What happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object? The unstoppable force declares a national emergency to go around it.

That option appears to be President Donald Trump’s endgame to resolve the current standoff over the border wall. His demand that lawmakers provide $5.7 billion for a concrete barrier along the nation’s southern border led to a partial government shutdown that is now in its twentieth day. More than 800,000 federal workers, many of whom live paycheck to paycheck, are now furloughed or working unpaid, causing food safety inspections, airport security, and much more to slow to a crawl.

Now that Trump has backed himself into a political corner, an emergency declaration seems like the least humiliating way for him to reopen the federal government without bending on his central campaign promise. “Probably I will do it,” he told reporters on Thursday morning outside the White House. “I would almost say definitely. If we don’t make a deal, I would say it would be very surprising to me that I would not declare a national emergency.”

What would that entail? The legal mechanics are pretty straightforward, though a court battle would certainly follow. Two provisions in federal law could give Trump the off-ramp he seeks. One allows him to order the Army Corps of Engineers to work on construction projects deemed “essential to the national defense” during a declared emergency, while another allows the president to spend defense-related funds on those projects without a specific appropriation from Congress. In essence, Trump would be robbing the Pentagon to pay for the wall.

Given Trump’s authoritarian tendencies, many Americans are understandably worried about the consequences of his declaring a national emergency to satisfy a short-term political objective. “Of the 58 times presidents have declared emergencies since Congress reformed emergency-powers laws in 1976,” The New York Times notes, “none involved funding a policy goal after failing to win congressional approval.”

But such a move, while hardly inspiring confidence in the state of the American political system, also wouldn’t represent a tipping point toward dictatorship. Trump would deserve plenty of criticism for wielding his executive power like a kid with a loaded handgun, but lawmakers past and present wouldn’t be blameless in the matter. They put the gun in his hands.

The phrase “state of emergency,” especially when invoked by a president who shows little interest in preserving democracy, rightly sends a chill down spines. It’s virtually synonymous with dictatorship and illiberal putsches. Not every leader who declares a state of emergency is a dictator, of course, but almost every dictator invokes them at one time or another. Perhaps the most familiar example came after the Reichstag fire in 1933, when German lawmakers declared a state of emergency that set Adolf Hitler on an irreversible path toward totalitarian rule. Some Trump critics, in accordance with Godwin’s law, have hyperbolically invoked this history:

A national emergency?

What happened?

Did an illegal immigrant set fire to the Reichstag?

Government shutdown: Will President Trump declare a national emergency? - CNNPolitics https://t.co/0ix6XutwV1

But Trump, unlike Hitler, would not be suspending the Constitution or usurping Congress’s power. He’d be using a moribund provision of federal law written by Congress itself. Lawfare’s Quinta Jurecic noted earlier this week that, dismal optics aside, Trump may be on relatively safe constitutional grounds when his actions reach the courts. “This is not ‘sovereign is he who decides on the exception,’” she wrote, “but a president exercising power delegated to him by a co-equal branch of government consistent with the structure of separation of powers—and likewise subject to review in litigation by another co-equal branch of government.”

How did we get here? Elizabeth Goitein, a legal scholar at the Brennan Center for Justice, explored the history of federal emergency powers in a recent article in The Atlantic. She noted that most of these powers accumulated over the twentieth century—and especially during World War II and the Cold War—as tools for presidents in moments of great crisis. After Watergate, Congress passed the National Emergencies Act of 1976 to impose new checks on the powers they had already given up.

“By any objective measure, the law has failed,” she wrote. “Thirty states of emergency are in effect today—several times more than when the act was passed. Most have been renewed for years on end. And during the 40 years the law has been in place, Congress has not met even once, let alone every six months, to vote on whether to end them.” The Brennan Center tabulated 123 duly-passed laws that grant the executive branch sweeping new powers at the president’s discretion, including the ability to lawfully commandeer telecommunications systems and declare martial law.

The lawmakers of an earlier age thus made an egregious oversight: They assumed that future presidents would use these extraordinary powers in good faith, to address genuine national emergencies. The Trump administration is a monument to their lack of foresight. In an unhappy syzygy, the areas where Congress has ceded the most power and the broadest discretion—immigration and national security—also happen to be Trump’s favorite playgrounds for both policy and politics.

Take the current state of the Temporary Protected Status system. Congress set it up in 1990 to give temporary legal status to foreign nonimmigrants in the United States if they are fleeing extraordinary hardship in their home country, such as civil war or a major natural disaster. Trump’s predecessors used it to shield migrants from El Salvador, Haiti, Nicaragua, and seven other countries from deportation. Trump used that discretion to decline to renew legal status for most of those groups. More than 200,000 people, some of whom who had spent more than two decades building lives in the U.S., are now at risk for deportation when their status expires over the next few years.

The administration has an uncanny knack for exploiting oft-overlooked provisions in American immigration law. Trump ad-libbed his first proposal for the Muslim travel ban on the campaign trail in December 2015, originally describing it as a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” No law authorizing such a ban would ever make it through Congress today. Nonetheless, he was able to implement a ban on several Muslim-majority countries by citing a provision in a 1952 federal immigration law that allows the president to “suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens” for an indefinite period if he deems their entry to be “detrimental to the interests of the United States.”

Why did Congress give the president such sweeping powers? The State Department’s Office of the Historian noted that two of the law’s authors, Nevada Senator Pat McCarran and Pennsylvania Representative Francis Walter, had previously “expressed concerns that the United States could face communist infiltration through immigration and that unassimilated aliens could threaten the foundations of American life.” The Supreme Court also typically gives its broadest level of deference to presidential power when it is invoked in the name of national security. Those precedents led the justices to narrowly uphold Trump’s travel ban last June, effectively sanctifying the most bigoted presidential act in modern American history.

Congress’ past foolishness does not excuse Trump’s current actions, but a declaration of emergency for political gain would not mark a terminal slide into authoritarian rule. It might even do some good by shining a spotlight on the mistakes and misjudgments of past Congresses—and providing powerful evidence of the need for lawmakers to claw back the legal authority that was too freely granted to presidents over the past century.

In his 2015 book The Republic of Conscience, former U.S. Senator and presidential candidate Gary Hart identifies what may be the central dynamic of American political and economic history: the struggle to accommodate the interests of a commonwealth with a capitalist economic system. “There has never been a serious effort to convert the United States to socialism or widespread public ownership,” he points out. “There have been continuing efforts, even today, to convert much of our publicly owned resources to private ownership and development.”

As Hart explains, we enjoy two different kinds of public resources—natural resources, such as land, water, and wilderness; and built public infrastructure, such as transportation systems, recreation areas and facilities, and public schools. The question of which resources should be administered by public agencies on behalf of everyone and which should be subject to the private interests of corporations and shareholders is and will remain passionately contested in politics. Hart argues that the citizens of a commonwealth are obliged to preserve public resources not only for their own benefit but for the sake of future generations. “The charters of few if any private corporations include concern for the well-being of future generations,” he comments, rather bitterly.

Hart observes elsewhere that the United States is heir to two distinct and venerable politico-philosophical traditions, that of liberalism and that of republicanism (which is often referred to nowadays as “civic republicanism,” to avoid any confusion with the Republican Party). The central focus of the liberal tradition is on the rights of individual citizens to be free of interference by government in their private affairs. The republican tradition, on the other hand, concerns itself with the public arena, and the right—which is also an obligation—of citizens to participate fully in the political affairs of their community in determining its collective destiny. This republican version of freedom has been called “public liberty.”

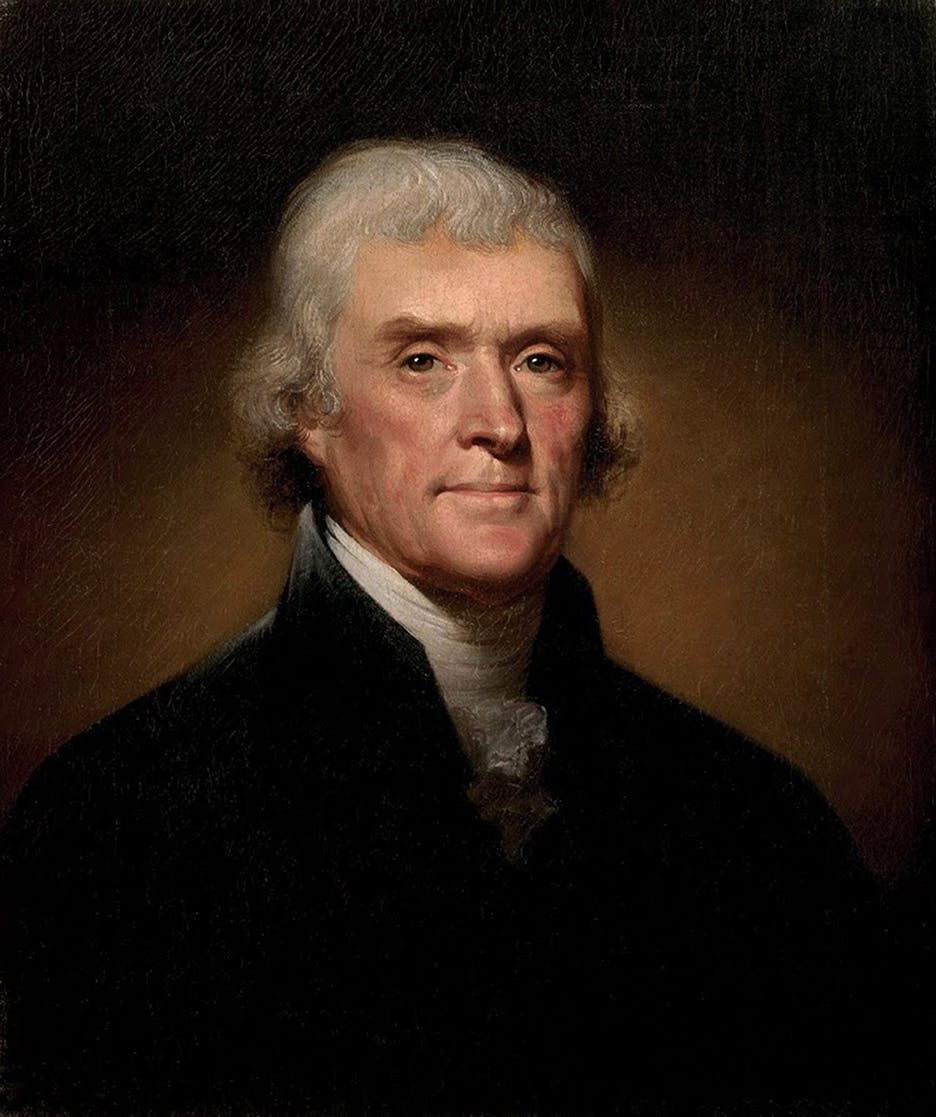

Many commentators have considered the two contrasting philosophies to be incommensurable—so divergent in their essentials, in other words, as to resist being judged by the same standard. Thomas Jefferson accepted John Locke’s thesis that people possessed the grand, overarching, natural rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” Hart writes, as well as more mundane ones such as the rights of speech, assembly, and worship, and to a jury trial by peers. But Jefferson added to that liberal stance the republican stipulation that such rights would never be secure without active citizen involvement in the governmental process.

What light could Jefferson’s—and Hart’s—hybrid philosophy cast on the political situation in the United States today? First of all, the line between the public and private domains, between the search for the common good and the quest for private gain, is not only being eroded under the Trump presidency but nearly obliterated. Trump regards the presidency as a business opportunity for him and his family, not a chance to render public service to the nation. Under his administration, there has been a mad rush to turn over invaluable public resources, such as national park land, for private exploitation. His Secretary of Education, Betsy DeVos, is committed to privatizing public education throughout the country, regardless of the miserable failure of charter schools sponsored by her and her family in their home state of Michigan.

America has increasingly come to define itself as a democracy rather than a republic. What’s more, Americans interpret “democracy” in increasingly narrow terms, as almost a synonym for capitalism, and as indicating a regime that functions primarily as a guarantor of rights. It is noteworthy, therefore, that President Trump has called into question America’s most sacrosanct right, the right to free speech embodied in the First Amendment, in his relentless attacks on the press, and that the Republican Party (so-called) has adopted as one of its foremost political tactics a campaign to suppress the voting rights of various minority groups.

None of this will surprise adherents of republican philosophy. Republican theorist Quentin Skinner has written, “The reason for wishing to bring the republican vision of politics back ... is simply because it conveys a warning which ... we can hardly afford to ignore: unless we place our duties before our rights, we must expect to find our rights themselves undermined.” Liberal principles alone are not sufficient to thwart the designs of a would-be tyrant.

Several years ago, instead of getting up to go to my well-paid, secure job as a tenured college professor, I would lie in bed for hours, repeatedly watching the video to “Don’t Give Up,” Peter Gabriel’s duet with Kate Bush. “I am a man whose dreams have all deserted,” Gabriel sings, echoing my inner monologue. I tried to believe Bush’s compassionate refrain, “Don’t give up, ’cause you have friends,” but I just couldn’t. My first class was at 2 p.m.; I’d make it there barely on time and barely prepared, then go right back home. At night, I ate ice cream and drank malty, high-alcohol beer—often together, as a float. I gained 30 pounds.

The antidepressants my doctor prescribed didn’t help. My psychotherapist told me I didn’t have clinical depression. Eventually, I realized something different had happened, something that lacks an official diagnosis. I had burned out.

In a recent BuzzFeed essay, “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation,” Anne Helen Petersen gives a thorough account of how our society, especially in the past few decades, has ensured mass burnout by demanding more education, more debt, and more willingness to put work ahead of everything else. Petersen—who, full disclosure, is a friend who has cited my writing on burnout—coins the term “errand paralysis” to describe her inability to perform the small, ordinary tasks we associate with functional adulthood. She makes a convincing case that, despite our society’s moralistic view of work, burnout is not the worker’s fault.

Petersen’s essay, which went viral, clearly resonated with young Americans. But by focusing on millennial burnout, Petersen understates the scope of the problem. About a quarter of all U.S. workers, of all ages, exhibit key symptoms of burnout—and it’s likely that many more workers have experienced burnout at some point in their lives. This isn’t a generational epidemic; it’s a societal one.

According to research psychologists, burnout has three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (or cynicism), and the feeling of personal inefficacy. To measure it, they administer a questionnaire called the Maslach Burnout Inventory, named for Christina Maslach, a leading burnout researcher for four decades. Maslach and her coauthor, Michael Leiter, identify six main causes of burnout that arise within organizations: too much work, lack of control, too little reward, unfairness, conflicting values, and the breakdown of community. If you experience these in your job for long enough, you’re likely to go home every day feeling empty, bitter, and useless.

If Petersen was exhausted, it’s no wonder. “I was publishing stories, writing two books, making meals, executing a move across the country, planning trips, paying my student loans, exercising on a regular basis,” she explains. “But when it came to the mundane, the medium priority, the stuff that wouldn’t make my job easier or my work better, I avoided it.”

I know the feeling. Once I got tenure, securing a lifetime of job security, I had it made. The feeling lasted a year. After a post-tenure sabbatical, I returned to a college facing budget and accreditation crises. There was suddenly much more work to do and after a round of layoffs, fewer people to do it. I did good work, but didn’t feel that it was recognized by higher-ups. It was also dispiriting to teach students a subject—theology—that the college required them to study, but which they didn’t really want to learn about. My wife, also an academic, was working in another state. When I took the Maslach Burnout Inventory three years ago, at age 40, I landed in the 98th percentile for exhaustion.

Millennials face a characteristic set of pressures, but older generations experience widespread burnout too. I was relatively young when burnout struck, but I’m squarely in Generation X. I hear constantly from people my age and older about how their work has used them up, but they feel they must keep going. Maslach’s original research, in which she recognized a growing burnout crisis in fields like nursing, social work, and law enforcement, involved workers born prior to 1960. The conditions she and Leiter say foster burnout have been characteristics of American workplaces for a long time. They affect workers of all ages.

In medicine, the field where burnout has been studied most thoroughly, burnout rates are actually lowest for the under-35 cohort of doctors but increase through middle age and decrease again for physicians over 55. Given the pay and prestige of a medical career, as well as the tremendous debt most people take on to enter the profession, it’s not surprising that doctors would be reluctant to quit even when they’re past the point of exhaustion. By doing so, however, they may jeopardize their quality of care. When one worker burns out, their patients, coworkers, and customers suffer, too.

In the end, even Kate Bush’s counsel wasn’t enough to cure my burnout. I resigned my position, sunk costs be damned. My wife and I live under the same roof now, and I’m lucky to be married to someone with stable work and good benefits, since I took a 75 percent pay cut in becoming a freelance writer and adjunct instructor at a nearby university.

Quitting worked for me, but this solution doesn’t scale up very well. So what can we do about mass burnout? Petersen is right that individual solutions—meditation, saying “no” to excessive work demands—may be appealing, but won’t solve the deeper problem.

I mean all those things are great but they're not actually burnout cures, they're ways to optimize your mind and body for more and better work

— Anne Helen Petersen (@annehelen) January 5, 2019Because the causes are systemic, the solution to burnout will need to be too. Peterson noted why “many millennials increasingly identify with democratic socialism and are embracing unions: We are beginning to understand what ails us, and it’s not something an oxygen facial or a treadmill desk can fix.” But overthrowing capitalism isn’t a complete solution, either. The things that cause burnout – from overwork and shoddy management to a lack of recognition – would likely persist in socialist systems. Workers burn out in social democracies like Sweden, too.

We can’t just throw cash at the burnout problem, either, like Don Draper does on “Mad Men” when his younger business partner Peggy Olson complains that her tireless work goes unrecognized. “That’s what the money is for!” he bellows. Of course, workers would benefit from higher wages, but a bigger paycheck won’t keep you from burning out if you’re treated unfairly, or your employer’s values differ from yours, or your boss is a tyrant. Besides, burnout isn’t just a reaction to bad jobs. I had a great job, but there were still problems with my workload and rewards I couldn’t bear over the long term.

And this is where the problem lies: There’s no obvious solution. “Change might come from legislation, or collective action, or continued feminist advocacy, but it’s folly to imagine it will come from companies themselves,” Peterson writes. “Our capacity to burn out and keep working is our greatest value.” But it’s hard to see how Congress could legislate the problem away, especially given that Washington is also keenly interested, for economic reasons, in having as many Americans working as possible—and doing so as efficiently as possible. As for collective action and feminist advocacy, they may help improve employment at the edges, but it’s worth noting that even 9-to-5 workers with generous vacation time can burn out.

It may be impossible to eliminate burnout altogether. As long as we toil, there will be pain. But we can surely ease it. Burnout arises in our organizations, but it’s a product of the unhealthy interpersonal relations we have there. That means it’s not fundamentally an economic or political problem. It’s an ethical one. It stems from the demands we place on others, the recognition we fail to give, the discord between our words and actions. The question can’t just be how I can prevent my burnout; it has to be how I can prevent yours. The answer will entail not just creating better workplaces, but also becoming better people.

Every so often a book comes along and changes the way you see a classic of literature. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, published between 1977 and 1984, came out decades after Woolf’s death in 1941, and added a stunning lens through which to view her long and dynamic career. Her husband Leonard had carefully edited a volume initially in 1953, one that focused entirely on Woolf’s writing process and avoided personal details, but it was only when Woolf’s diaries were released in their totality that readers gained a precious glimpse inside a complicated mind at work.

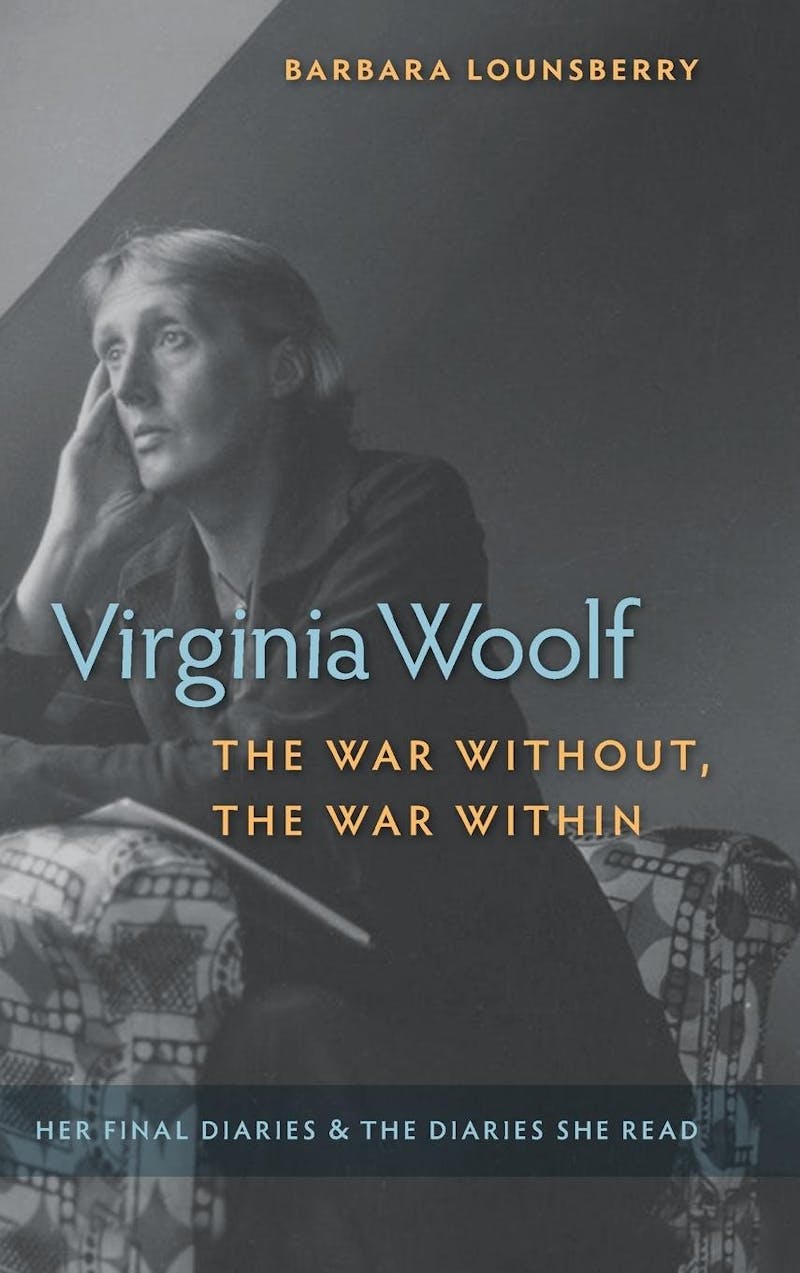

VIRGINIA WOOLF, THE WAR WITHOUT, THE WAR WITHIN: HER FINAL DIARIES AND THE DIARIES SHE READ by Barbara LounsberryUniversity Press of Florida, 408 pp., $84.95

VIRGINIA WOOLF, THE WAR WITHOUT, THE WAR WITHIN: HER FINAL DIARIES AND THE DIARIES SHE READ by Barbara LounsberryUniversity Press of Florida, 408 pp., $84.95They revealed a Woolf unexpectedly playful and at times mundane: “So now I have assembled my facts,” she wrote on August 22, 1922, “to which I now add my spending 10/6 on photographs, which we developed in my dress cupboard last night; & they are all failures. Compliments, clothes, building, photography—it is for these reasons that I cannot write Mrs Dalloway.” They also reveal a Woolf at times both vicious and shitty: her cattiness, her casual racism. Ruth Gruber, who wrote the first PhD dissertation on Woolf, had a short, pleasant correspondence with her in the 1930s, only to discover, when the diaries were later published, Woolf referring to her dismissively as a “German Jewess” (Gruber was born in Brooklyn). As Gruber would write of the experience, “Diaries can rip the masks from their creators.”

Unlike many writers’ diaries, The Diary of Virginia Woolf has become more than just a gloss on her novels; it is a work of literature in and of itself, a powerful and startling look into the inner life of a woman writer during a dramatic time. “I will not be ‘famous,’ ‘great,’” she wrote in 1933. “I will go on adventuring, changing, opening my mind and my eyes, refusing to be stamped and stereotyped. The thing is to free one’s self: to let it find its dimensions, not be impeded.” Woolf began writing in a diary in 1897, when she was just 14 years old; she would continue on and off again, for the rest of her life; she would write the final entry four days before her death in March 1941. In total, she wrote over 770,000 words in her diaries alone.

“Woolf’s semiprivate diaries serve as the interface between her unconscious and her public prose,” writes Woolf scholar Barbara Lounsberry, an emeritus English professor at Northern Iowa University. Now, over the course of three books, Lounsberry has provided a key to understanding that diary more fully: what it is, how it was made, and how to read it. In Becoming Virginia Woolf: Her Early Diaries and the Diaries She Read (2014), Virginia Woolf’s Modernist Path: Her Middle Diaries and the Diaries She Read (2016), and now Virginia Woolf, the War Without, the War Within: Her Final Diaries and the Diaries She Read, Lounsberry offers a comprehensive and thorough reading of The Diary of Virginia Woolf and, in the process, has changed how it should be read.

Lounsberry’s reinterpretation starts with the title itself: There is not a diary of Virginia Woolf, but 38 different journals and diaries. Each volume is its own book, each a discrete project started by Woolf with a different purpose and at a different moment in her writing career. This difference is essential. Read as a single, long work, Woolf’s diary might resemble Joyce’s Ulysses or Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu: something grand, monolithic, and almost over-bearing, the creation of a holistic and unified author of canonical masterworks. But Woolf, like all of us, was not a single person so much as a cascade of different voices, emotions, personas—all of which complemented and conflicted with one another. By treating her diaries as she composed them—discrete but overlapping, experimental and at times provisional—we come much closer to understanding the person who wrote them.

In 1917, for example, Woolf kept two separate diaries, writing in them concurrently on several occasions. One she began on August 3, 1917, while staying at Asheham House. In this diary, Woolf focused on observations of the natural world, written in short, staccato bursts: “Men mending the wall & roof at Asheham. Will has dug up the bed in front, leaving only one dahlia. Bees in attic chim[ne]y.” This work, Lounsberry notes, “offers Woolf’s field notes for 1917 and 1918: notes of nature and notes of war. It shows her curiosity about the natural world and human labor and foregrounds the natural historian and public historian present in all her diaries but never better exposed.”

Woolf, like all of us, was not a single person so much as a cascade of different voices, emotions, personasTwo months later, she began a separate diary: a collaborative project in which Woolf and others could all record their observations. “This attempt at a diary is begun on the impulse given by the discovery in a wooden box in my cupboard of an old volume, kept in 1915, & still able to make us laugh at Walter Lamb,” she wrote on October 8. “This therefore will follow that plan—written after tea, written indiscreetly, & by the way I note here that L. [Leonard, her husband] has promised to add his page when he has something to say. His modesty is to be overcome.” These concurrent diaries, each started at a different place, each with a different aim and purpose, suggest just one of the many ways in which Woolf used the diary form to try out new voices and formal constraints, developing her voice through “a diary more structurally experimental than any of the diaries she read”—and, in the process, creating a masterpiece of interiority.

Lounsberry’s books also serve as a reader’s guide for the diaries themselves. She pays attention to the physical dimensions themselves: “This diary is too small to allow of very much prose,” Woolf complains of the diary she used in 1897, which measured 5.5 by 3.5 inches. It was exactly the kind you give to a 14-year-old girl: leather-bound, with a lock and key, a form she quickly outgrew. Later, Woolf would bind the journals herself, and in at least one prepped her work by drawing a vertical red line along the left margin of each page. Still, they often varied in size and length. “The small size of the Asheham diary,” Lounsberry notes, “may have invited compression,” referring to the rapid, clipped style that defines it.

The other major thread through these books is not just the diary Woolf wrote, but the diaries she read: Lounsberry keeps careful track of the diaries by other writers she read, and their effect on her own writing. As a teenager, Woolf devoured Samuel Pepys’s 1.25 million word diary in twelve days; Pepys, along with Fanny Burney, Walter Scott, and James Boswell, would be a major influence in Woolf’s own diary writing; and throughout her writing career she would constantly borrow ideas from other diarists. From Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, for example, Woolf got the idea “to experiment and to collaborate” with a diary, leading to the Hogarth House diary with its multiple authors. She was, Lounsberry contends, “more steeped in diary literature than any other well-known diarist—and likely even since.”

We are used to literary works responding to one another: Ulysses rewrites The Odyssey, Wide Sargasso Sea imagines a story adjacent to Jane Eyre. But these are published works speaking to other published works. Woolf’s dialogue with other diarists is different. A diary is a private monologue by one writer, made public posthumously (in Pepys’s case, centuries after it was written), and Woolf is responding in turn in her own private setting.

Never, though, entirely private. Even from a young age, Woolf seems to know her diaries may someday be read by others: “I have made the most heroic resolution to change my ideas of calligraphy in conformance with those of my family,” she writes in 1899, recognizing even then that she wants her private thoughts to someday be read by others. She also reread her own diaries, a process Lounsberry charts throughout all three books, one that further enriches them as “she constantly rereads it with a critical and curious eye.”

Traditionally, Woolf’s diaries have been divided in half. There are her mature diaries, comprised of the five volumes that were published between 1977 and 1984. These begin with 1915, the year her first book, The Voyage Out was published, as though to emphasize that they are the thoughts of a published writer, and not just some unknown young girl. Those earlier diaries eventually appeared, in a far more edited form, in 1990, in a volume titled Passionate Apprentice. Lounsberry rejects this split for a tripartite structure: Her first book focuses on her early, experimental diaries, through 1918; the second, the diaries of her high modernist years (through 1929); and the third, the diaries of her final decade, when she struggled with her final masterpieces The Years, Three Guineas and Between the Acts, while trying to ward off depression as the world collapsed with the march of fascism.

Lounsberry’s first volume is perhaps the most interesting, when Woolf is most actively experimenting with what a diary is and can be. Woolf’s first two novels, The Voyage Out and Night and Day, are both accomplished, but relatively unadventurous, formally speaking, opting for generic conventions of the nineteenth-century realist novel. It wouldn’t be until 1922’s Jacob’s Room that she would begin radically experimenting with what the novel could be. But with her diaries, by contrast, she had already been radically experimenting for decades, trying out new forms, incorporating what she was learning from Pepys and Boswell and turning these lessons to new ends.

The middle years, the years of Woolf’s greatest successes, when writing came fastest to her, correspond with her leanest diary years—as long as she could effortlessly turn writing into paid work and novels, she had less need for a private well of secret thoughts. Her “Spare, second diary stage” is perhaps the least revealing of the three, for the simple reason that much of her best writing went into her 1920s masterpieces: Mrs. Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, A Room of One’s Own, and Orlando (along with A Common Reader and the flood of essays and other work from this period).

By the third volume, Woolf’s creative process is running aground: The Waves, despite its brilliance, doesn’t come easily, and the stubborn 1937 novel The Years nearly defeats her altogether. More and more, she turns to her diary to write free of the constraints that her public persona has foisted on her. (“Oh what a grind it is embodying all these ideas, she writes on March 18,1935, “& having perpetually to expose my mind, opened & intensified as it is by the heat of creation to the blasts of the outer world.”) In these years, Lounsberry suggests, a battle “plays out across Woolf’s diaries: her fierce fight for freedom.”

In the late diaries, what’s left out is as important as what’s written down. Woolf’s nephew Julian Bell left to fight in the Spanish Civil War on June 7, 1937; Woolf learned of his death on July 20. For the next two weeks, Woolf doesn’t touch her diary; finally, 17 days after news of his death, she writes, “Well but one must make a beginning. Its [sic] odd that I can hardly bring myself, with all my verbosity—the expression mania which is inborn in me—to say anything about Julian’s death.” If these private diaries once offered her a way to put her secret thoughts into words, by the late 1930s these thoughts are now beyond words. Increasingly, these lacunae define her late diaries, as the war and her own internal demons overtake her.

Lounsberry’s books are methodical, at times plodding, working forward chronologically through each diary, interspersed with whatever diary Woolf was reading at the time. At times it feels more archival than anything else. Her target audience is primarily other Woolf scholars, of course, but there’s something here for all fans of Woolf’s diaries, as well as anyone interested in how a woman writer navigates the role of public and private writing. As modernist scholar Elizabeth Podnieks argues, “many women wrote their diaries by keeping up a pretense that they were private, while intending them to be published at a later date. In this way they could communicate to an audience thoughts and feelings that were too personal or controversial to be revealed through their fiction, but which they wanted, and needed, to convey.” Woolf is an almost paradigmatic example of this, offering a variety of catty, quotidian, and sometimes mean-spirited selves that contradict the image formed by her carefully-sculpted works. Rather than treat the diaries solely as the behind-the-scenes key to the novels, these books instead chronicle the push and pull of her private and public writing, offering a fuller picture of Woolf’s life.

With luck, they’ll also spur a longer conversation about reevaluating Woolf’s diaries. And perhaps—U.S. and U.K. copyright laws notwithstanding—we might see stand-alone editions in the future: the Asheham Natural History Diary, the Cornwall Diary of 1905, the sketchbook of 1903. Barbara Lounsberry has done for Woolf’s diaries what the diaries once did for Woolf’s novels, and what all great literary criticism seeks to do: It takes a canonical work of literature and offers an entirely new way of seeing it.

No comments :

Post a Comment