BuzzFeed set off a cascading series of controversies last week when it reported that President Donald Trump had “directed” his longtime personal attorney Michael Cohen to lie to Congress about a Trump Tower deal in Moscow that was being negotiated during the 2016 election. The immediate takeaway was that, if the report were true, then Trump had committed a straightforwardly impeachable offense. The allegation was “so cut-and-dried that even Republicans would be hard-pressed not to consider impeachment,” wrote Aaron Blake in The Washington Post. Democrats in Congress raised the alarm. “If the President directed Cohen to lie to Congress, that is obstruction of justice. Period. Full stop,” Rhode Island’s David Cicilline, a member of the House Judiciary Committee, tweeted.

But then, as happens so often in this presidency, the story quickly became clouded by uncertainty and accusations of media bias. The office of the special counsel issued its first public response to a specific story since Robert Mueller began investigating Russia’s involvement in the election. “BuzzFeed’s description of specific statements to the Special Counsel’s Office, and characterization of documents and testimony obtained by this office, regarding Michael Cohen’s Congressional testimony are not accurate,” the statement read. You could practically hear the sighs of relief in the Oval Office. Trump even went so far as to express gratitude to Mueller, his most implacable enemy: “I appreciate the special counsel coming out with a statement last night,” he said. “I think it was very appropriate that they did so, I very much appreciate that.”

But there’s no reason to doubt that Trump has, in fact, repeatedly instructed subordinates to tell lies to Congress and law enforcement authorities, including lies that amount to crimes. The difference is that the media outlets that reported those other cases didn’t say, explicitly, that the president “directed” his aides to lie. Another important difference is the way in which Trump gets his subordinates to lie, which has served to delay the moment when we all admit that he is quite clearly suborning perjury.

BuzzFeed, which sourced its claims to “two federal law enforcement officials involved in an investigation of the matter,” claimed that this was “the first known example of Trump explicitly telling a subordinate to lie directly about his own dealings with Russia.”

It wasn’t.

In September 2017, The New York Times revealed that over a weekend at Bedminster Golf Club with Trump, White House aide Stephen Miller drafted a memo explaining why the president was firing former FBI Director James Comey—the event that immediately precipitated the launch of the special counsel’s investigation. The letter cited comments Comey had made about the FBI’s investigation into Russia’s interference in the 2016 election. White House counsel Don McGahn later massaged those references in Comey’s actual termination letter, to suggest that Comey was being fired for a different reason (though Trump would admit that the Russia investigation was the actual cause days later on television). Given that McGahn’s letter was sent to the FBI director, it amounted to a lie to the bureau.

The president’s subordinates and son lied to authorities, including Congress and the FBI, with his tacit knowledge and even scripting.Then last June, the Times published a January 2018 letter in which Trump’s lawyers admitted to Mueller’s office that “the President dictated a short but accurate response to the New York Times article on behalf of his son, Donald Trump, Jr.” The letter tied that statement directly to Don Jr.’s testimony to Congress about the infamous Trump Tower meeting in 2016, in which Don Jr. sought to procure damaging information about Hillary Clinton from Russian agents. “His son then followed up by making a full public disclosure regarding the meeting, including his public testimony that there was nothing to the meeting and certainly no evidence of collusion.” Trump’s statement to the Times claimed there had been “no follow-up” after the June 9 meeting, and Don Jr.’s testimony to Congress sustained that claim. But the public record shows there was follow-up after the election.

Both of these instances (and other less clear-cut examples) show how Trump has gotten aides to provide false statements to investigating authorities and Congress. It’s just that the Times didn’t state what was clear: The president’s subordinates and son lied to authorities, including Congress and the FBI, with his tacit knowledge and even scripting.

BuzzFeed, however, was not so squeamish about identifying what—it continues to insist—its evidence showed.

The response was explosive. Democrats like Representative Ted Lieu of California suggested impeachment proceedings could arise from Trump’s apparent obstruction of justice. Even House Judiciary Chair Jerry Nadler, who has cautioned against a rush to impeachment, asserted, “We know that the President has engaged in a long pattern of obstruction,” before promising, “The @HouseJudiciary Committee’s job is to get to the bottom of it, and we will do that work.” (The House Judiciary Committee would oversee any impeachment inquiry.)

The alarm wasn’t limited to Democrats. White House spokesperson Hogan Gidley, after claiming to Fox News that media outlets were “just using innuendo and shady sources,” still did not deny the story. Fox’s Chris Wallace, while warning to take the BuzzFeed story “with a giant grain of salt,” admitted, “It’s the kind of thing that can get you impeached.”

It didn’t help that William Barr, Trump’s nominee to be attorney general, agreed twice in his confirmation hearing last week that if a president encouraged someone to testify falsely it would amount to obstruction of justice. Barr agreed that a president—or any person—who persuades a person to commit perjury or change testimony would be committing obstruction. Barr also concurred when Senator Lindsey Graham asked, “If there was some reason to believe that the president tried to coach somebody not to testify or to testify falsely, that could be obstruction of justice.”

The president’s lawyers were apparently so anxious that, according to multiple news outlets, they “raised concerns” in a letter to Mueller’s office. And according to The Washington Post, the office of Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein called Mueller’s office to find out if he would be releasing a statement.

When the statement from Mueller’s office finally dropped, the discussion of impeachment, which had rapidly grown rampant, was curbed. But what we know so far indicates that Trump, in at least one previously known case involving Don Jr., scripted someone to lie under oath, which means that all the concerns voiced by Democrats and Fox News anchors in response to the BuzzFeed story remain as valid as ever. It’s the kind of thing that can get you impeached.

Furthermore, the special counsel’s statement did not exonerate the president, rare as it might be for his office to rebuke the press. The statement merely distinguished what that office had obtained in its investigation from what BuzzFeed said the office had obtained. That’s significant because, in Cohen’s case, Mueller’s prosecutors are working with another Justice Department office, the Southern District of New York, on parallel prosecutions. Indeed, FBI agents working with SDNY conducted the raid on Michael Cohen’s home in April, gathering information that was then shared with Mueller’s people.

Indeed, there are notable differences in the way the two prosecutions characterize the degree to which Trump—referred to as Individual-1 or Client-1 rather than by name—directed Cohen’s illegal conduct. With respect to hush payments to Stormy Daniels and Karen McDougal, Cohen admitted in the SDNY case that he acted “on Client-1’s instruction, to attempt to prevent [women alleging to be the Candidate’s former sex partners] from disseminating narratives that would adversely affect [his] Campaign.” By contrast, in Mueller’s case, Cohen claimed that, when he lied to Congress about the Trump Tower deal in Moscow, he was “seeking to stay in line with” the message Trump and “White House-based staff and legal counsel to Trump” were pushing regarding Trump’s ties to Russia.

That is, in pleading guilty to SDNY prosecutors, Cohen said Trump “instructed” him to take action. But in pleading guilty to Mueller’s prosecutors, Cohen said he was following the messaging of Trump’s advisers, without claiming to have been instructed to do so. In both cases, however, Cohen said loyalty to Trump led him to commit crimes to sustain Trump’s desired message.

This dynamic may be why it has been so hard for other news outlets to do what BuzzFeed did: to state that Trump induces his aides to lie, not just as a routine matter, but also in ways that break the law. Trump gets those around him to lie in a different manner than past presidents.

Under Trump, the lies are facilitated not through any kind of bureaucratic genius, but instead through an insistence that underlings toe the public line.Consider how some of George W. Bush’s most disastrous lies worked. With both the claim that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and that the CIA was just vigorously interrogating detainees rather than torturing them, Bush’s top aides either ensured he retained plausible deniability to the lies or his public claims were technically correct. It was technically true that, “The British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.” Left unsaid was that the U.S. government had already judged that Saddam didn’t actually obtain the uranium he sought.

With Bush’s lies, the buck often stopped with Vice President Dick Cheney. And Cheney exploited his bureaucratic genius, both inside and outside government, to ensure message discipline. One reason Cheney started collecting information on Valerie Plame and her husband Joe Wilson’s trip to Niger, in an effort that would lead to the disclosure of her CIA status, was because CIA analysts close to Plame were leaking details of what the CIA had really known to the press. Similarly, people close to Cheney had a hand in the consistent use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” in the most secret realms of government, in memos rubber-stamping the torture, and on the front page of The New York Times.

There is no such plausible deniability in the Trump administration. Under Trump, the lies are facilitated not through any kind of bureaucratic genius, but instead through an insistence that underlings toe the public line. These lies include more innocuous ones like inauguration attendance, as well as more serious ones involving Trump’s awareness that a Russian linked to military intelligence was brokering a $300 million real estate deal at the same time that Russia’s military intelligence was offering dirt stolen from Trump opponent’s server to his son.

In fact, that’s the theory presented in all three of Mueller’s cases in which a Trump aide lied about matters pertaining directly to Russia’s involvement in the campaign. Under oath, Cohen explained that he lied about the Trump Tower deal “to be consistent with Individual 1’s political messaging and out of loyalty to Individual 1.”

In his sentencing memo, George Papadopoulos said his lies about Russians offering the campaign Hillary Clinton’s emails were not meant to impede the investigation but “to save his professional aspirations and preserve a perhaps misguided loyalty to his master.” By his own account, Papadopoulos lied “out of loyalty to the new president and his desire to be part of the administration.”

And in explaining why former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn told lies—which included false statements to the FBI about his communications with the Russian ambassador to the U.S.—the government said, “By the time of the FBI interview,” Flynn “was committed to his false story.” We know that Flynn took those actions, in part, to avoid a “tit-for-tat escalation” that would make it difficult to improve relations with the Russians after they had just “thrown [the] USA election” to Trump, according to Flynn’s deputy K.T. McFarland.

Mueller has hinted that Trump’s other subordinates were involved in just one of these lies: Cohen’s. In a filing describing how Cohen explained “the circumstances of preparing and circulating his response to the congressional inquiries,” Cohen suggested he coordinated with “White House-based staff and legal counsel to Trump.”

That’s what the public record shows happened with Cohen’s statements about the Trump Tower meeting, in which he falsely claimed there was no “follow-up.” Trump dictated that line himself in July of 2017, and his camp has never deviated from it.* Trump Organization lawyers urged Rob Goldstone, who set up the meeting, to endorse the claim. They did this even though they had to have known it wasn’t true. Indeed, less than a week after Trump’s lawyers tried to get Goldstone to back him up, Trump’s assistant forwarded Goldstone an email he sent her the prior year, showing it to be false.

So where do all the lies come from? The record indicates that Trump decides what lie is going to be told, and the people around him, indirectly or otherwise, do what they need to sustain it, even if it includes lying to Congress, the FBI, and Mueller’s team.

Legally, the difference between ordering someone to lie and simply ensuring they follow your message out of abject loyalty may not save Trump. There is one law, subornation of perjury, that imposes up to five years in prison if a person “procures another to commit any perjury.” Even aside from whether Trump personally directed his aides to tell lies, the crime Trump’s aides, including Cohen, have been prosecuted for thus far has been false statements, not perjury. A more basic law makes it a crime to “aid, abet, counsel, command, induce, or procure” an offense against the United States, in which case that person can be charged “as a principal.” In past presidential cover-ups, conspiracy to obstruct justice was charged. So Trump could be on the hook for the lies he encouraged his subordinates to tell, too, sometimes with the help of his lawyers.

In this administration, the president doesn’t need to order his subordinates to lie for him. It’s a daily matter of course. Mueller’s team seems to be wise to that, even if Congress and much of the media aren’t quite there yet.

*A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Donald Trump asserted to his team in 2016 that there was no follow-up to the Trump Tower meeting. He made the assertion in 2017. We regret the error.

Just a few months ago, it seemed like Nancy Pelosi’s bid to become speaker of the House of Representatives was in trouble. While attacks from the right had been commonplace for years, she came under fire from members of her own party, many of who wanted the Democrats to promote a new generation of leaders. Democrats running for their first term in the House from across the political spectrum—Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on the left, Conor Lamb on the right—kept their distance, while even some incumbents declared that it was time for a change. After Democrats’ landslide victory, CBS News declared Pelosi had a “math problem” because 16 members of her caucus had signed a letter opposing her as speaker.

It all came to nothing. Pelosi swiftly undercut the rebellion, which failed to coalesce around a single challenger, and was easily reelected earlier this month. Now the party’s de facto leader until its 2020 convention, she’s already proving her detractors wrong by dominating President Trump—both on camera and behind the scenes—as only a seasoned, ruthless legislative leader could do. She’s also managed to keep her Democratic colleagues in line, from her more squeamish and less calculating counterpart in the Senate, Chuck Schumer, to the young insurgents who sought her ouster.

Ever since Republicans partially shut down the government over Trump’s demand for border wall funding, Pelosi has followed a simple and effective strategy: Don’t budge an inch. The president is unpopular, the shutdown is unpopular, and a sizable majority blames the former for the latter. Thus, as The Atlantic’s Peter Beinart noted recently, “Republican members of Congress are under more political pressure to back down than their Democratic counterparts, and the longer the shutdown continues, the more that pressure should grow.”

Pelosi knows that she can win this standoff if she holds her caucus together and doesn’t compromise. In accomplishing both thus far, she’s laying waste to Trump’s presidency, preventing him from fulfilling his key campaign promise—the construction of a massive border wall—and pushing him to new lows of unpopularity, while her own poll numbers soar. If she keeps it up, the past month may go down as Pelosi’s greatest political accomplishment—and even redefine her place in American history.

The campaign against Pelosi began in earnest last spring when Lamb, running in a special election for a conservative seat in western Pennsylvania, pledged not to vote for her as speaker. To the surprise of many, he won. Over the ensuing months, dozens of Democrats then distanced themselves from Pelosi on the campaign trail, with many pledging to oppose her return to the speakership.

Congressional leaders rarely poll well. They’re always unpopular with supporters of the rival party, of course, but also with many members in their own party (usually those who want a more radical agenda) and independent voters (who blame the leaders for Congress’s dysfunction). Pelosi, however, has been especially unpopular with the American public, owing to several factors: her gender; her long reign of power; and conservatives’ effective depiction of her as the epitome of the tax-and-spend San Francisco liberal.

But there have been salient criticisms of Pelosi, too. Some Democrats were concerned that she and senior House leadership had not done enough to cultivate new leaders within their ranks. “The notion that there’s no one more experienced than Nancy Pelosi is a self-fulfilling prophecy because you can’t have experience if you can’t gain experience,” one senior Democratic aide told The Atlantic’s Elaina Plott. “Our best members will keep leaving when they continue to see there’s no movement at the top.” When the rebellion against Pelosi fully materialized after the midterms, it rallied around a simple message: She’s too old. It’s time for new blood.

This argument was not particularly persuasive, as I argued at the time, because it was largely being pushed by Democrats from the party’s right wing, like Massachusetts’ Seth Moulton, who were under pressure from voters (and, in some cases, donors) to oppose the San Franciscan. More fatally, the rebellion had its own math problem: It had not rallied around a single leader to challenge Pelosi. So she swiftly won over her caucus, and many of its new progressive incumbents, by offering committee posts and compromises, like a “leadership development” and a pledge to step down in 2022—when she planned on retiring anyway.

Pelosi proved her mettle even before the government shutdown began. During an Oval Office meeting in December with Trump, who had unexpectedly invited TV cameras in an apparent ambush, she and Schumer bamboozled him into taking credit for the looming shutdown. “I will take the mantle,” he said. “I’m not going to blame you for it. The last time you shut it down, it didn’t work. I will take the mantle of shutting down, and I’m going to shut it down for border security.” The press has not allowed Trump to forget that admission, even as he has tried to blame Democrats for the shutdown.

Since the shutdown began 33 days ago, Pelosi has repeatedly stood up to Trump. She has brushed aside his proposals to reopen the government as “nonstarters” because of his insistence on $5.7 billion for the border wall, which she calls “an immorality.” She has pressured him to postpone the State of the Union, scheduled for next Tuesday, over shutdown-related security concerns, which may force him to hold the event elsewhere. She has also largely kept Schumer, who has been criticized by many Democrats for his willingness to work with Republicans, in lockstep. Pelosi had deferred to Schumer during Trump’s first two years in office, but a top Democrat told Politico “the dynamic is changing.”

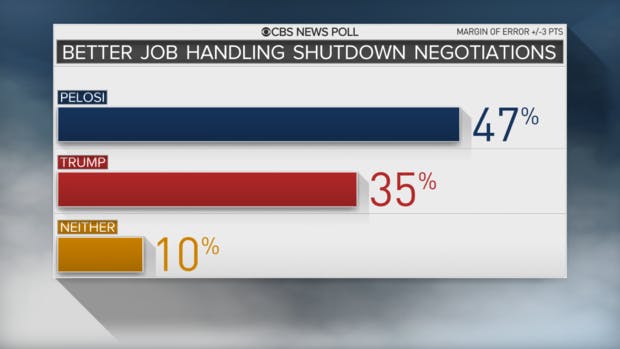

Americans like what they’re seeing from her. New polling shows that Pelosi’s popularity has jumped. According to polling from Civiqs, Pelosi’s favorability has jumped 13 points among Democrats, from 59 to 72 percent. “It appears, then, that Pelosi’s opposition to the president has rallied her party’s base and increased her favorability ratings,” argued The Washington Post’s Michael Tesler. But it’s not just Democrats who approve of her performance during the shutdown. As a CBS News poll released on Wednesday found, “Among Americans overall, and including independents, more want to see Mr. Trump give up wall funding than prefer the congressional Democrats agree to wall funding. Comparably more Americans feel House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is handling negotiations better than the president is so far.”

Democrats are winning the shutdown thus far because they haven’t compromised—and they have no reason to do so, given the unpopularity of the president and the border wall. The length and severity of this shutdown, now the longest in U.S. history, could do lasting damage to Trump’s presidency. If so, we may be witnessing the pinnacle of Pelosi’s career. She had already proven herself as a resolute obstructionist when she thwarted George W. Bush’s plan to privatize Social Security in 2005. In 2009 and 2010, she proved herself a master legislator when she passed Obamacare, which she helped resuscitate, and the (ultimately doomed) cap-and-trade bill. But given the stakes of the current political moment, the character of the president, and the criticism she has fielded over the past year, her recent performance against Trump will change the story that’s told about her in history books.

Looking ahead to 2020, progressives may yet have reason to be skeptical about Pelosi’s continued hold on the gavel—especially if Democrats win back both the presidency and the Senate. She has, especially recently, shown herself to be cautious when confronting the progressive wing’s increasingly ambitious agenda. She implemented a pay-go rule in the House, requiring new spending to be offset by budget cuts or tax increases. On Medicare for All, she has largely advocated for strengthening Obamacare, but did recently allow hearings on universal health care to go forward. As for Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal, Pelosi does not seem to be a fan: Earlier this year, she rebuffed the freshman’s attempt to form a committee on the proposal. Finally, while she has advocated for younger leaders, she has tended to privilege corporate-friendly centrists like Hakeem Jeffries over progressives like Barbara Lee.

But 2020 is a long way off, and Democrats’ unified control of the government may be an even longer way off. For now, by undercutting and emasculating Trump at every turn, Pelosi is determined to turn the shutdown into the beginning of the end of his presidency. In doing so, she has earned the loyalty of her entire caucus. Winning tends to have that effect.

Jill Abramson’s new book, Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts, is billed as a “definitive report on the disruption of the news media over the last decade,” even as Abramson concedes halfway through that “[a]ny narrative, even one that is scrupulously factual and deserving of the omniscient third-person voice of the journalist-historian, is subjective by nature.” The common ground between “subjective” and “definitive” is a small place, but Abramson, as the first woman executive editor of The New York Times, is well placed to claim it. Her tenure at the top of the Times, from 2011 to 2014, coincided with the great shift in news publishing from print to digital, with all the financial chaos and ethical quarrels over clickbait that followed. The book is also a bitter account of the end of Abramson’s career at the Times, placing her own story in the middle of an ongoing debate over diversity in the newsroom.

MERCHANTS OF TRUTH by Jill AbramsonSimon & Schuster, 544 pp., $30.00

MERCHANTS OF TRUTH by Jill AbramsonSimon & Schuster, 544 pp., $30.00Abramson’s experience at the pinnacle of American journalism could make her the best person to tell this story, since she had such a good view. It could also make her the worst, since she has a personal stake in trashing certain people and organizations. In Merchants of Truth, she ends up being a little of both. To write the history of the news industry in the twenty-first century, Abramson juxtaposes the troubles of the Times and The Washington Post with the rise of Vice Media and BuzzFeed. It is very clear where Abramson’s heart lies, and the heart tends to lead one’s head. The chapters on the Times and the Post are excellent. The other chapters are not.

In recent weeks, several younger journalists cited in Merchants of Truth have sparked a huge backlash to the book on social media, claiming that Abramson has misreported everything from their gender to the color of their shoes. Although the screenshots of errors circulating on Twitter were from uncorrected proofs, several significant errors remain in the final book that bear out her critics’ misgivings. The chapters on BuzzFeed and Vice mar what is otherwise an incisive autopsy of print journalism. The major reporting lapses all occur in these lesser sections analyzing the new online wave.

But therein lies the key to understanding Abramson as a journalistic animal. She derides new digital media as much with her tone as with her reporting, and yet the very same digital journalists she maligns now wield great influence within the industry—precisely as this book contends, while failing to truly reckon with how this all came to pass. Abramson’s mistakes and the controversy she has attracted have been useful in that respect, offering both a more vivid demonstration of her own argument and pointing us toward the psychological impetus that so many autobiographers suffer: the urge to turn oneself into the center of history.

Before she was pushed out of the Times, Jill Abramson was seen within the institution as a paragon of meticulousness and a force for improving the professional lives of women journalists. She has been criticized in the press for being “stubborn and condescending” and has fallen out with colleagues over her brusqueness, but Abramson’s long career speaks for itself. Abramson does not play up her achievements at the paper of record, but instead in a single sentence notes, “By the end of my first year [as executive editor], also for the first time in history, the masthead was half female. Black, Asian, and Latino journalists won promotions, though there was not enough racial diversity at the Times or any other newsroom.”

Abramson joined The New York Times in 1997, after nine years at The Wall Street Journal. As Washington, D.C., bureau chief beginning in 2000, Abramson occupied an important perch at the Times as it misreported the government’s claims over Iraq’s supposed weapons of mass destruction, a debacle she recounts with honesty and regret in Merchants of Truth. She was named co-managing editor for news in 2003, and executive editor in 2011.

Her account of being fired in 2014 makes Merchants of Truth essential reading. Perhaps my favorite line in the whole book is her polite acknowledgment that “[t]he Times disputes parts of the account that follows and I have noted these cases.” For example, the Times does not agree that “during my eight years as managing editor, my salary lagged behind one of the male masthead editors I outranked.” It also does not agree that, as executive editor, Abramson’s salary was what her predecessor Bill Keller’s “starting salary had been in 2003, a full decade earlier.”

The gossip in these sections is of high quality. During her tenure, Abramson describes a “new ad director” who “invited the marketing directors of several car companies to the Page One meeting during the New York Auto Show,” an outrageous violation of the church-and-state division of business and editorial. She recounts a critical letter that Times Publisher Arthur Sulzberger hand-delivered to her in January 2014, describing “in shockingly personal terms” her “moodiness” and unlikeability, which she viewed as outright “sexist.” She suspected Dean Baquet, managing editor at the time, of feeding Sulzberger negative intel.

Abramson presents Baquet, who became executive editor after Abramson’s ouster, as the brittle and jealous culprit for her firing. The story essentially goes that Abramson offered a job of co-managing editor to Janine Gibson of The Guardian without consulting Baquet, because she assumed that CEO Mark Thompson was “briefing Sulzberger” and thus protecting her. Unfortunately this was not the case, and Baquet was furious that Gibson had been offered a job as his equal. “I knew Baquet liked the authority he had as sole managing editor,” Abramson admits. Baquet gave Sulzberger a “her or me” ultimatum. Abramson was not allowed to say goodbye to her staffers or to give a departing speech.

The Times is an opaque institution and these details are as delicious to read as they are rare. We learn, for example, that Thompson once demanded, over a linen tablecloth luncheon, that she focus on raising cash for the newsroom as well as running it, another breach of church and state. She snapped, “If that’s what you expect, you have the wrong executive editor.” As she spoke, “the uniformed waiter serving us spilled the water he was pouring.”

Abramson’s histories of the Times and the Post are careful accounts of how they managed the shift to digital in their operations. For a journalism nerd it’s extremely interesting, since Abramson lets us listen in on what the Sulzbergers say behind closed doors. But there are errors in Merchants of Truth and, as the Twitter firestorms pre-publication indicated, they are chiefly mischaracterizations of young media professionals.

For example, former Vice reporter Danny Gold tweeted about a “lie” he found in Abramson’s book, which remains in the final copy.* She claimed that, “In a story about an Ebola clinic in Africa, the [Vice] correspondent wore no protective clothing. In contrast, Times correspondents followed the same protocol as doctors (one reporter was herself a doctor), covering every inch of their bodies with protective clothing.” Gold responded that, “like every other reporter there,” he was “told by experts not to walk around with a PPE [personal protective equipment] unless you were in the ICU.” Furthermore, Gold said, Times reporters were given and followed the same advice. He guessed that Abramson got this “information” from a Hamilton Nolan blog post, ignoring an interview Gold himself gave her. She does cite Nolan in many places in the book. (Abramson did not respond to a request for an interview.)

The other mistakes fall into two overlapping categories: denigrating the credentials of young journalists working for BuzzFeed and Vice and poorly researching their biographies. In one section on BuzzFeed, for example, she describes how “Arabelle Sicardi, whose essays on womanhood and self-image packed more substance than most content on the site, was reassigned when her numbers lulled.” But Abramson misses the fact that Sicardi was actually pushed out after writing a post that criticized a BuzzFeed sponsor, Dove, which is a much more relevant and important story. Sicardi also uses the pronouns they/them, easily discoverable online, not she/her.

Abramson has attracted the most ire for a passage about Vice reporter Arielle Duhaime-Ross, whom she referred to in uncorrected proofs as a “transgender woman.” In the final edition, this has been edited to “a gender nonconforming woman,” but other mistakes remain. Abramson claims that Duhaime-Ross wore blue desert boots, which Duhaime-Ross says were brown, and she misstates the length of the reporter’s hair. More perniciously, Abramson frames these details within a deeply insulting portrait of Vice’s hiring procedure for on-screen reporters: “Most of the on-air talent was very young and had scant experience; only three had ever reported on camera before. What they had was ‘the look.’ They were diverse: just about every race and ethnicity and straight, gay, queer, and transgender. They were impossibly hip, with interesting hair.”

Abramson claims that Duhaime-Ross had “no background in environmental policy”; in fact, she has a master’s degree in science, health, and environmental reporting, as her website states. She writes of Duhaime-Ross: “Biracial, she identified as black.” She adds, “She almost missed one of the most important stories on her beat,” about Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord. Duhaime-Ross did not, in fact, almost miss that story. And the detail about her ethnicity reads as an accusation that Duhaime-Ross cynically played the minority for career gain.

In a recent interview with The New Yorker’s Isaac Chotiner about this incident, Abramson claims that she “meant no put-down” in this section, and that her point about Duhaime-Ross’s lack of experience was that she seemed “enterprising.” “No one corrected me. The transgender thing was an error,” she said, “and I corrected it for the final book.”

Abramson’s focus on younger journalists’ appearance sticks out like a sore thumb. In one section praising Cory Haik of The Washington Post, for example, she notes that this “native digerati ... looked perfectly cast for her role as digital innovation czar,” because she had “two-tone hair (with a scarlet streak), and wore extremely high heels and cool leopard-print dresses.” Repeatedly, Abramson writes about “cool points” as if they are an influential yet ultimately worthless metric in digital publishing, implying that it leads publications to hire inexperienced journalists. In describing a 2016 BuzzFeed party, for example, she derides its “self-congratulatory levity.” When Vice sent Dennis Rodman to North Korea in 2013, she calls it “scoring cool points like its business depended upon it, which was true.” What of the fact that Rodman gained access where few else had? Is Dennis Rodman “cool,” anyway, and if he is, didn’t Vice prove that “cool” has a function in reporting on North Korea?

These sections read like Abramson is speaking from a place of ill-informed bitterness over print’s loss of supremacy. They also speak to her failure as an interpreter of how media has changed. When she describes BuzzFeed’s hire of Katie Notopoulos, Abramson writes that she had no background in the news business. While it’s true that Notopoulos did not have a full-time media job prior to her hire, she was well known for her many excellent essays about internet subculture. To me, Notopoulos was a distinguished freelancer; to Abramson, she was a person with an “off-hours hobby.”

Abramson even maligns young Times staffers, writing about “the more ‘woke’ staff” who see “social media feeds as platforms for free exchange, not to be monitored or censored by editors,” the kind of employee who “looked to younger, newer editors like the Style section’s Choire Sicha and the editor of the Times Magazine, Jake Silverstein, for inspiration, rather than to the more distant and older masthead.” It’s abundantly clear what type of journalist she understands and cares about insulting, and which she does not.

Unfortunately, Abramson specifically charges new digital media with a neglect of fact-checking. In a section on Vice’s Thomas Morton reporting in Uganda, for example, she notes that he mistakenly called it the “drunkest place on earth.” She goes on: “The assertion fell apart after it was fact-checked, but it wasn’t fact-checked until it was published, and even then the fact-checking was done by an independent journalist who felt it necessary to hold Vice accountable.”

The irony is thick. Several articles followed the initial Twitter backlash to Abramson’s proofs, decrying the lack of fact-checking in book publishing. In her New Yorker interview, oddly, Abramson explains that the book was actually fact-checked. So how did certain errors make it into the final book? One answer is that Abramson was intent on shoring up a conclusion that she had reached well before she began her reporting: that digital media is sloppy, irreverent, not serious. But another possibility is that some of her statements simply read as false to “us,” by which I mean digital-native writers who have made their careers online.

Abramson’s rudeness to “woke” writers misses something crucial: the very serious political convictions that inform the work of younger journalists. Empathy for other people, an outspoken concern for gender equality, a recognition of the personal and professional stakes of representation: these are fundamental principles in new digital journalism, not afterthoughts. The misgendering is the perfect example. It’s a generational blind spot for Abramson. It does not occur to her to check pronouns, because among her professional milieu it has not been a priority.

If Merchants of Truth had focused on the Times and the Post alone, it would have been an excellent contribution to the history of journalism. So why did Abramson step out of her zone of expertise to profile digital media? It’s tempting to see the answer in the circumstances of her own career. If the younger generation suffers from a lack of traditional newsroom training in fairness and ethics and reporting, then the loss of Jill Abramson means something.

Of course, losing her did mean something to many people at the Times. But Abramson’s narrative insists on a meeting of the personal and the historical, when her ouster could more easily be chalked up to factors that are as timeless as they are petty: the machinations of an underling, say, who wants to be king. What we’re left with is half of a great book, and half of a book that recommends to other late-career journalists that they take their inheritors seriously. The digital natives now have loud voices, magnified by the authority of their political convictions. You have to meet change on its level—especially if you’re trying to sell the truth.

*A previous version of this article incorrectly identified Danny Gold as a Vice reporter. He is no longer with the company.

Whether you're looking for a sub-$1,000 system that runs mid-range games or a VR-ready battle station, we've found your deal.

Whether you're looking for a sub-$1,000 system that runs mid-range games or a VR-ready battle station, we've found your deal.

No comments :

Post a Comment