In May 2017, Erin Kearns, an adjunct instructor at American University, gave a lecture on terrorism in the United States. Jihadists, she said, commit only a small portion of attacks on American soil, just 12 percent—far fewer, in fact, than right-wing extremists do. People with far-right beliefs, like white supremacists and nationalists, were responsible for 35 percent of the attacks that had happened on American soil over the previous seven years, up from 6 percent in the 2000s. Not long after Kearns’s lecture, conservative media sites the Daily Caller and College Fix ran articles attacking her and her methodology. PJ Media said she had been “trying to indoctrinate college students.” (Jihadists, they pointed out, had killed a greater number of people.)

The data Kearns used was solid, however. It had been gathered by the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database, which was founded in 2002, shortly after the September 11 attacks. Since 2005, officials at the departments of State and Homeland Security have used the GTD’s roughly 180,000 entries, each one listing a terrorist incident around the world, to analyze patterns of violence and develop counterterrorism strategies. The entries date as far back as 1970. Homeland Security provided much of the funding for the project in its early years, and since 2012, State has taken it on.

The summer after Kearns’s lecture at American, Erin Miller, a criminologist who runs the GTD, learned that the federal government would no longer be funding the organization’s work. The State Department had decided to give the contract to a firm based in Bethesda, Maryland, Development Services Group Inc., which had partnered with a terrorism center at George Mason University.

In August, the University of Maryland filed an official protest with the Government Accountability Office, alleging, among other things, that the State Department was biased against it. The Trump administration, for its part, claimed it made its decision on the basis of cost (Development Services had advanced a slightly lower bid for the contract), and the GAO dismissed the charge. But the Global Terrorism Database is not the first program to be shuttered after it called attention to the rise in violence on the right. Shortly after Donald Trump took office, the administration rescinded a $400,000 grant to Life After Hate, a group dedicated to stopping right-wing extremism in America. The Department of Homeland Security also backed out of a $867,000 grant promised to researchers at the University of North Carolina who were developing a program to stop young people from embracing ideologies like jihadism and white supremacy. The Office of Community Partnership, an arm of DHS whose mission is to prevent violent extremism before it begins, had administered those grants. After Trump took office, its name was changed, its staff cut in half, and its budget slashed by more than 85 percent.

Republicans have tried to bury reports about right-wing terror before. Perhaps the best-known instance occurred in 2009, when the Department of Homeland Security, under Obama appointee Janet Napolitano, released an intelligence brief outlining how white supremacists, radical anti-abortionists, and a few “disgruntled” veterans were particularly susceptible to radicalization. When the document leaked to conservative media outlets, Republicans on Capitol Hill were furious; Minority Leader John Boehner called it “simply outrageous” that Napolitano would seek to demonize conservatives, and Napolitano eventually apologized. (A month later, a pro-life extremist shot George Tiller, a doctor in Wichita, Kansas, who worked at a local abortion clinic. Ten days after that, a neo-Nazi killed a security guard at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.)

The situation with the GTD, however, is different, and arguably more troubling, because, as president, Trump has often pushed ideas about terrorist violence that directly contravene the available data. He has not only firmly maintained that the “alt-left” is as dangerous as the “alt-right” (“I think there is blame on both sides,” he said after the protests in Charlottesville—something not borne out in the data, which shows that right-wing extremists have become much more active than left-wing extremists in the last ten years), but also that immigrants are inciting violence in the United States. On the campaign trail, he’d refer to Somalian refugees “joining ISIS and spreading their extremist views all over our country and all over the world.” Here again, the data indisputably contradicts him; most convicted domestic terrorists are U.S. citizens.

Miller does not believe her team lost funding because of what their data showed. But she still has more questions than answers about the bid. In the meantime, she’s seeking new sources of funding to keep the database going, and is hopeful something will emerge. If it doesn’t, a key resource for academics, journalists, and governments will likely be lost. The data collected by the new contractor will almost certainly not be compatible with that accumulated by the GTD, Miller said. The two data sets will have different quantifiers and coding, and with completely different data collection methodologies, it will be difficult for researchers to track trends accurately across two platforms. In the past, such data helped provide lawmakers with what Miller called “an empirically grounded understanding of a topic that is at times very politicized and very emotional.” Whether that understanding will still be based on the facts under the Trump administration is unclear.

House Democrats had big plans for opening the 116th Congress, with showy votes on cracking down on government corruption and protecting pre-existing conditions. But such plans rarely survive contact with reality. The party’s takeover of the House on Thursday coincides with Day 13 of a partial government shutdown of nine cabinet-level departments, a crisis that takes precedence over every other legislative priority.

Nancy Pelosi, the presumptive House speaker, has outlined a two-bill package to fund the government, which will get a vote on Thursday. It’s not likely to end the impasse, but it does signal an intention to make good on promises to the 800,000 or so federal workers who haven’t received a paycheck since the shutdown. Section 2 of the second bill states that “employees furloughed as a result of the lapse in appropriations … shall be compensated at their standard rate of compensation” for the time that they’ve missed.

But only federal employees would be covered by this back-pay clause. That excludes everyone who toils for a federal contractor, particularly the low-wage workers who clean, secure, and staff federal buildings—around 2,000 of them, according to the Service Employees International Union. When the Smithsonian museums and the National Zoo closed on Wednesday, contract workers who provide concessions and take tickets also got sent home, adding to the ranks.

Contractors are the most vulnerable people in the federal workforce, the ones who can least afford a disruption in their pay. And yet, in the aftermath of government shutdowns, they are the only employees who don’t get compensated after the fact. In 2013, when the government closed for 16 days, federal workers received back pay, but low-wage contractors did not, causing serious financial depression for struggling families in Washington. “When the politicians closed the government, they didn’t think about the impact it would have on our families,” Pablo Lazaro, a cook at a Smithsonian museum, said at the time.

Workers in those same jobs half a decade later fear the future, as President Trump and Congress wrangle over a border wall. “I wouldn’t buy any Christmas gifts knowing the government is gonna shut down,” Bonita Williams, a janitor at the State Department, told the Washington Post. Others worried about being unable to pay their rent or car insurance or utilities. And this will only get worse as the shutdown continues.

The federal government is effectively the nation’s largest employer of low-wage workers: It funds 4.5 million contractor jobs that pay less than $15 an hour, according to Good Jobs Nation. Thanks to an executive order from President Obama in 2014, the minimum wage for federal contract employees was boosted to $10.35. But that’s not enough to keep these workers out of poverty, even when they’re not missing paychecks due to a shutdown.

Eleanor Holmes Norton, who represents many of these workers as the House delegate from the District of Columbia, has been their lonely champion over the years. Of course, Holmes Norton doesn’t get a vote that counts in Congress.

It’s immoral for Congress to protect every federal worker except those who are earning the lowest wages in the government. Their struggle ought to be the first priority for the new crop of freshman progressives—like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, and Rashida Tlaib—who are entering Congress with bold pledges to fight for the poor and downtrodden. For Pelosi’s government-funding package to pass the House on a party-line vote, she can’t afford more than 17 nays from Democrats. So even a small fraction of Progressive Caucus members could force her to include a provision providing back pay to federal contractors.

It would not cost an exorbitant sum to do right by these workers. Reimbursing 2,000 contract janitors and security guards for three weeks’ pay at the D.C. minimum wage of $13.25 an hour comes out to $3.18 million—not even a rounding error in the total U.S. budget.

Contract workers are habitually the ultimate victims of power plays between the White House and Congress. That has to end. There’s no good argument for protecting federal workers, as is done routinely, while janitors and security guards get quietly stiffed. This is now a test for left-wing Democrats. You can give speeches about being an advocate for low-wage workers, but that’s worthless if you’re not speaking up for them when they need it the most.

The story has never failed to entrance a foreign audience: An outspoken leftist committed to social justice wins a landslide presidential victory in Latin America. Headlines last July for 65-year-old Andrés Manuel López Obrador proclaimed the familiar tale. Mexico’s poor, marginalized, and forgotten had elected a man who would truly represent them: a plain-talking, frugally living southerner who would stamp out corruption and give voice to the voiceless.

Yet with his promises to increase state economic intervention and potentially reverse Mexico’s market reforms of the past 30 years, AMLO, as he is known, polarizes opinion. Supporters, both at home and abroad, believe he and his National Regeneration Movement party (Morena) are the antidote to the neoliberal policies that have left the country mired in gang violence and inequality. Critics, meanwhile, compare him to Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez—a potential authoritarian who will wreck the economy.

Mexico’s challenges since transitioning from one-party-rule to democracy in the 1990s are so numerous and complex—corruption, drug violence, the rule of law—that the most probable outcome is that AMLO, like his predecessors, merely disappoints. Yet there’s ample reason to suspect those dubbing him the “Mexican Bernie Sanders” are misreading the situation: projecting southwards an American leftist fantasy that fails to engage with Mexican reality. The man who has vowed to initiate Mexico’s “Fourth Transformation” is not free of flaws. And some of them come uncomfortably close to those which have long led the left astray in Latin America.

It is debatable whether AMLO, who was sworn in December 1, won July’s election because of a longing by Mexicans to see the left return to power, or simply because of widespread disenchantment with their entire political class. Former president Enrique Peña Nieto’s six-year term was beset by corruption scandals, drug violence, and a batch of pro-market structural reforms that have yet to benefit the majority of the population. Exhibiting equal parts arrogance and incompetence, the centrist Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) politician symbolized the very worst of Mexico’s ruling class. The 2018 election could credibly be read as the country’s “Trump moment,” a desire for something—anything—different.

Mexico, for all the catastrophizing by politicians, the media, and NGO researchers, remains a country in flux rather than crisis. Its violent crime rate, while the source of horrific massacres and mass disappearances, is lower than those of Venezuela, Brazil, or Colombia. Its burgeoning high-tech and manufacturing sectors are the most productive and innovative in Latin America. And its current economic performance—relatively low, if consistent, growth—while disappointing to many, can be considered an improvement on the 20th century when Mexico lurched from crisis to crisis, depending on oil prices.

Ultimately, where Mexico continues to struggle is in the consolidation of democratic institutions and the rule of law—the legacy of decades of authoritarianism. Weak public institutions undermine everything from criminal justice to the implementation of social welfare policy and prevent any government, right or left, from meeting its goals. They permit corruption to continue, and serve as background to the catastrophic images of death and mayhem that flit across our screens after the latest drug war massacre.

Many in western academia and journalism continue to consider neoliberalism the region’s primary problem.Yet this is generally not the discussion being had on the left with regards to Latin America. Many in western academia and journalism continue to consider neoliberalism the region’s primary problem. This posture was first adopted by the left in the 1990s during the alter-globalization movement, itself partly inspired by Mexico’s 1994 “Zapatista” uprising, and has endured as the foremost leftist critique of Latin American governments to this day. While many of the criticisms of the rapid implementation of liberalizing market policies were justified, they rarely appreciated the context of the times or distinguished between positive reforms and negative ones.

Mexico’s market reforms, after all, were spurred by serious problems. While the Mexican economy, propelled by oil revenues, grew rapidly during the mid-20th century, state-backed monopolies filled with political cronies only served to suppress innovation and entrepreneurship, while state intervention in the economy through land reform and price controls simply maintained one-party hegemony, culminating in the disastrous Latin American Debt Crisis of 1982. Notably, Mexico today is growing more robustly in its north, which has been quicker to embrace industrialization and global trade, than its rural and politically volatile south, which only seems to fall further back.

AMLO’s policy proposals are not so much radical or innovative as retro. Steeped in nationalist symbolism, his economic plans in particular echo the country’s leftist leaders of the 1970s, whose profligate spending contributed to the 1982 debt crisis. Specifically, he has suggested considerable public reinvestment in Mexico’s corrupt, unwieldy energy giant, Pemex, implicated in the region-wide Odebrecht scandal; a revival of the agricultural sector, which was in steep decline even before the market reforms; and increased public spending. After decades of financing development via oil revenues and foreign loans, such increased spending cannot now occur sustainably without tax reform—something AMLO so far has resisted.

Few members of the recent “Pink Tide” of leftist leaders in Latin America have attempted to tackle the pervasive issue of tax reform, preferring to gamble on the short-termism of commodity booms. The reasons for this impasse are various: in many countries, millions work in the untaxed informal economy; the middle class resents paying taxes to governments they—correctly—perceive as corrupt and rapacious; tax evasion among the rich is rampant. But failing to broaden the tax base has also had consequences. Even moderate governments in Brazil and Argentina have driven their countries into minor crises through reckless spending in recent years, ultimately wiping out the economic gains for the poor upon which they had defended their records and opening the door for dangerous right-wing populists like Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro.

In these and other respects, AMLO more closely resembles the ambiguous Latin American leftists of yesteryear than Bernie Sanders or British Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, to whom his supporters often compare him, and the latter with whom he has a personal friendship. In addition to a certain realism regarding public finances, Sanders and Corbyn recognize the fundamental role of the rule of law in their countries, understand the importance of checks and balances, and are more than willing to expel corrupt figures from their own ranks. Conversely, AMLO has dismissed growing demands for an independent attorney general and anti-corruption prosecutor, stating openly that the president alone should dictate who among the corrupt falls and flourishes. He has twice, in 2006 and 2012, claimed fraud upon losing an election, without sufficient evidence. He has dubbed journalistic critics members of the prensa fifí—or “fancy press”—a troubling stance in a country where journalists are murdered with impunity. Already boasting majorities in both houses of Mexico’s congress, he has repeatedly touted the possibility of dismantling some of the country’s few genuinely independent institutions, such as the National Electoral Institute, the National Transparency Institute, and the National Human Rights Commission, all of which have been important, if flawed, building blocks in Mexico’s transition to democracy.

The international community still lacks a healthy debate regarding the failings of the Latin American left. During his campaign, AMLO’s harshest critics frequently called him a “danger” to the country, prompting a number of moderates, as well as leftists, to defend him against what they perceived as right-wing attacks. The resulting political climate, evident on social media, is not dissimilar to that of the U.S. post-Trump, in which battle lines have been drawn and the desire for outright attack stifles nuanced debate. This, naturally, is a gift to any politician, left or right, looking to trample on democracy and amass power.

The key point made by AMLO’s critics, many of whom would identify themselves as moderate, or even progressive, is lost: For decades, Mexico’s great mistake has been to believe that there are shortcuts to sustainable development. In reality, prioritizing cheerleading for a candidate over the slow but vital work of institution building, sustainable budgeting, and rigorous anti-corruption enforcement has led to patchy results. Enthusiasm for a new leftist hero shouldn’t obscure either the particulars of Mexico’s needs or its new president’s very obvious shortcomings.

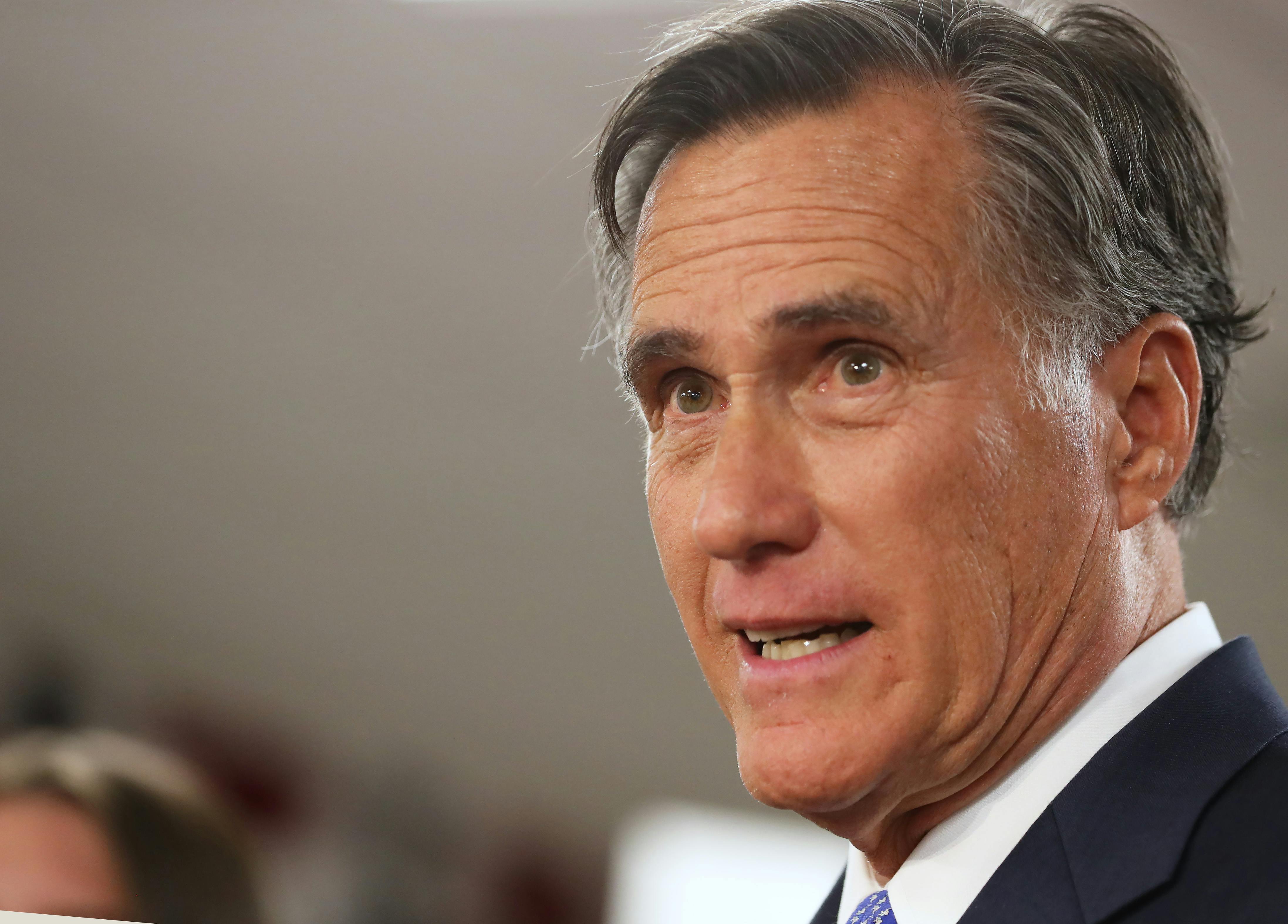

Mitt Romney isn’t a big fan of this Donald Trump character, and he really wants you to know it. The former Republican presidential candidate and Utah’s newest senator wrote a Washington Post op-ed on Wednesday in which he said the president has not “risen to the mantle of the office.” This is an understatement, to say the least. Trump is crass and belligerent, thoughtless and undisciplined, racist and sexist. Reaching this conclusion is like announcing that January is the first month of the year.

Such critiques nonetheless comprise a well-trod genre for a small minority of Republican lawmakers. The authors are typically elder statesmen who could withstand any electoral blowback, like the late John McCain, or retiring senators like Bob Corker who no longer needed to worry about it. Jeff Flake, Arizona’s departing senator, carved out a national reputation over the last two years by begging the president to be a nicer person, all while doing little to obstruct his policy agenda in any meaningful way.

Romney’s latest writing is a declaration of sorts that he, too, will join the ranks of the Op-Ed Republicans when he takes his seat later this week. Trump himself noted the similarities on Wednesday morning, asking on Twitter if the new senator would turn out to be “a Flake.”

Here we go with Mitt Romney, but so fast! Question will be, is he a Flake? I hope not. Would much prefer that Mitt focus on Border Security and so many other things where he can be helpful. I won big, and he didn’t. He should be happy for all Republicans. Be a TEAM player & WIN!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 2, 2019This is a relatively mild rebuke by Trump’s standards, which suggests he sees Romney as minor a threat as Flake was. “He agrees with many of the things we’ve done, and many of the things we have in mind, and we’ll see what happens,” Trump told reporters on Wednesday afternoon.

That’s a fair reading of Romney’s op-ed. “It is not that all of the president’s policies have been misguided,” he wrote. “He was right to align U.S. corporate taxes with those of global competitors, to strip out excessive regulations, to crack down on China’s unfair trade practices, to reform criminal justice and to appoint conservative judges. These are policies mainstream Republicans have promoted for years. But policies and appointments are only a part of a presidency.”

What’s most striking about the op-ed is what it doesn’t mention. There are no complaints about Trump’s draconian approach to immigration, perhaps because Romney himself helped pave the way for his hardline policies. During the 2012 primaries, he outflanked the rest of the field from the right by calling for policies that would pressure immigrants to “self-deport” as an alternative to mass deportations. The years have not tempered his views: “I’m also more of a hawk on immigration than even the president,” Romney told a Utah crowd in March.

Romney’s op-ed reveals a selective memory at play. His version of events begins with his own decision not to endorse Trump in 2016. But during the 2012 campaign,

Romney appeared alongside Trump to accept his endorsement, a decision that helped pave the way for Trump’s subsequent rise to power: It validated his racist campaign to pressure President Obama into releasing his birth certificate, and signaled that he had power and influence within the Republican Party. Romney’s pointed non-endorsement in 2016 was too late to wash away the imprimatur of legitimacy.

The narrative also, conveniently for Romney, focuses on what happened in the last month of 2018. “The Trump presidency made a deep descent in December,” his op-ed began, as he lamented the departures of Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, and other figures whom establishment Republicans saw as stabilizing figures within the administration. Criticizing Trump’s actions prior to the midterm elections would have been slightly awkward for Romney: He welcomed the president’s endorsement in his own Senate campaign.

Some observers rushed to praise Romney for his perceived declaration of independence. “For better or worse, Mitt Romney has joined the resistance,” The Week’s Joel Mathis wrote on Wednesday. Rick Wilson, a prominent #NeverTrump conservative consultant, was euphoric. “Yes, we’ve seen a handful of truth-tellers in the Senate,” he wrote in The Daily Beast, “but they rarely hit so keenly as today’s Romney nuke strike.” If complaining that Trump has not “risen to the mantle of his office” is a nuclear detonation, even the most conservative of Democrats should be sent to the Hague.

Whenever Trump leaves office, there will be a debate about whether Trumpism can exist without him. Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions showed that it could be enforced as a policy platform, but there’s not much evidence it can survive as an electoral strategy beyond its namesake. This may be what irks the Op-Ed Republicans the most, and why they complain about Trump’s style instead of his substance: They largely agree on the latter, but realize the former is the key to his political success. There’s not a huge constituency for a polite Trump. If there were, Romney would be halfway through his second term.

By the time thunderstorms hit the eastern Montana prairie just after seven on the morning of August 2, 2017, Audemio Orózco Ramirez had been up and driving south for a couple of hours. He was making the four-hour trip to Billings from Vida, the tiny hamlet where he’d been working as a ranch hand for nearly four years. Audemio, then 44, and his wife, Amparo, 37, lived on a ranch in a one-story house with a wide front porch. With eight children still at home, it was tight quarters, but they had endured much worse in the two decades since they had crossed the border together near San Diego with their infant son, Juan Luís. Before this most recent gig, they’d lived in a tumbledown trailer in Sidney, Montana, within sight of a feedlot, barely better than the shacks the migrant workers slept in when they used to come up from Mexico to weed the sugar beet fields. They did not have so much as a leaf for shade, and the sun turned that trailer into an oven. The water, which they didn’t dare drink, ran brown from the spigot.

In Vida, the children had a whole ranch to roam, just as Audemio did when he was a kid in Michoacán. Back then, Audemio and his brothers scaled the mountains that shot up from the forest canopy. They hunted javelinas and quail and ate fresh mangoes straight from the trees. It made Audemio proud to re-create a piece of his childhood for his children. He taught them how to ride horses and handle livestock, how to pit-roast goats for birria, and, most important, how to work. Here in rural Montana, he was raising his kids with buena educación—lessons in manners and values that he hoped would bring them success at school, on the farm, and anywhere else they might wind up.

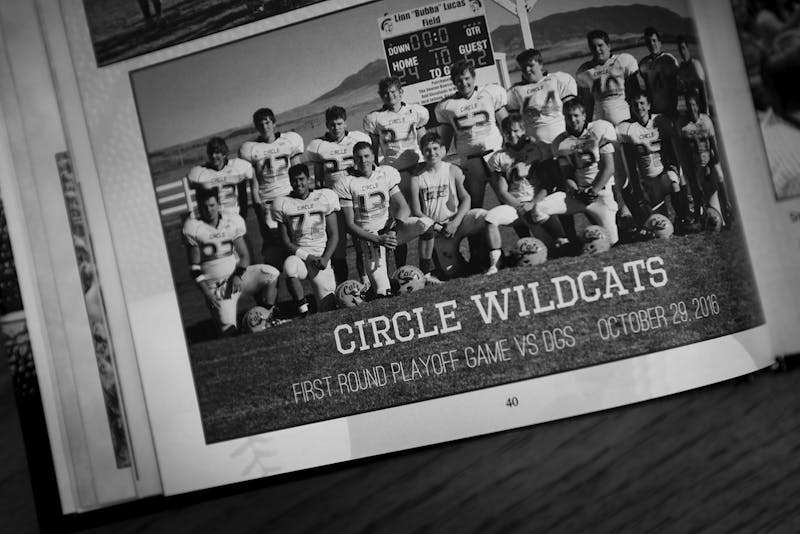

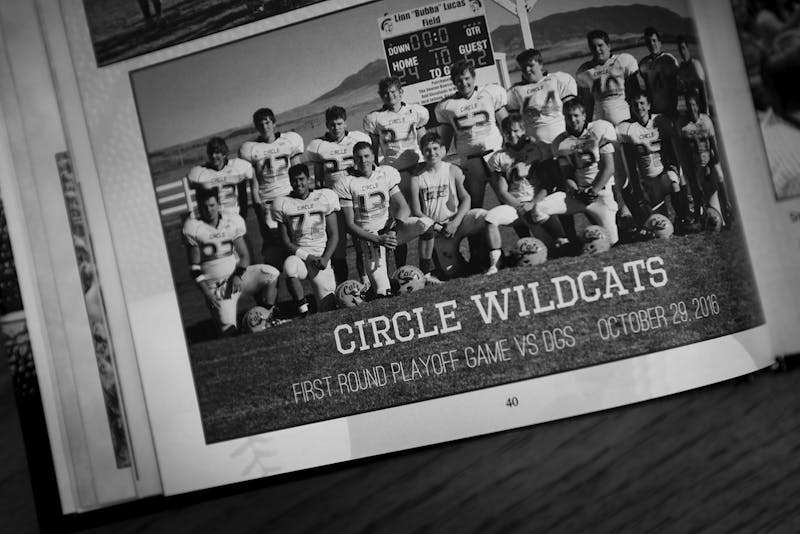

The Orózcos got along well with the ranch owners, Rob and Carla Delp. With one son off to college and only one still left at home, the Delps had even given their own ranch house to Audemio and Amparo and moved into a trailer next door. Their younger son, Brett, was in the same grade as Juan Luís, and the boys became best friends. They played on the Circle High eight-man football team and helped their fathers with chores after school. Audemio had a good friend of his own on the ranch—a man named Alejandro, who came up from Nayarit, Mexico, for a few months every year on a visa for temporary agricultural workers. Audemio liked having someone around to talk to in Spanish and drink a couple of cold beers with after a hard day’s work, even though Alejandro’s presence was a constant reminder of his own family’s peril. Unlike Alejandro, Audemio and Amparo were “undocumented,” or in Audemio’s words, “sin papeles.” In the official terminology of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement they were “illegal aliens,” and Audemio was already known to them.

Since his first crossing in 1993, Audemio had been arrested and deported multiple times, most recently in 2011. As a result, he was officially barred from reentering the country for 20 years, and he had received a final removal order, which meant ICE could arrest and deport him at any time. After his last arrest and detention, however, in October 2013, Audemio had been released, and he’d been living under an “order of supervision” ever since. The order of supervision allowed Audemio to continue to work and provide for his family while he waited for his attorney to determine if there was a legal remedy for his immigration case. He wasn’t required to wear an ankle monitor, as tens of thousands of people do under orders of supervision, so there was nothing in his daily life to remind him that he was living on borrowed time. The only significant burden was that he had to check in with ICE agents once a month in Billings. It was an obligation he never missed, though it meant traveling four hours by road or round-trip on a government-subsidized flight from Sidney. The check-ins had become so routine that Audemio grew confused about his immigration status. He knew he didn’t have a visa, but he did have a federal work permit, which included a government-issued photo identification card. And every month, he walked into the belly of the deportation beast, presented himself to the dreaded ICE, and then came right back out again. In his mind, he wasn’t exactly “illegal.”

As the years stretched on and the children grew older, Audemio occasionally allowed himself to imagine that he’d slipped into some kind of immigration limbo that might somehow last forever. On that bleary August morning in 2017, when he packed four of his kids into the truck and headed to Billings for his monthly check-in, the illusion was bolstered by an Obama administration policy that had effectively halted action on noncriminal immigrant cases like Audemio’s. At the height of enforcement in 2012, the Department of Homeland Security deported 419,000 people—a high-water mark that President Donald Trump has yet to surpass. The aggressive immigration enforcement during President Barack Obama’s first term brought him no closer to progress on immigration reform, but it did earn him the nickname “Deporter in Chief”—a stain on his mostly progressive image. In his second term, Obama sought to allay criticism from the left by instructing ICE to focus enforcement on “criminal aliens,” those who had committed felonies such as drug offenses, violent crimes, and driving under the influence. Under the new guidance, ICE mostly left noncriminal immigrants like Audemio alone, even if it knew where to find them.

Just five days into his term, Trump issued an executive order that essentially directed ICE to take action on all known undocumented immigrants, criminals and noncriminals alike. Critically, for Audemio, Trump’s order included a provision instructing ICE to focus enforcement on immigrants with final removal orders. Audemio’s family didn’t pay much attention to politics, but they had heard Trump’s harsh immigration rhetoric, and it made them nervous. Still, they didn’t know that in response to the president’s immigration policy directives, ICE was trying to “boost its sagging deportation stats by going after the easiest targets—in particular immigrants who show up for regularly scheduled ‘check-ins’ with ICE officers,” as The Washington Post reported that year. In the first seven months of Trump’s presidency, ICE arrested nearly three times as many noncriminal undocumented immigrants as they had in the same period of the previous year, more than 28,000 in total.

As the years stretched on, Audemio occasionally allowed himself to imagine that he’d slipped into some kind of immigration limbo that might somehow last forever.

Under the false security of the Obama administration’s enforcement priorities, Audemio had been able to see Juan Luís through high school, right up to the day he walked across the stage in a blue mortar cap with a silver tassel to accept his diploma. In a few weeks, Juan Luís would head off to community college in Miles City to study automotive technology. Audemio drove past Miles City that morning on the way to Billings, tracing the braided contours of the Yellowstone River on Interstate 94, neat plots of alfalfa on one side of the highway, sandstone and silt badlands on the other. Miles City wasn’t too far from Vida, and Juan Luís, 19, who rode shotgun, would be able to come home on weekends. Miguel, 15, Jessica, 13, and Audemio Jr., 8, rode in the back. (Karina, 17, his oldest daughter; Yajaira, 11; Brian, 4; and Brayden, an infant, were with Amparo.) When they pulled into the parking lot outside the federal building that housed the ICE office a little before nine, Audemio did something unusual. He took all the cash out his wallet and handed it to Juan Luís. The boy shot his father a concerned look. “What’s this for?” he asked. “You never know what’s gonna happen with these people,” Audemio said. Then he and Miguel got out of the truck and headed across the parking lot toward the building.

Juan Luís stayed with the two younger children. Not long after, he heard a tapping on the window and looked up to see two federal agents in plainclothes standing outside the truck. Miguel stood between them, sobbing. Juan Luís opened the door and stepped out. “Are you 18?” one of the agents asked. “Yes,” he replied. They asked Juan Luís to show his identification to prove his age, and since Miguel was a minor, they made Juan Luís sign a release form before they’d let the younger boy go with his brother. Once he was in the truck, Miguel told his siblings what had happened. Inside, ICE agents had told Miguel they needed to talk to Audemio alone. They brought Miguel outside the room where Audemio normally checked in, then closed the door behind him. He heard the locks click. “We’re going to deport your father,” one of the men told Miguel. “You’re not going to get to see him again, so if you want, you can say goodbye.” They let Miguel back into the room, where Audemio sat in handcuffs. Tears ran down Audemio’s cheeks as he hugged Miguel. “Don’t worry, mijo,” Audemio told the boy. “I’ll see you soon.”

It could be said that Audemio set his own trouble in motion, in 1993, when he paid a coyote $300 to help him cross the border outside Tijuana, as a 20-year-old seeking adventure and good pay in California’s fruit and almond orchards. He crossed back and forth between Mexico and the United States a number of times that year, and he says he was caught on eight occasions, but never officially deported. Things were different then. The consequences for getting caught rarely amounted to more than a free ride back to the border. For Audemio, as for millions of Mexican laborers, skirting the official immigration system was a way of life.

After about a year of border-hopping, Audemio returned to Michoacán with his earnings. He fell in love with a young waitress named Amparo Ángel, who worked at a restaurant in La Huacana. They were married, and soon after, Amparo gave birth to Juan Luís. Before Juan Luís’s first birthday, Audemio led his new family north on a two-day bus journey to Tijuana, where the couple paid a coyote $2,000 to guide them across the border. They had passed Juan Luís off to a couple who had visas, and who claimed the infant as their own as they went through the Border Patrol checkpoint at San Ysidro, California. Audemio and Amparo collected Juan Luís safely on the other side, joining millions of undocumented families living the shadow side of the American dream.

Over the ensuing decade, Audemio found work as an electrician, a mechanic, a fruit picker, a welder, and a tractor driver. Living in and around Merced, California, where Amparo gave birth to five of the couple’s children, the family blended easily with the large population of Chicanos and Spanish-speaking immigrants. But they were building a life on a fragile foundation, and in September 2011, whatever pretensions of security they had were shattered when ICE raided a field in Mariposa County where Audemio was working, sweeping him up along with several others and deporting him across the California border the same day. In the next six weeks, Audemio would be caught trying to cross the border three times, once with a counterfeit Mexican passport and B-2 tourist visa in the pedestrian lane at San Ysidro. (He had provided passport photos, signed official-looking documents, and paid almost $600 for the fake documents, which he believed to be real.) Following these four deportations in a short period, Audemio received his 20-year ban. With the removal orders on his record, he would probably never again have a case for legal immigration. For Audemio, this was a hassle, but not an insurmountable one. By early December, he’d found another hole in the border and was back with Amparo and the kids.

If there’s a precise date when things went irreparably wrong for Audemio, though, it was October 2, 2013. By that time, Audemio had moved his family—nine people—to Sidney, where he’d found work maintaining rental housing for oil workers on the

Montana-Dakota border. That morning, he was on his way to work, riding in the passenger seat of a coworker’s truck, when a Sidney police officer stopped the driver for speeding. The officer demanded Audemio’s identification, too, even though he had nothing to do with the traffic violation. Sensing the risk, Audemio protested as best he could in his halting English, but he eventually handed over an ID from Washington state, where he had been living with his family for a brief time before moving to Montana.

The officer retreated to his squad car, returning a few minutes later with a cell phone, which he handed to Audemio. A man on the other end began asking questions: Did Audemio have papers? Was he in the United States legally? The man let on that he was a Border Patrol agent, and Audemio confessed that he didn’t have papers. The Sidney officer detained Audemio until an agent from the closest Border Patrol station arrived to take him into custody. (California, Illinois, and many municipalities throughout the country have implemented policies that limit collaboration between local law enforcement and federal immigration authorities; other states, including Arizona, Alabama, and Georgia, have passed laws to give local law enforcement greater freedom to probe suspected immigration violations. As for the Sidney officer who questioned Audemio, he appears to have been operating outside of his authority. According to the Montana Immigrant Justice Alliance, “Local police or the Montana Highway Patrol are not immigration officers. They are not authorized by law to investigate or arrest people for their immigration status, and have no right to ask questions about your immigration status.”)

Border Patrol agents transported Audemio to two different jails over the course of two days, until he arrived late in the afternoon of Friday, October 4, at the Jefferson County Criminal Justice Center in Boulder, Montana, more than seven hours from Sidney. He was issued a pair of orange pants and an orange shirt, a gray blanket, a blue bedsheet, a towel and washcloth, and orange socks. As the jailer placed Audemio into a group cell called A-Pod, he told the nine inmates already in the cell that Audemio was an immigrant who was going to be deported. Audemio made his bed on the only empty bunk and took stock of his new companions. They scared him. He could understand a lot of English, but he couldn’t speak more than a few phrases. No one spoke Spanish in his cell, and neither did the two guards, who didn’t seem to be wearing official uniforms. The guards’ clothing confused Audemio. He couldn’t tell which agency they worked for or what level of authority they possessed. Likewise, he didn’t know that he was entitled under DHS regulations to be in contact with an immigration services organization, and no one told him so.

A couple of the men seemed to be leering at him, making lewd gestures and laughing. Perhaps, knowing that Audemio was about to be deported, they looked at him as an easy mark. One tall and scrawny man with a long neck appeared to be the group’s ringleader. Audemio sensed that the other inmates were afraid of him. Near bedtime, the skinny man asked the guards for a pot of coffee, which they brought. Audemio drank two cups, then filled a third, which he set down to drink after his shower.

When he returned from the bathroom, he finished his coffee and immediately felt drowsy. Soon he was fast asleep.

Audemio awoke in the middle of the night face down on his bunk, gasping for air, unable to move his legs or his arms. His legs were angled off the bed so that he was almost on his knees on the floor. Someone was on top of him, and he felt the painful sensation of being anally penetrated. He tried to get free, but they had his feet and hands pinned. He attempted to look over his shoulder at his assailants, catching only a brief glimpse of shadowy figures standing around the bunk before someone forced his face back into his pillow. He was asphyxiating and thought he might die. He suffocated and passed out without ever managing to scream.

The following morning, he woke fully dressed. There was an acute pain in his abdomen and he could feel moisture in the seat of his pants. He felt groggy, suddenly certain that someone drugged his coffee the night before while he was in the shower. In the bathroom, he felt what he assumed to be semen drain from his rectum. He didn’t tell anyone what had happened, because, as he later told investigators, there was no one he trusted enough to tell: No one spoke Spanish, and the guards seemed as afraid of the inmates as he was.

For two more days in A-Pod, Audemio waited out the nights sitting up in his bunk with his back to the wall, clutching sharpened spoons in each of his fists.

Before his rape, Audemio was certain to be deported. He did not even have the right to see a judge because of his prior removal order. But the sexual assault made him eligible for a special category of visa for crime victims. The U Visa, created as part of the 2000 Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act, is intended to help law enforcement investigate human trafficking, sexual assaults, domestic violence, and other mostly violent crimes. The idea is simple: Protecting undocumented immigrant victims and their families from deportation makes them more likely to assist law enforcement, which makes it more likely that criminals will be caught. Audemio would have been a strong candidate to secure a U Visa in 2013—or at least a spot on the waiting list, which now numbers 128,000 people—if Jefferson County authorities or ICE had been willing to certify his application. They refused.

The hitch was that in order for a U Visa application to be completed, a law enforcement official must fill out a “certification” form attesting that the applicant has been the victim of a qualifying crime, has information that could be useful to investigators, and is cooperating in the investigation. In the case of a person escaping a sexual trafficking ring or of a domestic violence victim, the relationship between victim and law enforcement is straightforward—but what happens when a crime occurs under the protection of the would-be certifying agency, as it did in Audemio’s case? If Jefferson County had certified Audemio’s U Visa application, it would have admitted, indirectly, that a rape occurred in its jail. This would have been an admission of failure to follow the protocols of the 2003 Prison Rape Elimination Act, which includes a stated “goal of keeping separate those inmates at high risk of being sexually victimized from those at high risk of being sexually abusive.” (Inmates “detained solely for civil immigration purposes” can be considered high risk according to the PREA criteria. Notably, two of the inmates in Audemio’s pod were convicted felons who had been forced to enroll in the state’s violent or sexual offenders registry.) ICE would have further had to admit that it contracts with jails that cannot guarantee the safety of immigration detainees, despite implementing a “zero tolerance” policy years before to prevent such incidents and to penalize contract facilities that do not meet the agency’s standards. Not only did officials from Jefferson County and ICE refuse to certify Audemio’s U Visa application, they denied the rape ever happened.

Audemio didn’t report the rape until three days later, when he got to another ICE way station in Rigby, Idaho. A Spanish-speaking ICE agent named Blanca Chapa was sufficiently concerned that she immediately sent him to the Eastern Idaho Regional Medical Center, where a nurse gave him a sexual assault interview and a physical examination. She measured Audemio’s pulse at 122 beats per minute—about what you’d expect for a fit person like Audemio after a few minutes of jogging. Using medical shorthand, she wrote, “Pt is tearful, appears embarrassed, looks at his hands and floor during interview.” She wrote that Audemio’s symptoms—tenderness and inflammation in his anus—were “consistent [with] rectal penetration.”

For two days in A-Pod, Audemio waited out the nights sitting up in his bunk with his back to the wall, clutching sharpened spoons in each of his fists.

The nurse handed her report, bloodwork, digital photos, and swabs from Audemio’s genitals and rectum under seal to an ICE detective, who sent these by next-day UPS to the Jefferson County Jail. That same day, ICE contacted the Jefferson County authorities to inform them of the incident. The jailers were able to retrieve Audemio’s still-unwashed clothing and bedding, which may have contained critical DNA evidence from Audemio’s attackers. They told the Jefferson County sheriff—who had officially opened an investigation—that they would review the security camera footage from the entirety of Audemio’s stay.

On October 10, Audemio was transferred back to Montana, where he passed through an ICE office in Helena en route to the Cascade County jail. At the ICE office, a Jefferson County investigator and an ICE agent interviewed him, with Blanca Chapa translating via speakerphone from Idaho. They kept Audemio in handcuffs, as if he were the suspect and not the victim. Describing his rape, Audemio broke down and cried. He asked for the attorney he’d hired with help from the Mexican Consulate in Boise, Idaho, but the officers told him his attorney was unavailable.

This was not true. In fact, Shahid Haque, a Helena, Montana-based immigration attorney, was in the building, but was not allowed to see Audemio until after the interview ended. Amid the ensuing media coverage of Audemio’s case—the alleged sexual assault of a deportee while in government custody was newsworthy—there was speculation that Audemio made up the rape story for the purpose of securing a U Visa. Haque told me Audemio didn’t even know what a U Visa was when he reported the incident. At the time, his most urgent concern was getting the HIV prophylactics that had been prescribed for him in Idaho.

A week later, Haque secured Audemio’s release on the order of supervision. In the following months, Audemio repeatedly offered to assist in the investigation—to look at mug shots or a lineup, to comment on testimony from his cellmates—but he would not hear from the investigators again. Still more concerning, when Haque acquired the security camera footage through a court order, he found there were gaps on the night of the assault totaling nearly three and a half hours, including a two-hour block from 2:13 to 4:10 a.m. that coincided with Audemio’s estimation of when the rape occurred. Jefferson County Attorney Matthew Johnson—who fought Haque’s efforts to obtain the evidence, on the grounds that releasing it would jeopardize the pending investigation—said the gaps resulted from motion-sensitive cameras turning off when there was no activity in the cell. “When the video skips,” Johnson said in an email to Haque dated November 7, 2013, “it is because there was no movement for a period of time.” This was a red flag: The video from Audemio’s pod cuts out for the first time at 10:30 p.m., while people are still milling around and very much awake.

Haque became concerned that Jefferson County was engaged in a cover-up. Hoping that public exposure would force Jefferson County’s hand, Haque turned over the footage to John S. Adams, an investigative reporter for the Great Falls Tribune, who contacted the manufacturer of the jail’s security cameras. In his subsequent article, Adams wrote, “a Pelco technical support specialist . . . said it doesn’t make sense that the motion-activated DVR would stop recording on its own when motion is clearly visible.” In other words, Johnson’s explanation for the gaps made no sense, and though he would later supply Haque with more video to fill in some of the gaps, he was never forced to supply the footage from the critical 2:13 a.m. to 4:10 a.m. window.

Amparo worried about her own status, given the Trump administration’s clear willingness to separate undocumented parents from citizen children.

For a year and a half, Audemio and Haque waited for the results of Jefferson County’s investigation, hoping, at the very least, for an acknowledgment of the crime that would compel the county or ICE to certify Audemio’s U Visa application. In 2015, with the investigation seemingly shelved, Haque filed a civil suit alleging that Jefferson County had violated Audemio’s constitutional rights by detaining him punitively and in unsafe conditions, causing him to suffer “serious and severe emotional distress.” Two weeks later, as if on cue, Johnson finally emailed Haque with the investigation results: “My review of this case concludes that there is not sufficient evidence to support the allegations of [Audemio],” he wrote. “The investigation and a second investigation by Homeland Security”—DHS had cooperated in Jefferson County’s investigation and conducted an investigation of its own—“conclude that there was no cover up, videos were not deleted nor blocked out, and a crime was not committed against [Audemio]. Therefore, the case will be closed.”

Nevertheless, in November 2016, a few weeks after Trump’s election, Jefferson County agreed to pay Audemio a $125,000 settlement, although without having to admit to any liability for the assault. “That to me is an indication they knew they did something wrong,” Haque told me this past May at his office in Helena. As we talked, he occasionally dragged on an e-cigarette, exhaling clouds of vapor into the room. His work on behalf of immigrants had earned him an award from the American Civil Liberties Union the year before, but it had also drawn vitriol from right-wing groups who attacked him online and, occasionally, at public rallies. He seemed wearied by the work, and by the invasion of his privacy, but also defiant. “I can’t believe that our system allowed all of this to happen and then deported him, and there was no one along the way who helped him at all, in the entire system,” he said. “It’s shameful that they could pay $125,000 but they couldn’t just sign this U Visa. They couldn’t just admit that this happened to him.”

Audemio and Amparo and their large family initially lived together in a trailer in Sidney, Montana.

Audemio and Amparo and their large family initially lived together in a trailer in Sidney, Montana.Not long after Audemio’s arrest, Amparo fled Montana for another state with six of the kids, leaving only Karina and Juan Luís behind. With Audemio locked up in an ICE contract detention facility in Aurora, Colorado, she was left to worry about the publicity from his arrest and her own undocumented status. Staying in the same place might bring ICE to her doorstep, and then what would her children do? The Trump administration had made it clear that it would not hesitate to separate undocumented parents from their citizen children.

Karina had gotten pregnant during her sophomore year of high school. When she was 16, she gave birth to a daughter, and now she was living on her own in Sidney with her boyfriend, who worked in the oil fields. Juan Luís suddenly found himself alone. He was 19, and still undocumented, though Shahid Haque had managed to get him enrolled in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which would shield him from deportation until at least November 2019.

Taller than Audemio, and shyly handsome, with a light mustache that did not make him look a day older than his 19 years, Juan Luís had just emerged from the best year of his life. His football team had a great season, he’d done well in school, he had a large group of friends, and he even took a pretty girl to the prom. But Juan Luís was disturbed to see how many of the kids from school supported Trump’s virulent anti-immigration rhetoric. “It hurt. I heard a lot about, you know, ‘Get the illegals out of here . . . build the wall.’ I mean, it was kind of intimidating,” he told me in July, at Karina’s house in Sidney. Hearing people talk that way in the small town where he thought he was accepted made Juan Luís feel painfully out of place for the first time in his life. “Ever since Trump came in, all these people who were hiding in the shadows, the racist people—you never thought you’d see so many,” he said. Toward the end of high school, Juan Luís had considered joining the Montana National Guard, but his growing awareness of racism in his community soured him on the plan. “I wanted to go fight for this country, but then this shit goes down,” he said, “and you just kind of retaliate against it. You don’t want to fight. They don’t deserve you.”

Thinking his father would be back soon, Juan Luís decided to go ahead with his plan to move to Miles City for school. A family friend helped him find a place to stay and buy the tools he needed for his mechanic classes. Juan Luís had learned everything he knew about cars from Audemio, who could swap out whole engines and diagnose problems just by listening. Audemio could do these things despite never having any formal training. He seemed to be able to do almost anything, from breaking a colt to rewiring a house. But sometimes Audemio’s lack of education got in his way, as when he had to run farm machinery with complex computer systems. Audemio was always telling Juan Luís to take his education seriously—after all, the chance to give Juan Luís the opportunities he’d never had was what motivated Audemio to bring him across the border in the first place. Settled in at school, Juan Luís tried to concentrate on his classes, but as the weeks sped by without any promise of Audemio’s release, he grew anxious about his mother and his siblings. “I wanted to get a good career going,” he told me. “Just, everything was going downhill, so that’s when I decided to just leave college and help out the family.”

Juan Luís joined Amparo and the kids in the resort town where she had found work cleaning rooms. As it turned out, there was a position available at the same resort for a maintenance technician. Even though Juan Luís had no significant work experience, he was able to prove that he could handle electrical work and anything else they might need him to do. Once on the job, he immediately realized how much his dad had taught him, and he felt the pain of his absence acutely. “I never actually thought I’d be set in the place like I am now,” he told me, “pretty much playing the role of my dad, because I’m trying to teach my siblings the good and the bad.”

Miguel, who was 15, was having a hard time at his new high school, which was bewilderingly large compared with the tiny country school back in Montana. Along with the usual social pressures of adolescence, there were gangs. He begged Amparo to let him be home-schooled, and eventually she gave in. But Amparo didn’t speak much English, and whenever she wasn’t working to cover the $1,300 rent, she had six other kids vying for her attention. With a full-time job of his own, there wasn’t much Juan Luís could offer Miguel during the school day either, but he did his best to help however he could. Putting his own future aside, Juan Luís stayed with Amparo and the kids through the winter and into the spring, earning $18 an hour, and turning most of his paycheck over to Amparo. Together, they waited for news from Colorado, where Audemio was still detained.

Juan Luís had considered joining the Montana National Guard after high school. “But then this shit goes down,” he said. “You don’t want to fight. They don’t deserve you.”

It was in Colorado that I first met Audemio, at the ICE detention facility in Aurora, in February 2018. He was dressed in prison scrubs, sitting in a small meeting room with a table and a couple of chairs and concrete block walls. His thick arms and strong hands bore evidence of years spent fixing fences and working with livestock, a life lived on two feet and out of doors. Squat and powerfully built, he had a thin black beard that matched dark eyes rimmed in blue. He gave me a firm handshake without any bluster. As we talked, he stared at the floor, mumbling his answers, occasionally losing his train of thought, as if on the verge of sleep. Seven months in prison had exhausted him, and the sheaf of papers in a manila folder in his lap seemed a source of as much confusion as clarity. Among the documents was a six-week-old order for Audemio’s release, once he made a $3,500 bond payment, which should’ve allowed him to await the final decision on his case at home with his family. And yet, here he was behind bars. After the Border Patrol reinstated his final removal order in October 2013, Audemio had never had much legal recourse. A last-ditch asylum appeal filed by a new attorney didn’t seem to be going anywhere. He was likely to be deported any day.

A little over a year before, he’d been standing on the sidelines at the district football finals, beaming with pride and awe as an entire Montana town erupted in cheers for Juan Luís, who had just sacked the opposing quarterback for the third time. On nights like that, he experienced a feeling of momentary perfection. He had come a long way from Michoacán, from his days of picking almonds by hand, from that fetid trailer in Sidney. He even had his own boat, which he towed up to the Fort Peck Reservoir on the weekends so that the kids could swim. He also had bought a horse, outfitted with a Mexican-style saddle that he ordered custom from Jalisco. He named the horse Blacky, and whenever he rode him, he wore a cowboy hat with a leather band embossed with the word El Jefe. Audemio didn’t tell the kids in so many words, but they knew Blacky helped their dad heal after the trauma of his rape. He loved that horse, and he loved living on the Delps’ ranch, for one reason above all the others: His only real dream was to be together with his family, in America, where after decades of struggle he’d finally made the life for them that he’d always dreamed of.

When I asked Audemio how it felt to be away from Amparo and the children, his head dropped and he began to cry. He said he managed to talk to them for a couple of minutes almost every day, but he was worried about them and desperately lonely. “I can’t handle being away from them,” he said. I asked him what he planned to do if he were deported. He shrugged and shook his head. Under his breath, he said, “I’ll just come back.”

A little over a month later, on April 10, 2018, Audemio Orózco Ramirez was deported to Mexico.

On a sunny July evening in Morelia, the capital city of Michoacán, I met Audemio at an apartment I’d rented in town. A Zumba class was finishing up in the park across the street. The instructors led the workout from a raised stone platform beneath statues of soldiers from the Mexican Revolution. Audemio was wearing a plain blue T-shirt and a Montana State University ball cap, jeans, and square-toed cowboy boots. He looked as Montana as they come, ready to straddle a barstool in a dusty saloon or grab a pair of fencing pliers. He’d been in Mexico for three months, and he appeared healthy and tan, barrel-chested, maybe even working on a slight paunch. His scruffy beard was gone, replaced by a neatly trimmed goatee. We sat down at the small table in the kitchen, and over a few beers, we talked about his life, the shock of reentry into Mexico, the anguish of being separated from his family, and his plans for the future.

Audemio spent the formative years of his childhood on a cattle ranch that his father inherited from his parents, who came to Mexico in the 1930s to escape the Spanish Civil War. The ranch is near Ario de Rosales, about two hours southwest of Morelia. Education was not a priority for the family, since the boys were expected to work, and Audemio never learned to read well, but he liked ranching and it was a picturesque childhood. It was not without hardship, though. When he was a teenager, his father took up with another woman and forced Audemio and his eight siblings, along with their mother, Oliva, off the ranch. The children moved with Oliva to Uruapan, where she provided for them by taking in sewing. Years later, Audemio and his older brother Roberto tried to patch things up with their father, but he had sons with his new wife, and it was clear there would be no inheritance for them. So, like so many millions of Mexicans of his generation without many options, Audemio left for the north and the promise of seemingly limitless opportunity al otro lado: on the other side.

In Audemio’s long absence, Michoacán had grown terrifyingly violent. Just a couple of months before Audemio was deported, one of Amparo’s younger brothers was kidnapped in Ario de Rosales. He was a construction worker and had nothing to do with the cartels, but one of the gangs had apparently kidnapped him because he was from a rival village, thinking he was a spy. The attackers mutilated him, beheaded him, and dumped him in the street. Then they sent photos of the corpse to his family, and the pictures made it all the way to Sidney, where Karina showed them to me when I visited.

This was the Michoacán that Audemio had returned to, the one he had feared during all of his months in detention. Here, family was your only protection, and Audemio had almost no one. Of his seven living siblings—Roberto died in a car crash in the United States—only one brother, Martín, remained in Michoacán. Martín had also lived for many years in the United States, mostly working construction in Utah, but he’d been deported after serving time in prison on drug charges. Now he owned a taco shop on the outskirts of Morelia and was thinking about getting into the avocado business. Martín and Audemio got along, but they barely knew each other. Their father was still in Ario de Rosales, but the elder Orózco had little to offer his sons in terms of work, protection, or shelter. His children from his second wife were doing drugs and hanging around the wrong people, and it was best to steer clear of them.

“It’s pretty strange to be here,” Audemio told me. “Just yesterday I got a call from the sicarios”—cartel hit men—“and it doesn’t make me feel good to be receiving those calls.” A local gang in Ario de Rosales had accused Audemio of working with the police on behalf of a rival gang to identify their members, and now their hired guns were calling to warn him. Audemio was bewildered. “When I was here before, there wasn’t any of this organized crime stuff,” he said. Now, he was seeing bodies in the gutters, hacked by machetes, or cut up and stuffed into trash bags and thrown in the street. “The people don’t say anything about what they see,” Audemio said. “They see, but they know nothing.”

Audemio wasn’t working. The one time he had tried to earn some money by helping a friend move avocados, the truck they were driving got hijacked by gangsters bristling with AR-15s and AK-47s. “They had grenades and everything,” Audemio said. Although Morelia had in recent years made great strides to improve security in the city, the countryside was still at war, and gangster militias operated in plain sight, driving in convoys of cars with blacked-out windows and no license plates. Meanwhile, in the countryside, police often wore masks out of fear they’d be recognized and their families would be murdered. Many police units were either on the take, or terrified to get down from their trucks, or both. A few hours away, in the town of Ocampo, state police had recently arrested 30 municipal police officers for helping to carry out the assassination of a mayoral candidate—one of 132 candidates murdered in the recent elections. After so long in the United States, Audemio was not cut out for the daily stress and danger of navigating the Michoacán countryside. He had temporarily moved in with Martín, and he was planning to leave for the border as soon as possible.

“I miss my family,” he sobbed, taking a few minutes to collect himself. “I’ve never been far from them until all this happened to me.” He was especially devastated to be away from his infant son, Brayden, who was born in Montana in 2017. “He was only 6 months old when they arrested me.” Worst of all was the shame of being unable to provide for his wife and children. Audemio’s life was defined by his role as a hardworking family man. The settlement money was gone. He’d purchased a truck for himself with the money and another for Juan Luís’s high school graduation present. The rest went to pay attorney fees for a failed last-minute asylum case and to cover the family’s expenses during his time in detention. Now he was in the uncomfortable position of having to ask friends and relatives for loans.

Despite having been warned multiple times back in 2011 that he was banned from reentering the United States, Audemio was still baffled by his deportation. “I never thought they were going to throw me out, because when they gave me the papers”—the work permit and order of supervision—“they told me that if I never committed any crimes, I’d never have any problems. It wasn’t until the new president was inaugurated that they made the law to take away papers and deport people. That’s when they grabbed me,” he said. Referring to the monthly check-in on the day of his arrest, he said, “If I had known what was going to happen, I never would’ve shown up again. I would’ve gone to another state, and they wouldn’t have done anything, just like when someone comes to a country illegally and there’s no record.”

Audemio says he was raped by inmates in his jail cell in the Jefferson County Criminal Justice Center.

Audemio says he was raped by inmates in his jail cell in the Jefferson County Criminal Justice Center.Other than his unacknowledged rape, Audemio’s story is tragic only in its ordinariness. As far as immigration cases go, his is not complicated: He had crossed illegally multiple times, was caught and deported multiple times, and in the process, he lost his right to a hearing before a judge. Considered in this light, it’s surprising that Audemio made it as long and as far as he did in the United States. There are approximately eleven million undocumented immigrants living in the United States—roughly one in every 30 people, and one in every 15 in the labor force—a number that has not changed much in recent years and may be declining. The aggressive enforcement of the Obama years, now redoubled under Trump, seems, in cases like Audemio’s and many more, to have caused incalculable suffering—while offering no measurable benefit.

Among Mexicans, legal and illegal immigration rates have dropped rapidly over the last decade. There were over one million detentions along the U.S.-Mexico border in 2005; by 2014, that number had fallen to fewer than 230,000. Immigration researchers attribute the decline to a variety of factors, including more effective border security under Bush and Obama, declining birth rates in Mexico, and the lingering effects of the Great Recession and growth in the Mexican economy. No matter the cause, the illegal immigration crisis that Trump and right-wing Republicans crow about simply doesn’t exist. What does exist is a generational failure to reform the American immigration system to ensure that people like Audemio are able to live and work in the United States without getting caught up in an expensive, traumatic, and ultimately futile enforcement apparatus.

This failure exists alongside an economy that benefits from $11.6 billion annually in undocumented immigrants’ tax payments and spending. Putting a dollar value on undocumented immigrant labor is extremely difficult, but California’s controller estimates that undocumented workers’ labor represents $180 billion a year to the state’s economy—approximately equivalent to the 2015 gross domestic product of Oklahoma. It’s worth noting that California, frequently the target of attacks by Trump and right-wing Republicans over its sanctuary cities, is home to 21 percent of all undocumented immigrants. The position of the George W. Bush Presidential Center in Dallas, Texas, founded by the Republican president, shows how transformed the GOP has become in recent years on the issue. The center advocates strongly for the immigration overhaul that Bush called for during his presidency, claiming, “Nearly 11 million undocumented immigrants and their families live and work in the U.S., contributing significantly to our economy. Deporting all of them is impractical, expensive, and inhumane. A reasonable solution allowing law-abiding undocumented immigrants to live and work here legally is imperative in any serious immigration reform.” As for temporary agricultural visas, which Audemio could have benefited from, the center’s web site says, “The caps are too low to meet market demand. The process is too burdensome to make using the legal visa system worthwhile.”

No wall, no fine, no threat of imprisonment, no “deterrent” policy, however draconian, would ever prevent Audemio from attempting to rejoin his loved ones.

Meanwhile, in an era of falling crime, the private prison industry has been quick to seize on the growth potential in the immigrant detention market. GEO Group, which operates the Aurora facility, is the largest private prison company in the country, one of several contracted by the federal government to house thousands of immigration detainees awaiting court dates, deportation proceedings, or both. GEO gave hundreds of thousands of dollars to pro-Trump organizations in the 2016 election and donated $250,000 for his inauguration, undoubtedly encouraged by Trump’s “Build the Wall!” slogan and his pledges to crack down on immigration. Trump delivered: In 2017, his first year in office, ICE projected an increase in detainee beds of 26 percent, to 51,000, with the overwhelming majority in private facilities like the one in Aurora. All told, ICE spends between $2 billion and $3 billion on immigrant detention annually, at an average daily cost of about $208 per bed. For Audemio’s stay at the Aurora detention center, where he was housed for nearly eight months, ICE would have paid GEO about $51,000. On average, it costs taxpayers about $213,000 to detain, prosecute, and remove a single undocumented immigrant, according to the Bipartisan Research Center.

While arrests of suspected undocumented immigrants have spiked under Trump, deportation rates have actually decreased, in part because the immigration courts are disastrously overburdened. According to the most recent data compiled by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse immigration project at Syracuse University, there is currently a growing backlog of 768,00 cases—an increase of more than 220,000, or nearly 40 percent, since the end of Obama’s term. That means immigration detainees are spending more time behind bars, awaiting their day before one of the country’s roughly 400 immigration judges, each of whom now faces an average docket of more than 1,700 cases per year. In a given year, judges complete only about 35 percent of their caseload—which means that even if no new cases are added, it will take years to get through the existing ones. The Bipartisan Research Center estimates that the current backlog won’t be cleared until 2040. Doubling the number of new immigration judges to the bench would clear the docket by 2019, at a cost of $400 million—less than 2 percent of the $25 billion border wall price tag.

Removing undocumented immigrants does not deter them from returning, even when the penalties are severe. Noncriminal detainees who reenter after a formal removal can face fines totaling thousands of dollars and up to two years in prison; those with multiple misdemeanors or aggravated felonies face prison sentences up to 20 years. So why do they do it? Why go back, again and again, despite the risks, despite the consequences?

Most often, the main reason, more than any other, is family. According to a 2016 study at the University of California, Davis, “being apart from families in the U.S. is the most significant factor influencing the deportees’ intent to return…. Deportees with a spouse and dependent child are four times more likely to intend to return than those without families in the U.S., despite the serious penalties if caught.” Extrapolating the findings to the nearly 80,000 parents of U.S.-born children deported in 2011, the study calculated that “between 18,676 and 31,126 will return without documentation to rejoin their families.”

And that, finally, is the most tragically ordinary aspect of Audemio’s story—the dimension that connects him most firmly to the country he has struggled to live in and that has finally rejected him. Audemio’s deep drive to make a family and to remain together with them as one is something that no American could fail to recognize as the same as his or her own. No wall, no fine, no threat of imprisonment, no “deterrent” policy, however draconian, would ever prevent Audemio from attempting to rejoin his loved ones. When we spoke in Morelia, he told me flatly that he had no intention of remaining in Mexico. “I’ve lived in a lot of places. Montana is the only place I want to live,” he said. He was planning to leave for the border the next day.

Juan Luís, a football player in high school, dropped out of community college to earn money for his family after Audemio was deported.

Juan Luís, a football player in high school, dropped out of community college to earn money for his family after Audemio was deported.The following morning, Audemio and Martín came to pick me up for lunch. He brought a big plastic suitcase he’d woven from trash bags and chips bags in prison, filled with trinkets he’d made from the same materials to bring to his family. Inside, there were little boots, cowboy hats, and intricate little saddles complete with neatly coiled ropes, tiny plastic machetes, and fringe. “How’d you know how to make this stuff?” I asked him, impressed by the workmanship. “Lo inventé,” he said.

I made it up. We got in Martín’s Honda Civic and went to eat birria at Martín’s favorite place, where the abuela working the comal knew him and brought us sweet corn tortillas two at a time as soon as they were done. Afterward, we went for a michelada at a hip place with lacquered plywood tables and tamarindo-candy-coated straws. Audemio, with his shirt tucked in, wearing a giant belt buckle, his duffel bag on his shoulder, seemed happy.

There didn’t seem to be much to celebrate. Audemio faced a bus ride of more than 30 hours through cartel country. At any point along the way, he could be yanked off the bus and robbed, or worse. His heavy Michoacán accent would make him suspicious once he left the state. If he made it to the border, he’d have to find a coyote, and then he’d have to cross, and then what? He would rejoin Amparo and the kids, he said, and get his old job back. He seemed confident. “I’ll see you in Montana,” he said, gripping my hand tightly.

The next evening, 1,500 miles north, in Tijuana, Audemio was held up at knifepoint by three men who took everything he had except his cell phone, which he’d left in the room where he was staying. He was carrying $5,000 cash, mostly

borrowed money, because he was planning to look for a coyote and figured he ought to be ready to pay on the spot. “They had a knife to my throat before I even saw them,” he told me. “Me robaron todo.”

Mientras las tormentas

eléctricas azotaban la pradera en el este de Montana poco después de las siete

de la mañana del 2 de agosto de 2017, Audemio Orózco Ramirez ya había estado despierto

y conduciendo hacia el sur por un par de horas. Estaba haciendo el viaje de

cuatro horas a Billings desde Vida, el pequeño pueblo donde había estado

trabajando como trabajador de rancho por casi cuatro años. Audemio, en ese entonces

44, y su esposa, Amparo, 37, vivían en un rancho, dentro de una casa de un solo piso

con un porche amplio. Con ocho niños en la casa, apenas cabían, pero ellos habían

soportado peores condiciones en las dos décadas desde que habían cruzado la

frontera por San Diego juntos con su hijo, Juan Luís. Antes de este trabajo,

habían vivido en un remolque desmoronado en Sidney, Montana, a la vista de un área

de ganado. Era marginalmente mejor que las chozas donde dormían los

trabajadores migrantes cuando solían venir de México para desyerbar los campos

de remolacha azucarera. No tenían ni una hoja como sombra, y el sol solía

convertir el remolque en un horno. El agua, que no se atrevían a beber, salía de

la llave con color café.

En Vida, los niños tenían todo un rancho para caminar, como Audemio cuando era niño en Michoacán. En aquel entonces, Audemio y sus hermanos escalaban las montañas que se disparaban hacia el cielo desde la cima del bosque. Cazaban javelinas y codornices y se comían los mangos de los árboles. Audemio se sentía orgulloso de poder recrear un pedazo de su infancia para sus hijos. Les enseñaba a montar caballos, a manejar ganado, a asar chivos para la birria y, más importantemente, a trabajar. Aquí, en la zona rural de Montana, estaba criando a sus hijos con buena educación, con lecciones sobre los valores que él esperaba que les trajeran éxito en la escuela, en el rancho y en cualquier otro lugar.

Los Orózcos se llevaban bien con los dueños del rancho, Rob y Carla Delp. Con un hijo en la universidad y el otro en casa, los Delps incluso le habían dado su propia casa a Audemio y Amparo y se habían mudado a un remolque al lado de la casa. El hijo menor, Brett, estudiaba en el mismo grado que Juan Luís, y los dos chicos se habían convertido en muy buenos amigos. Jugaban en el equipo de fútbol americano de Circle High School y ayudaban a sus padres a trabajar cuando salían de estudiar. Audemio tenía un buen amigo en la finca: un hombre llamado Alejandro de origen de Nayarit, México que venia por unos meses cada año gracias a una visa para trabajadores agrícolas temporales. A Audemio le gustaba tener a alguien con quien conversar en español y tomarse un par de cervezas frías después de un largo día laboral, aunque la presencia de Alejandro era un recuerdo constante del peligro que su propia familia corría. A diferencia de Alejandro, Audemio y Amparo eran “indocumentados”, o en palabras de Audemio, “sin papeles.” Bajo la terminología oficial del Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas, eran “extranjeros ilegales,” y Audemio ya estaba bajo su supervisión.