes buy to ensure his privacy. An entourage of staff insulated him from the world. The man retreated into myth.

It is tempting to shuffle possible, posthumous diagnoses of Hughes, whether they’re cultural or medical: head trauma from one too many plane crashes; undiagnosed epilepsy (perhaps the cause of all those crashes); secret syphilis; that hypochondriac mother. But as Longworth makes clear, a focus on “what went wrong” in his later years requires that we see the younger Hughes as basically decent and healthy—and it’s only possible to do that if we think it’s really no big deal to scout young women as though the entire world is a catalog, and then, essentially, to purchase and imprison them. In other words, if we celebrate megalomania and gilded male privilege run amok as quintessential American values.

Hollywood’s post-Weinstein reckoning with the entertainment industry’s treatment of women suggests that those values can be questioned. Longworth’s essential book reclaims the narrative from a man who obsessively sought to control it and from the many other men who benefited. She reminds us that abuses of power might be common, but they should not be routine. Instead, they need to be called out and protested, over and over again. Listening to women is a start.

In late November, a group of migrant women from Central America stood outside the Enclave Caracol community center in Tijuana, and announced the beginning of a hunger strike. They would not eat, they said in Spanish, until the United States and Mexico expedited the process for letting asylum seekers across the border.

Earlier that month, the Trump administration had tried to change not only who was eligible for asylum but also where they could apply. As part of his ongoing effort to restrict immigration from poorer countries, he announced that anyone who had crossed the border without authorization would be automatically disqualified from asylum proceedings. (Previously, anyone could apply, as long as they showed a “credible fear” of returning home.) Immigrants would now have to present themselves at an official port of entry, like San Ysidro, just across from Tijuana, or Hidalgo, near McAllen, Texas, and wait—a process that could keep them on the Mexican side of the border for several months.

When I visited Tijuana in late November, a judge had already halted Trump’s newest asylum restriction. But the city still housed an estimated 7,000 migrants, most of whom had traveled north in the Central American caravans that Trump had worked to cast as dangerous invaders. U.S. Customs and Border Protection was only taking in between 40 and 100 asylum seekers each day, leaving thousands waiting in the one main makeshift government shelter on the Mexican side of the border, where they slept outside, many without tents. To bring some semblance of order to what has become a complicated and opaque process, a small group of migrants began keeping a list to ensure that those wishing to enter the United States to request asylum did so in the order they had arrived at the border. La lista, as it is known, exists as a handwritten ledger and is passed to new caretakers as the older ones depart. It is a bizarre by-product of the Trump administration’s policies, effectively outsourcing American immigration enforcement to Mexico, and sometimes even to the migrants themselves.

This kind of outsourcing isn’t entirely new. After NAFTA was implemented in 1994, many once-sleepy border crossings became militarized checkpoints where American authorities collaborated with Mexico to fight smuggling and drug trafficking and later, after September 11, terrorism. In 2014, the Obama administration gave Mexico’s government funds to increase its immigration enforcement and deportation efforts in Chiapas, its southernmost state. (As a result, the number of people apprehended in the United States dropped 30 percent within a year.)

But the burden President Donald Trump is foisting onto Mexico today is unprecedented. In November, The Washington Post reported that Mexico’s newly elected president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, had struck a deal with the Trump administration to make the Mexican side of the border a permanent way station for asylum seekers bound for the United States. Once the story was published, López Obrador’s administration denied it. But even so, thousands of migrants remain on the Mexican side, waiting to hear who will decide their fate. Never before has Mexico had to house so many people indefinitely. Trump, said Arturo Sarukhan, a former Mexican ambassador to the United States, is continuing to use Mexico “as an electoral and political piñata.” The country has become “a de facto filter to the U.S.” without getting anything in return.

In 2015, more than a million migrants made their way to Europe, and the backlash to their sudden arrival destabilized the politics of the entire continent. Though migrants have been arriving in Mexico for a long time, their presence has created many of the same problems. The government in Tijuana hasn’t embraced the encampment, nor have many residents. In November, hundreds of Mexicans marched to protest the camp’s existence, some of them shouting “Tijuana first!” and “no more migrants!” while the mayor, who has called on the caravan leaders to be prosecuted for bringing the migrants into the country, appeared wearing a red “Make Tijuana great again” baseball hat.

Conditions inside the shelters and encampments are dire. When I visited the main camp, an open-air soccer stadium packed with tents and makeshift shelters, it was raining. By midday, after hours of heavy downpour, the stadium floor had turned to mud. People packed into the Enclave Caracol, where a volunteer organization called Food Not Bombs dished up warm meals. (A few months earlier, they’d been serving 150 meals a day in Tijuana, mostly to Mexicans who’d been deported from the United States; now it’s 500, almost entirely for migrants who are heading into the United States.) Despite the weather, the months spent on the road, and the prospect of deportation, the mood was cheery: A DJ was playing pop music on the speakers; small children ran around the feet of adults who chatted over steaming heaps of pasta and cups of coffee.

The government has struggled to feed, house, and clothe the refugees. Every day, thousands of people need to eat; they need medical care, jackets, and blankets; children need diapers, and women sanitary pads. Given the limited resources and organizational capacity of Mexican authorities, groups like Food Not Bombs have stepped in, as have legal service providers and other humanitarian organizations. I spoke to a woman named Elodia, who had fled Guatemala with her two children, leaving behind an abusive husband who had burned down her family’s house after she’d tried to leave him. A volunteer had just handed her a packet of four diapers. At least it would get her through the next couple of days, she said. What she really needed, though, was a chance to plead her case for safety in the United States.

The human consequences of trapping migrants along the border are self-evident. The political ones may also be severe—for Mexico and for the United States. When Germany forced countries on Europe’s periphery to bear the responsibility for housing the majority of migrants, it did little to quell—and may even have exacerbated—xenophobic uprisings in that nation and throughout the European Union.

Later the night I was there, the standing water at the Benito Juárez stadium was ankle-deep. People had lost many of their things: the clothing, bedding, mats that they needed to stay warm and dry and alive. The government announced that it was closing the shelter and opening another one about 30 minutes away, in a former concert hall—a place with few amenities, but, at least, a roof. Hundreds packed their belongings and loaded onto government buses.

Others decided to stay. “Why would I trust the government?” a Salvadoran man told me. There were rumors that the new shelter was an old jail, that the move was a trap to lock migrants up and then ship them back home. From inside the Benito Juárez stadium, you could see the border itself, and the wall that cut like a spine across the sky.

By morning, the water had receded; all that was left was the detritus of what had been lost and ruined. Meanwhile, the hunger strikers continued to refuse food, hoping that someone would take notice and meet their relatively humble demands: to cross the border into the United States, be put into detention, and plead for the right to protection under the U.S. law.

Disney’s Mary Poppins Returns, the feverishly anticipated sequel to the 1964 original, is incandescent. In the opening scene, the camera looms above the flame of a street lamp, just before Jack (Lin-Manuel Miranda), a lamplighter and the film’s narrator, extinguishes it. Daylight is breaking in pinky yellow, and Jack careens through the city on his bicycle, directing our attention toward “the lovely London sky.” Later, the Banks family, each of them grasping a plump balloon, wafts and bobs about a dazzling blue sky, buoyant with whimsy. With diligent tenderness, the film pursues lightness—how to cultivate it, how to be it. No longer are we merely concerned with one self-satisfied father’s aloofness toward his children—a conflict treated in the first film as no less than a battle for his soul—but instead we must contend with a far knottier conundrum: how to be happy in the wake of tragedy.

These are timely lessons, as we quickly learn. Set in 1930s London, England heaves under the strain of the Great Depression, and the Banks family is in the throes of financial and emotional crisis. Jane and Michael, the children of George and Winifred Banks (David Tomlinson and Glynis Johns)—and Mary Poppins’s charges in the first film—are now fully grown. Michael (Ben Whishaw), an artist and part-time bank teller, lives with his own family in the Banks homestead on Cherry Tree Lane. But a funereal gloom has descended on them: Michael grieves the death of his wife Kate and staggers in the melancholic, yet frenetic aftermath. Bewildered by the prospect of managing a household—previously his wife’s domain—he relies upon his sister Jane (Emily Mortimer), as well as his three small children, Anabel (Pixie Davis), John (Nathanael Saleh), and Georgie (Joel Dawson).

The family’s circumstances are precarious at best. The children, courageous and capable, strive to assuage their father’s burden, and Jane, now a labor organizer, tends to them with the empathy that her mother largely lacked. The tipping point arrives early in the film when a disheveled Michael learns that because he has not repaid a loan to the bank, and because he has lost the certificate verifying the shares his father purchased for him, he will lose the family home—if, that is, he cannot scrounge up the certificate, or the cash, in a perilously short space of time.

These are high stakes. Here is a bereaved family so topsy-turvy that mourning becomes an afterthought, and the children must thrive on responsibility instead of wonder. And in the midst of all this, they are threatened with homelessness. Of course we know that the Banks family will never come to ruin—not when Mary Poppins can wield her influence—but the gravity of their predicament, and their yen for solace in the murk of pain and insecurity, imbue the film with resonant somberness.

When Mary Poppins (Emily Blunt) arrives, she glides through the Banks’s door with characteristic primness and ease, reminding an astonished Michael that “we are still not a codfish.” Blunt’s interpretation of the character draws elegantly on Julie Andrews’s presentation of pleasant self-assurance while introducing a dash of beguiling humor. Blunt’s Poppins nods jovially at the family’s disbelief, while anticipating the pleasure of enveloping them in a second whirlwind of magic. She conjures wonder in order to nourish her charges with both joy and confidence in their burgeoning imaginations. And while Mary Poppins Returns thankfully draws less gawking attention to the titular character’s physical charms, Mary is, of course, immaculately coiffed, with an enviably snappy collection of coats and kitten heels, and she is just a bit vain. When Jane and Michael exclaim that it is marvelous to see her again, she agrees while primping in the entryway mirror.

In superficial terms, Mary resumes her post to do what she did years before: to care for the Banks children. But just as before, her aims are finespun and rather more challenging. She must demonstrate to the Banks children the nurturing potential of pleasure and fancy—“some stuff and nonsense could be fun,” she sings—while gently encouraging them to mourn their mother. I happened to attend a press screening on the day preceding the one year anniversary of my own mother’s death; perhaps unsurprisingly, I melted into tears as Blunt delivered a compassionate and graceful performance of “The Place Where the Lost Things Go,” wherein she reassures Anabel, John, and Georgie that death never means annihilation, but rather a cosmic rearrangement. The song supplies an answer to Michael’s earlier lament, “A Conversation,” in which he considers how his late wife always knew what to do, and how in her absence he is bereft. “Where’d you go?” he wonders, slouched in the attic, encompassed by dust-soft relics from his childhood and marriage.

Although Mary Poppins Returns is an ardent, nearly shot-for-shot love letter to the first film, its more somber thematic premise pairs with its efforts to craft characters and a narrative that are more culturally evolved. In order to incorporate Jack into the larger Poppins narrative, the film introduces him as a former chimney sweep who, as a child, was under Bert’s tutelage and who, conveniently, did not die of black lung before adolescence. He and Mary revel in one another’s company with platonic warmth; there are no traces of the sexual disappointment Bert (Dick Van Dyke) betrays during “Jolly Holiday” when Mary thanks him for “never pressing [his] advantage” and summarily indicates that they will never be an item. In fact, we learn that Jack has adored Jane Banks since youth, formerly gazing up at her nursery window, an image making manifest the socioeconomic berth that once precluded their companionship.

Ben Whishaw’s paternal masculinity is at once cottony and slightly tremulous: an empathetic portrayal of someone determined to be the sort of father that his own probably wasn’t.As an adult, neither Jane nor her family harbor any sense of class superiority, and she and Jack timidly—and very adorably—enter into a fledgling romance. Admiral Boom (David Warner) still presides over Cherry Tree Lane with militant neurosis, and he still possesses a baffling cache of gunpowder and weaponry, but he is mercifully no longer sputtering racial epithets. Michael, despite some spare, intermittent endeavors to project a stiff upper lip, allows his children to bear witness to his sorrow and, in pointed contrast with his father, never leaves them in question of his love. Ben Whishaw’s paternal masculinity is at once cottony and slightly tremulous: an empathetic portrayal of someone determined to be the sort of father that his own probably wasn’t.

Yet, until his wife’s death, he was, in all likelihood, a relatively passive parent—not as a result of patriarchal disconnect or apathy, but because he is, over the course of the film, still cultivating the assertiveness Kate seems to have possessed, and that he needs in order to advocate for his family. When the score drifts into his father’s theme, “The Life I Lead,” it settles against Michael’s troubled countenance like a sonic subconscious, as he muddles over what sort of father to be; that is to say, what sort of father will deliver his family from their financial catastrophe and regain the pacific household atmosphere fostered by his wife. Unlike so many men of his era, he must accustom himself to domesticity.

By contrast, the film indicates that Jane Banks, who lives alone in a London flat, sports trousers, and organizes labor union rallies, will not exchange autonomy for romantic companionship, and Jack, who appreciates her progressive politics, seems like the sort of partner who will both understand and embrace these terms. Mortimer, a preposterously under-celebrated actress, crafts Jane’s character with luminous precision: She is beaming and passionate, a steady, smiling port in the storm for her brother, niece, and nephews. It is Jane who eagerly urges Mary Poppins to resume her post while Michael frets about wages (it’s unclear whether Mary actually cares about being paid for her labor, or if she needs the money; she tends to broach the discussion as a matter of ceremony and then just as quickly wave it away).

The question of financial stability looms throughout the rest of the film, and is rather unfortunately entwined in its narrative resolution. The emotional climax seems to arrive as the Banks family bids farewell to their home, resigned to the loss of the bank share certificate but flush with familial solidarity, regardless of place or material goods. But they are rescued at the eleventh hour by Michael’s tuppence—the ones he intended for feeding the birds twenty years ago. At the conclusion of the 1964 film, George Banks, having just been fired in a most humiliating fashion, thrusts his son’s coins into the hand of his boss, Mr. Dawes Senior: “Guard it well,” Banks sneers, in parting. Dawes Senior kicks the bucket hours later, but his son, Mr. Dawes Junior (a jubilant cameo from Dick Van Dyke in the 2018 film) seems to have taken George Banks’s words to heart. In a somewhat muddled turn of events, he explains to Michael that he invested the money for his future use; it is enough to settle his debt and to restore the family to middle-class comfort.

Adult Michael is, understandably, thrilled by this monetary deus ex machina: his family, after all, can keep their home. But in the first film, young Michael appeared appropriately horrified by the imperialist endeavors of his father’s employers—the “railways through Africa” and “plantations of ripening tea” recited in “Fidelity Fiduciary Bank.” We can assume little Michael doesn’t comprehend the racist colonial politics of the executives, and perhaps the 1964 film wasn’t too concerned with them either. And yet, when George, backed by the chorus of bank partners, pressures young Michael to choose responsibility over whimsy, and his son refuses, the scene registers as a defiant condemnation of corporate greed.

The end of the film also reduces Mary Poppins’s role to something less magical than it could be. Her involvement in defeating the wicked banker William Weatherall Wilkins (Colin Firth), at the film’s climax, pushes her intangible, and altogether more pivotal, support to the margins. Instead of encouraging the children’s imaginations—unlocked and jubilantly voracious—it reduces the story to a problem with money, solved in the nick of time.

These, however, are comparatively minor quibbles regarding a film that is not only exquisitely artful, but also a tenderly applied balm. “Everything is possible, even the impossible,” declares Mary, delivering, as usual, an exuberant paradox. In these last years, we have inhabited terrifying paradoxes, navigating a reality the most privileged of us had always deemed impossible, a Poppinsian world turned inside out and viciously deformed. And yet, Mary Poppins Returns encourages us to hope anyway, to conjure luminescence however we can, to commit the blazing, radical act of believing whatever seems most impossible now.

We chew over the latest news, rumors, and release date information for Intel's new discrete gaming graphics cards.

We chew over the latest news, rumors, and release date information for Intel's new discrete gaming graphics cards.

No comments :

Post a Comment