Christmas is often described as the season of mercy, forgiveness, and redemption. For a handful of prisoners each year, that description has even greater meaning. Governors traditionally use the holiday season as a thematic backdrop for pardons, and last month was no different.

Michigan Governor Rick Snyder issued one for Lukasz Niec, a legal immigrant who faced deportation by ICE for two misdemeanor convictions when he was a teenager in the early 1990s. Tennessee’s Bill Haslam pardoned seven people in the state’s prisons and reduced the sentences of four others. Arkansas’ Asa Hutchinson wiped away 14 people’s convictions and reduced a prisoner’s sentence to make him immediately eligible for parole.

Governors in most states have the power to pardon or commute sentences, either at their sole discretion or with some level of input from a commission. Since most convictions occur at the state level, some governors can wield even greater influence on criminal justice than the president can. But most governors rarely use this power, and few have made it a mainstay of their tenure in office—a major missed opportunity for justice and the public good.

Some outgoing governors were particularly resistant. New Mexico Governor Susana Martinez, a former prosecutor, issued only three pardons during her two terms in office and added new restrictions to deter applicants. Florida Governor Rick Scott turned the state’s clemency system into a hopeless slog. Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker issued no pardons during his eight years in power, and in one of his final official acts, he signed a bill requiring state officials to keep a list of pardoned people who commit subsequent crimes and the governor who pardoned them.

All three of those governors hail from the Republican Party, which traditionally favored tough-on-crime policies. But even Democratic governors can be stingy. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo made headlines last month when he pardoned 22 immigrants who faced deportation or couldn’t apply for citizenship because of previous state convictions. The pardons gave Cuomo a chance to cast himself as a leading figure in the Democratic resistance to President Trump. But with almost 200,000 New Yorkers in prison, probation, or parole, issuing fewer than two dozen pardons is hardly a courageous act.

Pardoning incarcerated people or commuting their sentences largely fell out of vogue during the tough-on-crime era at both the state and federal level. Harry Truman issued more than 1,900 pardons during his tenure, while Dwight D. Eisenhower handed out more than 1,100 throughout his eight years in office. That number fell even as prison populations exploded in the 1980s and 1990s: George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush collectively issued fewer than 700 pardons during their quarter-century in power. Though comparable figures for the nation’s governors aren’t readily available, they’ve reportedly shown a similar aversion to clemency since the 1960s.

What would it look like if governors pursued a more aggressive approach to their clemency powers? Jerry Brown, California’s outgoing governor, carved out a model of sorts. The state’s longtime leader spent his fourth and final term in office setting a national benchmark for clemency: The Times of San Diego reported that Brown has pardoned at least 1,332 inmates since 2011, quadrupling the number issued by the preceding four governors combined. The burst of activity is particularly stark compared to his two immediate predecessors, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Gray Davis, who respectively issued fifteen and zero pardons.

Those who have received pardons from Brown cut a broad swath, ranging from a couple that lost their home in the devastating Camp Fire last month to five Cambodian-born immigrants who feared deportation by the Trump administration. In a slate of Christmas Eve pardons, the governor also ordered new DNA tests for Kevin Cooper, a death-row inmate who says that local police framed him for a quadruple homicide in the 1980s. For Brown, there’s a self-redemptive element at play. He previously served as California’s governor from 1975 to 1983, right at the cusp of the nation’s turn toward harsher sentencing laws and mass incarceration.

Solid-blue states aren’t the only ones where governors have made bold use of their clemency powers. Terry McAuliffe, a moderate Democrat who led Virginia from 2014 to 2018, initially tried to restore voting rights to almost 200,000 former felons with a single executive order in 2016. After the state supreme court struck down his sweeping order later that year, McAuliffe began to issue them on a person-by-person basis, restoring the franchise to more than 173,000 citizens by the time he left office. Ralph Northam, his successor, has continued the clemency program on a rolling basis as prisoners return to society.

Issuing mass pardons may not be as politically feasible in some states as it is in California and Virginia. So where could a more apprehensive governor begin? Perhaps the most prudent place would be the swelling numbers of elderly prisoners who were condemned to spend their dying years behind bars. In a December 2017 report, the Vera Institute for Justice found that roughly 10 percent of prisoners in state custody in 2013—roughly 131,000 people—were more than 55 years old. Demographic trends are expected to raise that figure to 30 percent by 2030. Multiple states already have compassionate-release programs for elderly or dying prisoners; governors could fast-track pardon and commutations to accelerate the process.

Death row is another area where governors could be more aggressive. Thirty states currently authorize the death penalty, but only a handful of states regularly carry out executions. The growing difficulty in obtaining legal injection drugs, the decline in public support, and the expensive appellate process have made it a costly, burdensome proposition. The result, as a federal judge in California put it in 2014, is better understood as “life in prison, with the remote possibility of death.” Rather than continue to spend exorbitant sums on legal challenges and new execution methods, a governor could turn prisoners’ de facto life-without-parole sentences into actual ones.

There’s already precedent for this: As he left office in 2003, Illinois Governor George Ryan shuttered the state’s 167-person death row in one fell swoop. The governor best positioned to deliver such a blow today is Jerry Brown. More than 700 prisoners are on death row in California, by far the nation’s largest, even though the state hasn’t executed anyone since 2006. But Brown’s clemency spree has left the state’s death row at San Quentin State Prison largely untouched. While he has shown pardons to be a powerful tool for criminal justice reformers, he has left plenty of work for his successor to do.

On Tuesday, two days after Elizabeth Warren announced her candidacy for president, an aide gave a statement to Axios that suggested the Massachusetts senator intends to court the green-leftist vote: “Senator Warren has been a longtime advocate of aggressively addressing climate change and shifting toward renewables, and supports the idea of a Green New Deal to ambitiously tackle our climate crisis, economic inequality, and racial injustice.”

But for some environmentalists, this rather anodyne statement was cause for concern, not celebration: She only supports the idea of a Green New Deal?

Those words are a worrying caveat, said RL Miller, political director of the super PAC Climate Hawks Vote, who noted that Warren hasn’t signed the Green New Deal’s pledge not to accept campaign donations from fossil fuel companies. “This will be our litmus test,” Miller said. “You don’t sign on to this, we don’t support you, period, full stop.”

Miller isn’t alone in her skepticism. Jack Clarke, the policy director at Mass Audubon, recently told E&E News that Warren “does not have a record of advocacy and leadership on climate change issues.” The news outlet surveyed the climate community about Warren’s record, and activists “struggled to name a climate issue on which the senator has made a name for herself.”

Make no mistake: Warren has a strong environmental record. She has near-perfect lifetime score from the League of Conservation Voters, and last year introduced a bill that would require public companies to disclose climate-related business risks. The fact that climate activists are hesitant to embrace the top progressives of the 2020 field shows how much the politics of climate change have shifted since 2016. The green vote matters more than ever—and it will be harder than ever to win it.

It’s no longer enough to repeatedly declare that global warming is real, or even to make the issue central to your campaign, as senators Bernie Sanders and Jeff Merkley reportedly will do if they run for president. Even declaring that climate change is your top priority might not be enough. Earlier this week, when he effectively announced his candidacy in an interview with The Atlantic, Washington Governor Jay Inslee made clear what his top priority would be: He called climate change “the defining challenge of our time,” adding that there’s a “need for a presidential candidate who will put fighting climate change front and center. This is our legacy.”

For millions of Americans, climate change is no longer just a graph or a chart. It's floodwater invading their homes. It's ash on their tongues from raging wildfires. From Washington State to Texas to Puerto Rico, we are living climate change right now.

— Jay Inslee (@JayInslee) January 2, 2019Inslee is already being called the “climate candidate,” and perhaps rightly so. Unlike potential candidates such as senators Bernie Sanders, Cory Booker, and Kamala Harris, “Inslee is the only one who has actually run a government that has made climate-change policy central,” The Atlantic noted:

He was elected governor in 2012 and has, without much national notice, pursued arguably the most progressive and greenest agenda in the country, with fields of solar panels, fleets of electric buses, and massive job growth to show for it. And years before anyone was tweeting about the “Green New Deal,” Inslee wrote a climate-change book while he was in Congress: Apollo’s Fire, a 2007 blueprint for how much economic and entrepreneurial opportunity there is in saving the planet.

And yet, even Inslee is not immune to criticism from the environmental left. “Where’s the racial justice component in his overall climate approach?” asked Anthony Rogers-Wright, the deputy director of RegeNErate Nebraska. Miller is concerned that Inslee might approve a $2 billion methanol refinery in Washington, a controversial project which green groups say would “fuel the climate catastrophe [Inslee] is supposed to help curb, not escalate.”

These are the sorts of questions that climate activists are itching to ask in the upcoming primary season—and they may finally have the leverage to demand specific, unconditional answers.

At lot has changed since the 2016 election, when global warming barely featured in the televised debates. Last year brought record-breaking extreme weather that caused billions of dollars worth of damage across the country and world, and scientists sounded more alarmed than ever. The most frightening report, released by the United Nations in October, said the world only has about a decade to rein in emissions before irreversible catastrophic impacts begin.

Meanwhile, President Trump is withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris climate accord and is in the process of rolling back nearly a dozen climate regulations. A report in The New York Times this week showed how these moves present an opportunity for Democrats. An Indiana county that voted overwhelmingly for Trump has seen a rash of childhood cancer, and recent tests at an old industrial site revealed “a carcinogenic plume spreading underground, releasing vapors into homes.” The specific chemical—trichloroethylene, or TCE—is one for which Trump wants to weaken restrictions.

The increasingly dire news about global warming, and Trump’s furious assault on climate regulations, have turned the issue into one of the top priorities among Democratic voters. As the party’s base shifts left, it’s demanding more aggressive positions from politicians—and applying more aggressive tactics against politicians who don’t. Nearly 150 activists were arrested in one of two protests the Sunrise Movement held at the U.S. Capitol late last year, where they demand that Democrat leaders like Nancy Pelosi explicitly support the specifics of a Green New Deal.

“In 2020, people are going to be actually listening intently to what Democrats have to say about climate change,” Rogers-Wright said. “And there are gonna be some people running who have some explaining to do.” Stephen O’Hanlon, Sunrise’s communications director, said the group is “focused on pushing all the candidates to back the Green New Deal and reject fossil fuel money, which is the minimum they need to do in order to be taken seriously by our generation.”

The 2020 candidates are all vulnerable in one way or another. Warren is far from the only potential Democratic presidential candidate who hasn’t signed the pledge; Booker, Harris, Inslee, and O’Rourke haven’t as well. In O’Rourke’s case, he had signed the pledge while running his unsuccessful Senate campaign against Ted Cruz, but was removed after it was revealed that he accepted $430,000 from oil and gas industry employees. That’s a potential deal-breaker for some. “Solving climate change requires essentially dismantling the fossil fuel industry,” Rogers-Wright said. “How can we expect you’re going to dismantle a group that’s investing in you?”

But being the leftmost Democrat on climate change is no guarantee of support, either. Merkley has signed the no-fossil-fuels pledge, and has been a leader in introducing climate legislation in the Senate, but Rogers-Wright questioned his effectiveness. “You have to do so much more than have the policy to solve the climate crisis,” he said. “It will require a lawmaker who is skilled at bringing people together and holding people together, and I don’t know that Merkley has those chops.”

So who is leading the pack, as far as climate activists are concerned?

“I’m not sure anyone is really excited [about the 2020 field] yet,” said Miller of Climate Hawks Vote. O’Hanlon said that Sunrise has met with staffers from a number of potential candidates, “and right now don’t have a favorite.”

That’s not surprising, given the early stage of the race. The question is whether any candidate will do enough to satisfy some activists. As Rogers-Wright noted, the Democratic Party has not developed a plan to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. “Sure, they believe in [climate change],” Rogers-Wright said. “But as it pertains to acting on it, they’ve been anemic at best.”

In fact, none of the potential Democratic candidates—aside from Sanders, who ran in 2016—has released such a plan, either. But there is time yet for that, and pressure from environmentalists may well compel them to do so. As Miller said, “This is finally going to be the climate election that we’ve been waiting for.”

The black-and-white video looks, just for a moment, like it might be a real cooking show. The female host holds up a chalkboard displaying its title, then puts on her apron and picks up a bowl. Yet instead of preparing food, she begins to stir with an invisible spoon. One by one, she picks up kitchen utensils and says their names aloud, making her way through the alphabet—“apron,” “bowl,” “chopper,” “dish,” and so on—until she reaches U and starts spelling out the rest of the letters with her body. She never handles any food.

Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen is one of the artist’s most beloved works. The six-minute video parodies cooking demonstrations, replacing the typical gracious host with, in the artist’s words, “an anti-Julia Child” played by Rosler, who doesn’t smile and maintains a withering stare throughout. The performance is both funny—Rosler delivers the whole thing deadpan, breaking character only slightly at the end to shrug—and full of rage. Rosler uses a familiar form to critique the oppression of women through domesticity, and to subvert the kinds of knowledge and behavior this requires. She swallows her anger long enough to get through the whole alphabet, but the tension is palpable. It hangs in the air—which she slices with a knife as she outlines the letter Z.

Rosler made Semiotics of the Kitchen in 1975, a year after receiving her MFA from the University of California, San Diego. At the time, Southern California was home to a robust feminist art scene: Judy Chicago had established the first feminist art program in the country at Fresno State a few years earlier, and the landmark exhibition Womanhouse took place inside a rundown mansion in Hollywood in 1972. Female creators were embracing and experimenting with the relatively new forms of performance and video, leaving behind the modernist and sexist baggage of painting. Rosler had moved to California from New York City as what she calls “a semi-lapsed painter but also a maker of photographs, photomontages, and a bit of sculpture,” but it wasn’t long before she was performing and recording herself.

Much of Rosler’s art over the course of her more than 50-year career has been concerned with the treatment of women, yet she has gone on to treat other subjects in equal measure. The look and focus of her work have changed often, from video taking apart the media’s endorsement of torture, to photographs of her gentrifying Brooklyn neighborhood, to head-on critiques of President Trump. She’s never developed a “signature style,” as Holland Cotter noted in a 2000 review. This is likely the reason that some critics have found it difficult to clearly define her project. She has not been pigeonholed as a “feminist artist” in the same way that Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, and Carolee Schneemann have. She’s often called a “political artist,” or, less approvingly, a maker of simplistic “activist art,” but these catchall terms are more vague than they are useful.

A new survey of Rosler’s work at the Jewish Museum, titled Irrespective, helps bring into focus the contours of her politics, as it illuminates her urgent curiosity about the workings of society. Gathering samples of a seemingly disparate oeuvre, the exhibition shows Rosler returning to and reexamining the same issues: gender roles, economic class, globalization. Crucially, Irrespective demonstrates how Rosler has adopted feminism not simply as a subject, but as an intellectual and artistic framework. “Feminism is a viewpoint,” she has written, “that demands a rethinking of all structural relations in society.” She has made that rethinking her life’s work, exposing hidden assumptions and attempting to shift our gaze toward the systems we might take for granted. She wants us to see more clearly how the world operates, so that we’ll be better equipped to change it.

It’s rare that an artist starts out making some of their strongest and most enduring work, but that is the case with Rosler; she seems to have emerged with her priorities and talent fully intact. The exhibition acknowledges this by opening with a blown-up, wallpaper version of “Cargo Cult,” a work from Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain (c. 1966–72), a photomontage series Rosler started before she moved to California. “Cargo Cult” features magazine pictures of women applying makeup, pasted onto stacked shipping containers in a port. Several men are at work, lifting the containers by crane in order to get them where they need to go. The piece calls out the impossible beauty standards that society imposes upon women, but there’s more going on. The women applying makeup are all white, and the men moving the boxes are black. “Cargo Cult” reminds us that the apex of beauty in the United States is whiteness—a dangerous idea that we are exporting to other countries.

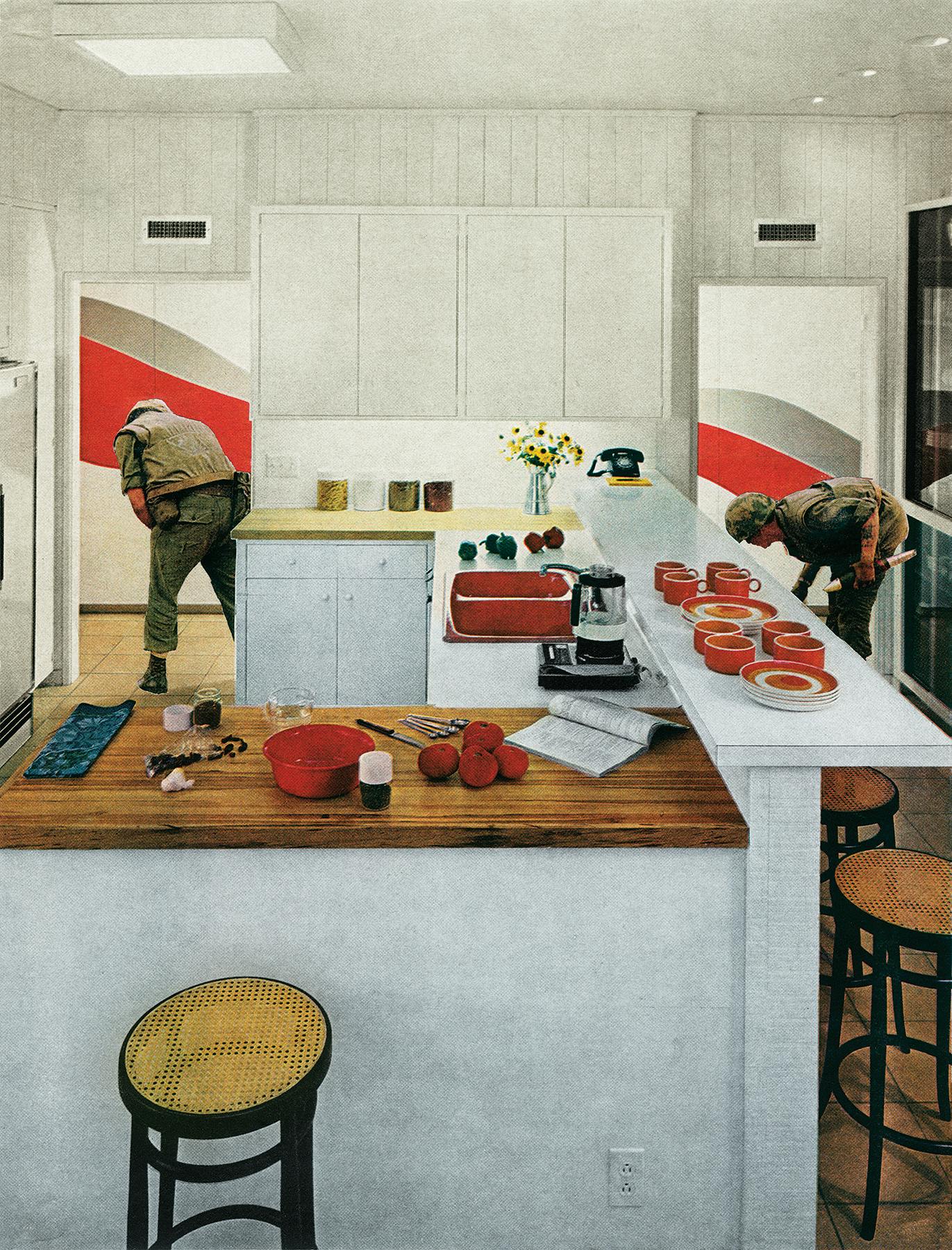

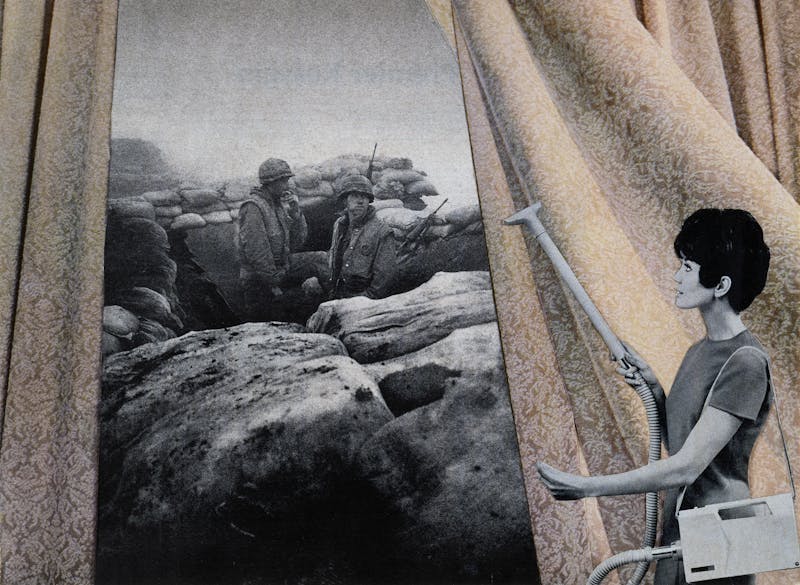

The combination of different pictures is so seamless that it’s jarring. Although you can tell almost immediately that the image must be doctored, it beguilingly retains its formal integrity. Rosler does the same thing to powerful effect in what’s probably her most famous series, House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (c. 1967–72). Originally made as flyers that she distributed at Vietnam War protests, the works in House Beautiful combine imagery of the “living room war”—the first conflict that Americans saw unfold on their televisions at home—from Life and other media sources with photographs and advertisements mostly from House Beautiful, an interior-decorating magazine.

One of the images, “Red Stripe Kitchen,” shows two soldiers appearing to search for explosives in a gleaming white modern kitchen; their presence is somehow incongruous and innocuous at the same time. Another, “First Lady (Pat Nixon),” portrays the president’s wife in a stately gold room, where the painting above her head has been replaced by a photograph of a dying woman; her closed eyes and pained expression make for a stark contrast with Nixon’s cheerful smile. In 2003, ’04, and ’08, Rosler made a new set of House Beautiful works in response to America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; rather than feeling like a retread of old material, they’re filled with freshly horrific juxtapositions. In “Photo-Op” (2004), the faux-shocked faces of two blonde models posing with cell phones look especially callous in the presence of two injured or dead children in sleek chairs behind them, while an explosion lights up the sky outside.

House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home captures, at a very early point in her career, the nature of Rosler’s feminism—it was a wide-angle lens, a way of looking out at the rest of the world, as well as an impetus to examine the experiences of women. In contrast to many in the movement around her, Rosler has never seemed especially interested in the plight of middle- and upper-class white women. She instead uses familiar images of them as lures: “Like a wooden decoy duck,” the glossy magazine images draw the eye in, she has explained, but then, “on closer inspection these things turn out to be something other.” The works aim to expose the scaffolding on which normalcy itself is built: The tastefully appointed interiors at home rely on the imperialistic wars abroad more than we might care to admit.

“Cleaning the Drapes,” also from House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home.Courtesy of Martha Rosler/Mitchell-Innes & Nash/The Jewish Museum, New York.

“Cleaning the Drapes,” also from House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home.Courtesy of Martha Rosler/Mitchell-Innes & Nash/The Jewish Museum, New York.In Body Beautiful and House Beautiful, Rosler is a trenchant media critic. For her, the question of what we know (or think we know) is inextricably bound up with how we’ve learned it. But there’s a limit to the complexity that can be conveyed in photomontages, a form that ultimately relies on many of the same visual principles as the media that it critiques. What happens after you’ve caught the viewer’s eye?

In Rosler’s video A Simple Case for Torture, or How to Sleep at Night (1983), she took a different approach. The work is a response to a Newsweek essay that argued torture is sometimes “morally mandatory.” Over the course of an hour, we see disembodied hands paging through newspaper articles and magazines; they’re punctuated by typewritten key phrases (“lives of the innocents”) and accompanied by jagged bursts of music and voices detailing stories of torture in Latin America. The video is dense, self-reflexive, and makes little appeal to viewers’ emotions. It seems designed to overwhelm us with a barrage of information and push us toward a state of enlightened alienation.

This rigorous, almost dissertation-like approach is another hallmark of Rosler’s practice. But Irrespective also highlights a less familiar and more straightforward method she has used to reach audiences. Her photography series directly present Rosler’s own point of view, in a departure from her use of found images. One gallery groups Ventures Underground (c. 1980–ongoing), In the Place of the Public: Airport Series (1983–ongoing), Rights of Passage (1993–98), and Greenpoint Project (2011). These are intimate pictures shot while riding subways around the world; photographs of gleaming airport interiors; panoramic images of lifeless highways and bridges taken while driving; and pictures and short passages about local businesses in her neighborhood. Many of these works feel diaristic, like private glimpses into the life of an artist who has tended to look outward, rather than in on herself. There are no added layers of mediation, with the exception of the evocative words and phrases (“trace odors of stress and hustle”) that fill the gallery wall to complete In the Place of the Public.

All of this may be why the photographs feel more like process notes than finished products. Yet the series—especially the three about travel—are consistent, in their own way, with Rosler’s project. She interrupts the flow of everyday life to reframe it with a critical eye—to make us pause and consider the spaces we pass through routinely. Staring at stone-faced passengers boxed into metal subway cars and at concrete stretches of highway, she prompts the viewer to think about the harshness of the built environment. When such alienating spaces connect our cities, is it any wonder that many of us struggle to link ourselves personally and politically to others?

Irrespective is an excellent introduction to Rosler’s oeuvre, establishing some of her core concerns. Its weakness is that it’s a relatively small, object-focused show, whereas some of her most exciting and instructive art has been collaborative, public, and even ephemeral. Perhaps most notably, there are the garage sales she held between 1973 and 2012. In each case, she arranged a hodgepodge of secondhand items—underwear, chairs, animal figurines, even bad paintings—and offered them to the public at arbitrary prices. Part-installation, part-performance, the sales commented cleverly on the complicated ways we determine value, bringing items typically thought of as disposable or cheap into art spaces, where objects are expensive and reign supreme.

Rosler has also made powerful interactive work about housing. In 1989, she organized a landmark series of three exhibitions at the Dia Art Foundation under the title If You Lived Here… Each focused on a different aspect of the housing crisis in New York City, and all included work not only from artists but also from community groups and homeless people. She also held four town hall meetings. The project ignored established hierarchies, as Rosler brought art and artists into dialogue with the wider community, in part to point out their role in the process of displacement: Artists moving into a neighborhood often heralds the beginning of rent increases that squeeze current residents. At the same time, she gave the community access to the resources of the art world.

It’s disappointing that these and Rosler’s other socially engaged works are not represented in the galleries at the Jewish Museum, only in the Irrespective catalog. These projects are the most radical manifestation of her approach to political art making. They shift the relationship of artist to audience so that it’s less top-down: Rather than making a video to tell viewers everything she thinks they should know about the housing crisis in New York City, she creates a space where they can go, learn, and ask questions. Rosler becomes an informed facilitator rather than the sole authority.

After all, if the final gallery at the Jewish Museum urges anything, it’s not to trust those with grand claims to authority. The room features two works about President Donald Trump: a digitally distorted compilation of footage from the White House and a print of Trump, overlaid with two sets of text—a comment he made about being able to shoot someone and not lose voters, and the names of people of color who have been killed by the police. The Trump works are the weakest in the show; Rosler hasn’t figured out how to tell us something we don’t know yet. But they share space with two other projects, both about books, and this sets up a clear conceptual battle between the pursuit of truth and a disregard for it.

One of those is Off the Shelf (2008, 2018), a series of digital photomontages of books from Rosler’s library. The volumes are grouped thematically under such titles as “Utopian Science Fiction, F” or “War and Empire” and seem to float within gradient-colored spaces, untethered from any physical reality. The series represents an ideal of the pure transmission of knowledge—one that Rosler attempted to manifest between 2005 and 2009 by actually turning her library into a traveling installation that viewers could browse.

The other is Reading Hannah Arendt (Politically, for an Artist in the 21st Century) (2006), which occupies the center of the gallery. Fourteen clear mylar panels hang from the ceiling, each one containing a passage, in German and in English translation, from the political philosopher’s 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism. The work is simple but effective: The panels are hung at odd angles so that viewers may walk between them, immersing themselves in words that feel weighted with moral and emotional clarity. “Intellectual, spiritual, and artistic initiative is as dangerous to totalitarianism as the gangster initiative of the mob, and both are more dangerous than mere political opposition,” it reads, and here we are, face to face with that reality. The work points us back to what Rosler has been telling us all along: Look again, closely, at what you think you know, and don’t doubt the importance of what you find.

No comments :

Post a Comment