Ben Terris calls it “Pundititis.” Democrats still haven’t recovered from the trauma of Hillary Clinton’s loss to Donald Trump, and it’s causing them to wring their hands about every candidate emerging to challenge him in 2020. So the Washington Post reporter coined this term to describe “a virus affecting the nervous system of Democratic voters that was born out of the 2016 elections. Those infected find themselves unable to fall in love with candidates, instead worrying about what theoretical swing voters may feel. Signs of Pundititis include excessive electoral mapmaking, poll testiness, and an anxious, queasy feeling that comes with picking winners and losers known as ‘Cillizzasea’”—a dig at Terris’s former colleague.

This is not an inaccurate diagnosis of the Democrats today. Terris is also right to attribute this malady not only to the results of the last presidential election, but to the mainstream media’s analysis of the emerging Democratic field. Reading much of the punditry of late, one might expect the primary season to be the political equivalent of WWE’s Royal Rumble, a massive free-for-all in which the candidates beat each other to a pulp in a race to the left, leaving one wobbly—and perhaps not very “electable”—candidate standing for Trump to effortlessly defeat.

Fear not, afflicted ones. While Democrats are understandably scarred by 2016, the party has learned its lesson: There will be no coronation this time around, no stark contrast between two candidates representing their respective wings of the party. And while the 2020 primary thus will be crowded, it will be a marked contrast to the “clown car” Republican primary of 2016. For the next year, the Democrats will showcase a party that looks and sounds very different not only from the GOP, but from the Democratic Party of just a few years ago. Rather than a moment of anxiety, this should be a moment of hope and pride—and Republicans should be the ones feeling queasy.

Democrats are gearing up for a long, contentious primary season. Nine major candidates have already entered the fray—most recently South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, an openly gay 37-year-old military veteran, who announced on Wednesday. By the summer, that number may have ballooned to two dozen or more. That vast field will reflect the Democratic Party in all of its diversity, from ideology to race to sexual orientation to, yes, age. But that has some Democrats nervous that the unfolding contest will distract from the only thing that matters: beating Trump.

The New York Times’ Jonathan Martin characterized these concerns thus: “Will candidates sprint to the left on issues and risk hurting themselves with intraparty policy fights and in the general election? Or will they keep the focus squarely on Mr. Trump and possibly disappoint liberals by not being bolder on policy?”

This is certainly how some Democrats see it: that the candidates can either engage in a costly intraparty fight about issues like Medicare for All and the Green New Deal, or they can focus their fire on the real enemy. The urgency to distinguish oneself from two dozen competitors suggests it will be more the former than the latter. But does that necessarily mean whoever emerges from this scrum will be weakened by it? Couldn’t the opposite be true? Might the nominee be even stronger for their contest against Trump?

Not if the nominee is unelectable, say the pundits.

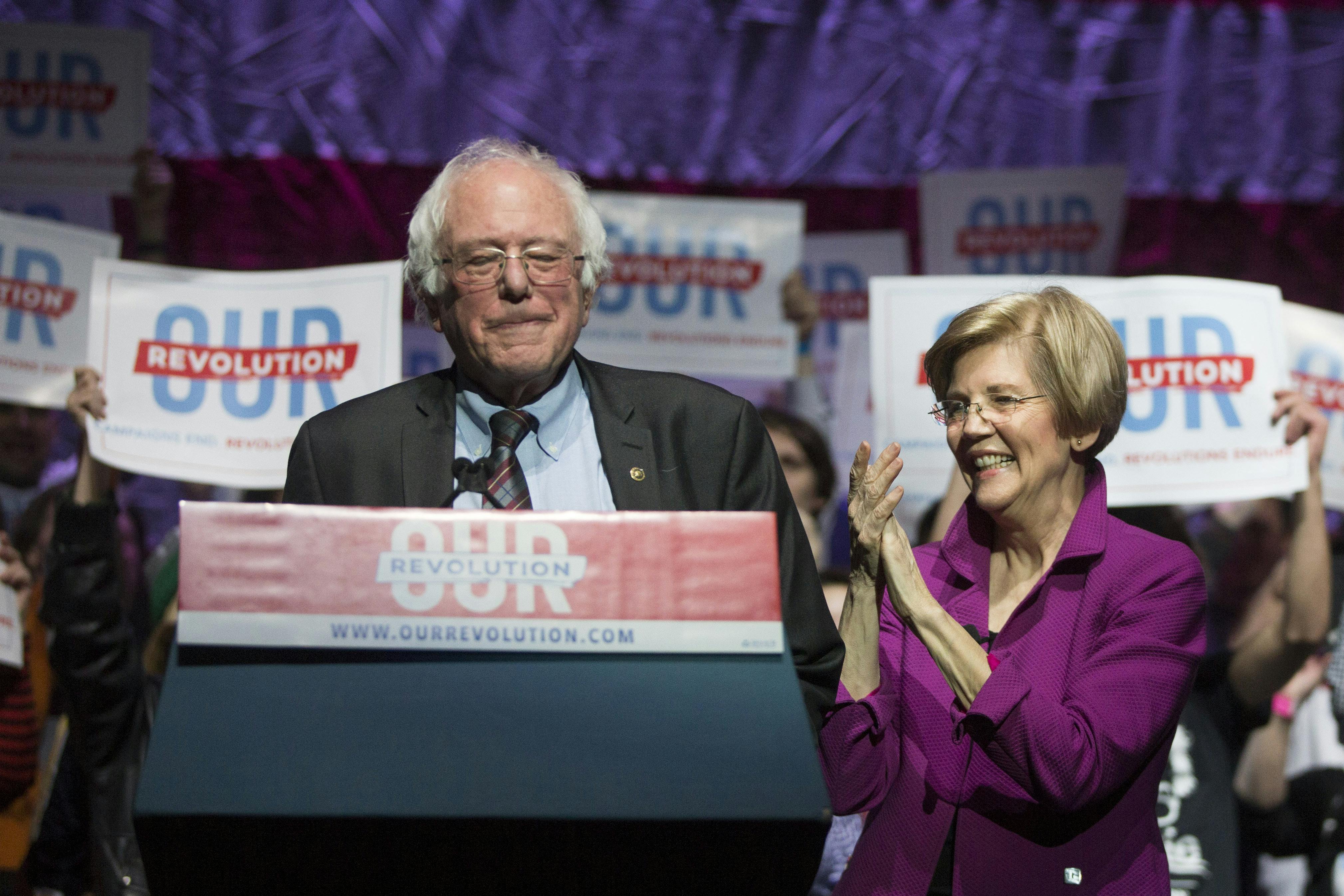

This concept of “electability”—of who is best positioned to win the general election, as opposed to the primary—has driven much of the discussion about the Democratic contenders. Some pundits have even gotten scientific about it: CNN’s Harry Enten crunched the numbers to determine that Amy Klobuchar and Sherrod Brown are electable, while Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are not.

But others have rightly questioned such analyses. “How, exactly, can anyone tell who the strongest candidate is before an election?” Terris asked. “The simple answer is, they can’t.” Hillary Clinton “was so ‘electable’ that she nearly cleared the field,” he added. “Then she wasn’t elected.” Trump, conversely, was seen as unelectable from the moment he entered the GOP primary until the evening of November 8, 2016. As New York magazine’s Eric Levitz has argued, “Electability arguments have always been handy stalking horses for substantive disagreement.” Which is perhaps why leftist candidates like Warren are being painted as unelectable, while potential centrist ones like Beto O’Rourke and Joe Biden are being treated as Trump’s most formidable foes.

In the end, the gauntlet of the Democratic primary will be the best vehicle for determining who the party’s best candidate is. And there are plenty of reasons to believe that gauntlet won’t be as taxing as some fear it will be.

The 2016 contest between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders was much tamer than it was made out to be. All but a quarter of one percent of the two candidates’ advertisements were positive ads. The authors of Identity Crisis found, moreover, that “Sanders’s success was not so much about capitalizing on an early reservoir of discontent with Clinton. It was about building support despite her popularity in the party.” A higher percentage of Sanders voters voted for Clinton in 2016 than Clinton voters did for Obama in 2008. For all the ink spilled about the acrimony between “Bernie bros” and Clinton die-hards, the primary almost certainly did not play a major role in her loss to Trump.

The 2020 primary undoubtedly will fuel a lot of animosity online, too, but there’s no reason to believe that it will be particularly acrimonious among the candidates themselves. There appears to be broad agreement, both on the need to repudiate the Trump administration and the necessity of passing bold reforms. Moreover, there appears to be no Trump-like outsider waiting in the wings to upend the race and cause an existential crisis in the party.

Yes, there will be intense scrutiny of the candidates—from Kamala Harris’s mixed record as a federal prosecutor to Joe Biden’s support for overly punitive crime bills—but that’s to be expected, and necessary. There’s no reason to believe that a lengthy debate about ideological differences in the party will be harmful. Democrats have been engaged in exactly that for the past two years, and they have paid little to no political price. They won 40 House seats in a historic midterm election, and every well-known Democrat currently leads Trump in early 2020 polling.

The policy questions that remain—on universal health care, humane immigration, economic redistribution, and so on—are ones worth debating, not just as a party but a country. The Republicans are largely bankrupt of ideas, leaving Democrats alone to put forth concrete, comprehensive proposals for fixing America’s most vexing social and economic problems. Given the unpopularity of Trump’s agenda, what could be more electable than that?

Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives, recently handed President Donald Trump a way to cancel next week’s State of the Union address without losing face. Instead, he refused her offer, setting in motion a standoff that has uncomfortable parallels to—if also important differences with—a pivotal moment in the history of English democracy.

In a letter last week, Pelosi noted that Secret Service agents and Department of Homeland Security officials had been furloughed by the shutdown. “Sadly, given the security concerns and unless government re-opens this week, I suggest that we work together to determine another suitable date after government has re-opened for this address or for you to consider delivering your State of the Union address in writing to the Congress on January 29th,” she wrote.

Trump waited until Wednesday to reply, declaring that there were no security concerns that would prevent his appearance. “I look forward to seeing you on the evening on January 29th in the Chamber of the House of Representatives,” he wrote to her. “It would be very sad for our Country if the State of the Union were not delivered on time, on schedule, and very importantly, on location!”

There isn’t much precedent for an American president threatening to storm the House over the speaker’s objection. While Trump has the right to be in the chamber, as CBS News’ Ed O’Keefe notes, he can’t address the House and Senate without their joint approval. And he does not have Pelosi’s. Hours after Trump’s letter, she replied that she would not consider a motion to hold the State of the Union until the shutdown ended. “Again, I look forward to welcoming you to the House on a mutually agreeable date for this address when government has been opened,” she wrote.

Should Trump choose to ignore Pelosi, and attempt nonetheless to give his State of the Union at the House next Tuesday, it would echo one of the uglier chapters of the British monarchy.

Charles I, who reigned over England, Scotland, and Wales from 1625 to 1649, never enjoyed good relations with Parliament. England was a largely Protestant country with a strong tradition of parliamentary government, but Charles, who had married a French Catholic queen, believed in a king’s absolute right to govern.

Charles had refused to convene Parliament for eleven years, to avoid any checks on his power. But to secure funds for a war against unruly Scottish nobles to the north in 1640, he faced the ancient dilemma of English kings. Parliament’s consent would be needed to levy any new taxes, but it was unlikely to be given without concessions by the crown.

Relations between members of the new Parliament and the king quickly disintegrated after he summoned it in 1640. The House of Commons and the House of Lords passed laws to strip away his powers, attaching funds to them so he would give royal assent. With most of Europe still consumed by religious turmoil, many Protestant members feared Charles was part of a foreign plot to restore Catholicism over England. In 1642, tensions came to a head. Charles issued a warrant for the arrest of five key members of the Commons for high treason.

The Commons refused to immediately hand them over. The following day, armed soldiers arrived and broke open the doors, and Charles himself entered the chamber to personally arrest the members. All five of them had already fled, however. Charles then turned to the speaker to ask where they had gone. “May it please your majesty, I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak in this place but as this house is pleased to direct me whose servant I am here,” the speaker famously replied, reasserting the legislature’s privileges. Charles’s act was a brazen violation of England’s unwritten constitution. He was the first monarch to set foot in the House of Commons, and none of his successors have dared to do so again.

Granted, as bizarre as politics have become Trump, such a scene is implausible in modern America. And the stakes today are nowhere near what they were 1642. The king stormed Parliament to arrest five of its members on allegations of treason, not to give a speech outlining his policy agenda. Charles’s actions also directly precipitated a civil war that ultimately ended his reign. While relations between the House and the American president are currently frosty, to say the least, there is no risk of open warfare between the two sides.

What both rulers share is a disdain for the very idea of political opposition in the legislative branch. After Pelosi’s announcement, Trump told reporters that the Democratic Party under her leadership was a “very dangerous party for this country” and that he was “not going to allow the radical left to control our country.” He regularly casts the debate over border-wall funding as an existential struggle against Democrats who want to bring criminals and drugs into the United States. Delegitimizing political opponents is one of Trump’s favorite tactics, whether against media outlets that report on him or federal judges who rule against him.

Trump is also driven by his personal whims, often to the detriment of his and his party’s policy goals. His presidency has been defined by his inability to work alongside lawmakers, even when both chambers were controlled by Republicans. His approach to negotiating with congressional Democrats has been to issue ultimatums, then wait for them to move in his direction. He causes crises, then uses them to force concessions. This strategy may satisfy his desire to wield leverage over his opponents in the short term. But it has also hardened Democrats against giving into his demands and intensified the American public’s opposition to his policies.

As the year progresses, these disputes will only get more pronounced. House Democratic lawmakers are planning a battery of oversight hearings into the past two years of his administration. There will be inquiries into White House security clearances, the politicization of the Census, the acting attorney general’s tenure at the Justice Department, and much more. Michael Cohen, Trump’s former personal attorney, was slated to testify before Congress next month but requested a delay, citing threats against his family. The intense scrutiny will only deepen Trump’s desire for a subservient Congress.

Trump hasn’t yet decided what to do now that Pelosi has rebuffed him. The New York Times reported Wednesday that he’s exploring alternative venues for his address. But he could instead take a page from Thomas Jefferson, who in 1801 began a century-long tradition of submitting the State of the Union to Congress in writing instead of delivering it as a speech. Jefferson opposed the prospect of a presidential speech because he thought it too reminiscent of the British monarchy. For Trump, however, that may be part of the allure.

Update: Trump announced on Twitter late Wednesday evening that he would postpone his State of the Union until after the shutdown ends.

The fraught situation in Venezuela seems to be coming to a head. On Wednesday, 35-year-old opposition leader Juan Guaidó declared himself interim president following widespread protests calling for the resignation of strongman Nicolás Maduro, the president and leader of the so-called Bolivarian Revolution that began under Hugo Chávez in 1999. Guaidó was quickly recognized by the United States, Canada, and Brazil. Mexico, under the new administration of leftist Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador, did not endorse Guaidó. In Russia, a key Maduro ally, members of parliament condemned the U.S. recognition, calling Guaidó’s move a “coup.” China, which has helped shore up Maduro’s government in the past, remained silent.

By openly calling on foreign governments for support, Guaidó, an engineer who presides over the country’s National Assembly, presents the sharpest and most consequential threat yet to Maduro’s regime. In recent weeks, Venezuelan opposition leaders have intimated that Maduro is vulnerable and that a small show of force would be enough to force his ouster. Their goal was almost certainly to nudge friendly right-wing governments in Brazil and the United States toward supporting regime change. It remains unclear, however, that the military has turned decisively against Maduro, setting up the possibility of a far-reaching and deadly armed confrontation should Maduro resist ousting. Even if the armed forces have abandoned the president, the drastic step of removing him by force is unlikely to pacify this deeply divided nation. It would almost certainly make a bad situation worse.

Earlier this month, Jorge Borges, an exiled opposition leader whom Maduro has accused of plotting his assassination, explained that the president “remains in power, fundamentally, due to two things: the support of the military—really just the upper ranks—and the dictatorial know-how of the Cubans.” Other than that, Borges noted, “Maduro has nothing. There’s no economic support, no diplomatic support, no political support ... I think he’s irredeemably defeated and it’s impossible for him to overcome the crisis he’s created.”

If the regime lacks popular support now, that wasn’t always the case. Venezuela managed to secure real material and social gains for its poorest citizens under Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez. With the end of the so-called commodity boom following the global 2008 crash, however, Venezuela began a slow-motion process of economic collapse that the government has been unable to reverse. As a former advisor to Chávez put it in a recent interview, “even if it’s sensationalized in the international press, the Venezuelan government also suffers from a lack of transparency, from corruption, and there is a general problem of mismanagement, lack of technical skills, and of qualified people in the right places.” Maduro, a Chávez protégé, narrowly won the race to succeed him in 2013. In 2018, Maduro won a second term in an election many consider to have been rigged. As economic conditions have worsened in recent years, the regime has hardened to the point that the government can no longer be considered fully democratic. In May 2018, a 400-page independent report published by the Organization of American States concluded that Maduro bore responsibility for a litany of human-rights abuses: murders, extra-judicial executions, and torture, in addition to the ongoing humanitarian crisis linked to economic ineptitude.

Comparing one part of the world to another is always a risky proposition, but the 2003 Iraq War carries important lessons.For the Trump administration, this is sufficient grounds to push for Maduro’s removal. In an official statement responding to Guaidó’s proclamation, Donald Trump called the National Assembly led by Guaidó “the only legitimate branch of government duly elected by the people” and declared that “the people of Venezuela have courageously spoken out against Maduro and his regime and demanded freedom and the rule of law.” In response, Maduro gave U.S. diplomats 72 hours to leave the country. “The United States does not recognize the Maduro regime as the government of Venezuela,” U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo replied in a statement shortly thereafter. “Accordingly, the United States does not consider former president Nicolas Maduro to have the legal authority to break diplomatic relations with the United States or to declare our diplomats persona non grata.”

Open conflict remains unlikely, particularly since the governments that in the morning recognized Guaidó’s claim to the presidency added by the late afternoon that they would not themselves expel Maduro from the presidential palace. But that unnerving prospect looms over escalating diplomatic tensions.

Venezuela is a quagmire that defies simple solutions. Even if Maduro were to fall easily with international intervention, as the opposition claims he would, the aftermath is sure to be calamitous and possibly even worse than the status quo. This is to say nothing of the illegality of such a strike—despite the moral, political, and economic failures of Maduro’s leadership—or the dismal record of U.S.-supported efforts at regime change.

Comparing one part of the world to another is always a risky proposition, but the 2003 Iraq War carries important lessons. On September 14, 2003, Vice President Dick Cheney infamously declared that invading U.S. troops would be “greeted as liberators.” For now, notwithstanding the protestations of Republicans in Congress, the American people seem inoculated against such presumption when it comes to Venezuela. There is little appetite for “boots on the ground,” perhaps in recognition of the moral and strategic blunders of previous ham-fisted attempts to shape global affairs.

As was the case with Iraq, there is no clear plan for what comes next in a post-Maduro Venezuela in the event of an intervention unsanctioned by international law. As Matias Spektor, a professor of international relations at Brazilian university Fundação Getúlio Vargas, noted on Twitter Wednesday afternoon, Guaidó “has no plan for a political transition, no united base, does not control the movement in the streets and there is no organized machinery in the country. He also has no agreement with the Armed Forces, an actor without whom there will be no transition to a democratic government.” President Barack Obama recently said that insufficient planning for a post-Gaddafi Libya was his single biggest regret. Although Trump has shown no disposition to learn from his predecessors, the country, the region, and the world would undoubtedly benefit if he took a lesson from Bush and Obama in this instance, particularly given the distinct possibility that any conflict in Venezuela would spill over into neighboring Brazil, or already-unstable Colombia.

Maduro’s government deserves profound condemnation. But the context in which Wednesday’s escalation has taken place matters. Getting tough with Venezuela comes at a politically opportune moment for both Brazil’s far-right new president Jair Bolsonaro and Donald Trump, allowing the former to distract from a disastrous first trip abroad and a scandal involving his son and the latter to project strength amid a government shutdown with no end in sight. While the United States and Brazil both ruled out directly military strikes against Maduro, Trump and Bolsonaro have ample motivations to make hay of regime change abroad. Both men may find that a widely reviled figure like Maduro makes for an attractive—and expedient—foil. The challenges in both the U.S. and Brazil are to make sure such immediate incentives don’t overwhelm prudence.

If you're still on a Windows 10 Mobile device, this is the year to jump to another platform. Microsoft will cease support for the mobile operating system on December 10.

If you're still on a Windows 10 Mobile device, this is the year to jump to another platform. Microsoft will cease support for the mobile operating system on December 10.

No comments :

Post a Comment