I didn’t expect, when I first moved to South Africa in 2009, how much it would feel like America. Every place does, more and more; or every place feels increasingly like every other place, a globe of placelessness, the world as duty-free lounge. But South Africa was even more so. It was as if the geographical strata of American society—gentrified urban, marginalized urban, suburban, country—had been compressed into a much smaller area. Outside South Africa’s cities is cowboy country, with wide, fenced ranches punctuated by townlets featuring beef-jerky stores and tractor wholesalers. Closer in are rings of suburbs with split-level houses with pools and the occasional American-style shopping mall. The cities are divided between zones of economic despair and bourgeois-bohemian enclaves reminiscent of San Francisco or Austin.

The two countries also share a similar history. South Africa had its own (eastward) expansion by white “pioneers” in ox-wagons who set up “republics” on occupied lands. Both of their origin stories were defined by exceptionalism: America was the “city on a hill,” while South Africa’s European settlers saw themselves as chosen by God to civilize Africa’s native inhabitants. Both narratives were undermined by terrible racial prejudice. Their successful civil rights struggles led portions of both countries to feel they had overcome a substantial part of their original sin and had, perhaps, fulfilled their redemptive promise in an unexpected way.

.distance-toc { border-top: 3px solid #000; background: white; max-width: 250px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; line-height: 1.4; padding-top: 20px; } .distance-toc-header { margin-bottom: 20px; } @media screen and (min-width:640px) { .distance-toc { margin: 0 2em 2em -50px; float: left; } } .distance-toc a { text-decoration: none; text-shadow: none; } .distance-toc-info h3 { font-size: 110% !important; } .distance-toc-info h4 { font-size: 100% !important; font-weight: 500; } .distance-toc-info h5 { font-size: 90% !important; font-weight: 500; } .distance-toc-info h5 span { font-weight: 700; }

With Nelson Mandela’s ascent to the presidency in 1994, South Africa became the rare country other than the United States in which historical white power

had been substantially challenged by the rise of previously oppressed peoples of color; the only country in which whites and blacks coexisted with the latter forming a serious demographic challenge to the former; and also the only country anchored, in its identity, not on a long-defined territorial definition or on an ethnic base, but a set of ideals: tolerance, reconciliation, freedom.

There’s a conscious affinity. South Africa’s remarkable jazz was inspired by waves of African-American musicians employed on American ships that stopped in Cape Town during the late 19th and early 20th century, including the Confederate warship Alabama. (A tune whose name translates to “Here Comes the Alabama!” from Afrikaans—the Dutch-derived creole that was the main language spoken under apartheid—is still one of South Africa’s most-covered folk songs.) Its street style took inspiration from American gangster movies the apartheid authorities screened in black townships in the hopes they could get blacks to sympathize with the law-abiding sheriffs. (They couldn’t.) South Africans adore American hip-hop and country music. I once snapped a picture of a young man in Johannesburg named Madiba—Mandela’s nickname—who’d gone out clubbing in an American-flag puffer jacket. Yankees caps are hot.

The parallels, when I first arrived, had one major exception—the president. The United States was beginning Barack Obama’s first term. In South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, a figure a little like Obama—handsome, intellectual, rhetorically refined, slightly aloof—had been replaced by a far less lofty figure: Jacob Zuma.

It was a radical shift. South Africa’s first two postapartheid presidents, Mbeki and Mandela, were personally virtuous, calm-tempered international darlings. By contrast, prior to taking office, Zuma had already been accused of—and tried for—rape. (He was acquitted, although he did admit to having sex—consensual, he claimed—with a friend’s 31-year-old daughter. Zuma told the court that he protected himself from contracting HIV from her by taking a shower.) He’d become affluent through questionable means, raking in hundreds of thousands of dollars from a corrupt business adviser who sought his help to advance his company’s interests. In 2005, the adviser was put in jail, and the judge in the case publicly said the evidence was “overwhelming” that Zuma had accepted bribes. Zuma himself was charged with corruption for allegedly taking bribes from a different, foreign company.

Yet Zuma wowed crowds outside South Africa’s metropolitan centers in open-air rallies and events, sometimes dancing in traditional African clothing—a leopard-skin cape, a skirt made of pelts. He had four wives and nearly 20 children. (Polygamy is legal in South Africa, but rarely practiced by educated black men.) He played at once a strongman and a victim, calling his legal troubles a “carefully orchestrated, politically inspired and driven strategy” by elites “to exclude me.” He flaunted a belligerent streak—his signature song, an anti-white anthem from the anti-apartheid struggle, translated from Zulu as “Bring Me My Machine Gun.” He oozed a kind of authenticity missing from South African politics: rough, real, a product of spaces and cultures within the country that academics or the wealthy generally avoid.

If this sounds oddly reminiscent of the current occupant of the White House, that isn’t a coincidence. Like America, the South African story, lately, has been troubled by the sense that a group of people are languishing outside the cultural elite, harboring a growing resentment. And that these people represented the resurgence of historical tensions the country thought it had left behind. Only in South Africa, this silent majority was black.

“How much fun is it, watching the U.S. trying to deal with a President whose cronies are guilty of crimes—involving him—while he still holds office?” a South African tweeted recently. “Feels a bit like watching someone else have your nightmare: a little nostalgic, a little scary, a little superior.”

He oozed a kind of authenticity missing from South African politics: rough, real, a product of spaces and cultures within the country that academics or the wealthy generally avoid.

Superior because South Africans got rid of their Trump. Eventually, a combination of factors worked against Zuma: relentless investigative work into his activities by the country’s top journalists; a big electoral loss for the ruling ANC party in municipal elections in 2016; elite outcry at his excesses; and hard pushback by the country’s judiciary institutions. In a late-night address last February, Zuma resigned as the country’s president.

Sometimes I like to tell people back home that South Africa collapses 200 years of American history into just two decades: our past—in substantial ways South Africa before 1994 resembled the antebellum South—and our future, insofar as a white-run, purportedly white-designed, and visibly white-dominated public space is now dominated by people of color.

Maybe South Africa has something to teach America: how to react to a leader like Zuma, one whose hard break from the political status quo yielded outrages

and disregard for the truth that seemed to amplify with each passing day. And what can happen when a society gets rid of such a man. It’s hard to look past the presidency of a person like Zuma or Donald Trump, hard to focus on anything but his survival or his downfall. But South Africa has been past it for almost a year now. “Twenty-one years into our democracy, we are facing a crisis that could render our society dysfunctional,” Stephen Grootes, one of the country’s top political commentators, wrote of Zuma in 2015. Eventually Zuma was brought down. Had democracy been saved?

Mothakge Makwela, an early Zuma supporter, believed Mandela and the ANC didn’t do enough for blacks at the end of apartheid. “We are suffering now because of the deal they agreed to.”

Mothakge Makwela, an early Zuma supporter, believed Mandela and the ANC didn’t do enough for blacks at the end of apartheid. “We are suffering now because of the deal they agreed to.”The township of Diepsloot—“deep ditch” in Afrikaans—is a relatively new settlement, a few square miles of poor, almost exclusively black people who have been coming to Johannesburg since the restrictions on movement that confined many blacks were lifted in the early ’90s. Diepsloot is a bellwether for events in postapartheid South Africa. Before I moved to the country, I’d read books on the magical redemption story that was its peaceful transition from white- to black-majority rule. I’d seen the photographs of Mandela triumphantly clasping the hand of the country’s last white president, an iconic end-of-20th-century symbol of humanity’s potential to overcome the darker, prejudiced aspects of its nature.

Yet there was also the strong sense something was off. A feeling hung over the country that some national center couldn’t hold. Inequality had increased since the end of apartheid, as some well-positioned people—whites with capital and well-connected people of color—were able to take advantage of the end of apartheid-era sanctions and market their wine or banks or clothing companies or sheer coolness throughout Africa and the world. White-headed households still brought in five times the income of black-headed ones. “Madam,” a black child politely asked me once while I was taking a stroll in a Johannesburg neighborhood, “why aren’t you in your car?” He had never seen a white woman on foot before.

Diepsloot was presented in the media as the epicenter of the problem. Hardly a week went by without a hair-raising story of violent protests against bad plumbing and attacks against migrants from elsewhere in Africa, on whom the residents took out their rage. Anton Harber, a leading journalist, warned that “if you want to understand where this country is headed, listen to the people of Diepsloot.”

On a recent afternoon I drove there to do just that. Mansions stood atop peaks lit gold in the waning sun, and sweet wooden signs swung along the main road: PARADISE BEND, COPPERLEAF GOLF ESTATE. The region around Diepsloot is colloquially considered “horse country,” a pastoral swath of homesteads and farms between Johannesburg and Pretoria, the country’s capital. It looked on Google Maps as if I were right on top of Diepsloot, but I couldn’t see or hear it.

Yet there was also the strong sense something was off. A feeling hung over the country that some national center couldn’t hold. Inequality had increased since the end of apartheid.

A quirk of South Africa’s geography is that it makes starkly, physically real the kinds of cleavages that, in other countries, tend to be more figurative. Under apartheid, white-only neighborhoods were often intentionally separated from black, Indian, or mixed-race neighborhoods by a physical feature, like a river or a railway line. Townships were nestled into dips in the land, tucked behind the prettiest face of a mountain; some were even hidden in acoustically enclosed areas. From many a balcony or front stoop, South Africa still preserves the fantasy that life can be led as if black people don’t exist. Much of the country remains enveloped in an eerie quiet: a silence so profound you can hear the lourie birds calling or the beating of your own heart, even though you know, very close, there are thousands of other hearts, beating, invisibly.

I finally followed a pickup truck around a bend—the area around Diepsloot is undergoing development, and the back of the truck was filled with black construction workers—and there it was: a single shopping mall, with a rectangle of banks and a Kentucky Fried Chicken, and block upon block of shacks and street-side stalls selling shoes dumped by American charities and grilled chicken feet.

I had come to Diepsloot to meet a 36-year-old resident named Mothakge Makwela. I’d met Mothakge seven years earlier when I’d followed the journalist Harber’s advice and paid my first visit to Diepsloot. Mothakge operated a web site with articles dedicated to giving outsiders a view of township life.

This time, though, I wanted to talk to him about Zuma. Mothakge had been a huge Zuma supporter, organizing for his first election campaign in Diepsloot. “He was for the ordinary folk,” Mothakge said.

A slight man with short dreadlocks and soft eyes, he wore noticeably pressed clothes—best to be disarmingly nice and reassuringly gentle-spoken to receive visitors. We went to the KFC at the Diepsloot Mall to talk about his past, and for him to explain to me how he could have supported a man like Jacob Zuma. As we ordered, the cashier entreated us to “add hope” to our bill for two rand (about 15 cents)—a campaign for a charity. Mothakge laughed and said that mirrored his experience coming of age in postapartheid South Africa. “Hope,” he said, “was always something you buy.”

Born in the country’s rural east and raised, in part, in Diepsloot, Mothakge was 11 when Mandela was inaugurated. The thrill around the transition to democracy had led him to expect something entirely different for himself than his parents had gotten out of life—his mother was a maid, his father a driving instructor. And he’d done his part, excelling in South Africa’s famously difficult high school exit exam. He’d hoped to become an engineer and to live in a place like Ferndale, the lush Johannesburg suburb where he’d spent two years of high school on a scholarship.

But when he returned to Diepsloot after graduating, he began to feel he and his friends “were actually getting poorer.” He could never make enough money to live in the central neighborhoods where whites still lived and operated businesses, while “so-called investors” who came to Diepsloot promising benefits—like the mall with the KFC—took out most of the cash, giving little back to the community. The new black leaders seemed to neglect the township, regarding it as an embarrassment and chastising the black people there “for the dirty way we lived” and for attacking foreigners.

Thabo Mbeki—a British-educated dandy who liked to quote Latin—had frequently left the country to hang out at Davos and had instituted an affirmative-action program that ended up mainly benefiting the well-connected. Mothakge peeked into those beneficiaries’ gilded lives when he and his friends would walk to the Fourways Mall in Johannesburg—one of a host of fancy new developments that were springing up in formerly white neighborhoods. It boasted a specialty surfwear boutique, diamond jewelry stores, Steve Madden and Nike shops, and a gourmet frozen yogurt stand. Shop owners and staff would follow Mothakge around, he said, assuming that he was a thief. “When you actually pay, you can see how relieved they are,” Mothakge said bitterly. “And this was done by our black brothers and sisters.”

Mothakge was especially upset by the wide-open spaces he saw when he walked. So much land surrounded the cramped township: undeveloped fields being held by property companies as investments, fenced with razor wire, overhung by tall, black spotlights, and posted with signs warning that “trespassers”—people like himself, he gathered—would be arrested.

He could not understand why, after apartheid, he would be called a “trespasser” in the eyes of a police force run by a black president. “This is my land now,” he said. But whites still owned the majority—two-thirds, by some estimates—of South Africa’s land.

Mothakge even began to doubt Mandela. After Mandela was released from prison, he’d befriended white mining and insurance magnates; in the late 2000s, before Zuma became president, an interpretation circled around Diepsloot that the deal Mandela and the ANC had negotiated for black people had been a Nobel Peace Prize-friendly abrogation of justice that had left apartheid’s brutally unequal economic system—and the racism and classism that enabled it—intact. Economic experts and the black leadership always insisted nothing really radical could be done about apartheid’s legacy; if a redistribution was attempted, the country would undergo a postcolonial collapse, like Zimbabwe next door. “We are suffering now because of the deal they agreed to,” Mothakge told me plainly.

Like many South Africans in his position, he’d put his hopes in Zuma. One of the interesting things about Zuma is that a wider range of people initially supported him in South Africa than backed Trump in America. A white friend of mine, a young entrepreneur, posted “100% ZULU BOY”—one of Zuma’s slogans—on his Facebook wall. Another friend—a bowtied white executive—rhapsodized to me about Zuma’s multiple wives. He mentioned a newspaper photo he’d seen of three of them asleep together on a bench, beatific looks on their faces, and expressed awe that “one man” could keep that many women “so happy.”

If some of Trump’s support in America reflected a reaction to genuine problems—governmental gridlock, economic anxiety, the sense that elite wisdom no longer spoke to many Americans—in South Africa, the problems that gave rise to Zuma were considered even more critical to resolve. Crime, fed by inequality, had ballooned to the point that some analysts designated the country perhaps the most violent in the world. My friend who posted “100% ZULU BOY” said he felt relieved that the face of leadership might be shifting away from people who looked, or at least acted, so much like him; the tone and priorities of political leaders had just seemed wrong, since most South African voters were not well-connected and polished like Mbeki. And it had seemed dangerous. “There is a rage building at the base of society,” a university professor warned during a lecture I attended. “That rage has the risk of burning everything we have built in this country over the last 15 years.”

Mandela and Mbeki had often used words like “prudent” and “modern” to justify their leadership style. As the heads of the last African country to overthrow white rule, they harbored an intense fear of becoming another sad postcolonial tale. They didn’t want to do anything Marxist or pan-Africanist or against the received wisdom of international experts, financiers, or the people who already held capital. The African postcolonial narrative most foreign observers—and investors—knew was that even well-intentioned leaders who broke with Western advice, like Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Mozambique’s Samora Machel, ruined their countries. By the late 20th century, South Africa was by far the richest African country. It carried on its shoulders the pride and stability of a continent. It had a reputation to sustain.

But their fastidious efforts to act like “acceptable,” upstanding Western leaders led them, even if unwittingly, to perpetuate political habits ingrained during white rule—favoring the interests of the already-wealthy, spouting high-flown language about principles that resulted in too little for the country’s poorest. “I feel like a lot of the leaders we have—you liken them to white men in society,” Tshidi Madia, a black journalist, told me. “Where they become so removed from the people they serve. There is absolutely no shame in jumping out of a Range Rover into somebody’s shack and saying, ‘Hi, I stand with you!’” Elite skepticism of Zuma reminded Mothakge, painfully, of the suspicious way he was viewed at Fourways Mall.

Zuma might have been “corrupt,” but he spoke to a deeper truth underlying South African life, which was that it was entirely rational to question what publicly presented itself as respectability and virtue. S’thembile Cele, another journalist, told me something that sounded paradoxical, but that makes sense—and which parallels the feeling many of Trump’s supporters have about him. “Zuma was untainted by false goodness.”

Fighting Zuma’s corruption made people like journalist Tshidi Madia more cynical, a shift in attitude that lasted past his ouster.

Fighting Zuma’s corruption made people like journalist Tshidi Madia more cynical, a shift in attitude that lasted past his ouster.It was almost eerie how short Zuma’s honeymoon period was. Once he got into power, there was a near-instant recoil from some of the behaviors people had looked forward to, or at least condoned, when Zuma was just an alternative to the status quo. With government money, Zuma began expanding a large homestead in his home province. This befit a Zulu chief, but taxpayers complained. He attacked a white cartoonist for lampooning him; prior to his election, it might have been enjoyable to see him thumbing his nose at a white journalist’s notions of propriety, but once he held office it provoked outrage. Instead of appointing fresh figures as his Cabinet ministers, he tapped cronies late at night and, like Trump, swapped them out constantly.

It soon became clear Zuma’s crookedness was not revolutionary nor symbolic. The ground didn’t quake with change, or even plain old vengeance against the unjust system; instead, he seems to have just stolen a lot of money, pilfering from various state agencies, and then retreated out of sight and sired more children with several other women. Many bad things happened and almost no discernibly good things. Inequality climbed while the rand devalued by more than half against the dollar; his associates got rich while prosperity slipped further out of sight for the likes of Mothakge Makwela. “The African son of a working-class family let down the country,” is how Mothakge put it that afternoon at KFC.

These accumulating outrages united the country for the first time, perhaps, since Mandela’s election. South Africans came to share a refreshing sense of enmity to Zuma. It seemed as if every political commentator put out a book ascribing South Africa’s dysfunctions—from its power outages to its corruption—to Zuma. Every problem became associated with him: “If the rand fell, it was Zuma,” Mothakge said. “If it rained, it was Zuma.” Civil-society groups filed reams of cases against him.

South Africa has an entity like America’s special prosecutor, but standing, not appointed on a case-by-case basis. The Public Protector, Thuli Madonsela, prepared a dossier over years on Zuma’s malfeasance, and it became the hope on which the country hung. As we now have Robert Mueller versus Trump, they had the public protector versus Zuma. One news outlet dubbed Madonsela the “guardian” of “what is good and great about South Africa.”

In a hipster café in downtown Johannesburg where I ate a couple of days after I met with Mothakge, I saw a copy of The Economist from October 2016 prominently displayed on a table near the front window. “Healthy democracies depend on unwritten rules,” the lead editorial—on Trump—stated.

I suspected the magazine was there because its opinion seemed to speak to the mood in South Africa, too. The discomforts with the status quo that had swept Zuma into office had been temporarily forgotten, replaced by a hearty defense of institutions and political norms. People now felt that their traditions and norms were precious, and Zuma had violated them. It was strange, though, because this sentiment was nearly the opposite of the one that had dominated the country a decade earlier. A reminder of the former mindset lay tucked beneath The Economist in an obscure foundation’s 2016 report on economic inequality—an injustice propped up, in South Africa, by the kind of unwritten societal rules the populace was going to the barricades to defend. “An exhausted woman working 60 hours a week in a clothing factory,” it read. “A woman cleaning luxury gated flats at dawn, getting mugged as she walks to work from her home on the edge of the city.”

It was faded, and stained so long ago that its glossy pages had stuck together. As I labored to unglue them with a fingernail, a waiter cheerfully offered, “You can just give that to me to throw away.”

My friend Palesa Morudu, a 48-year-old black South African newspaper columnist who travels often to the United States, told me the mood in America right now reminded her eerily of South Africa in the latter stages of Zuma’s presidency—the feeling of “being at five to midnight”; “that East Coast hysteria, screaming at Trump all the time.”

But she had a warning for my fellow Americans: Even as Zuma’s adversaries imagined they were “winning,” there crept in a deep-seated exhaustion, an apathy. “What it did was make us so numb.”

South Africa accomplished what liberal Americans still only dream of—ousting their enemy. After Zuma resigned in early 2018, the ruling ANC replaced him with Cyril Ramaphosa, a much more “normal”-seeming politician and businessman highly admired by economic analysts and overseas observers. The former head of a mineworkers’ union who led strikes against apartheid in the 1980s, Ramaphosa, alongside Mandela, had negotiated the political and economic deal that eased South Africa out of white rule in the early ’90s, and many older South Africans felt a lingering affection for him. Initially, there was an outpouring of relief and excitement. People called it “Ramaphoria.”

Ramaphosa wears well-tailored suits and avoids any hint of demagoguery, speaking in polished, pleasing sound-bites and steering clear of rowdy Zuma-style mass rallies and the press. He nonetheless took office with a history arguably as damning as any postapartheid leader. Extraordinarily wealthy, he serves on numerous boards. In 2012, he emailed the board of a platinum mine on which he serves to encourage them to deploy the police against a group of desperately poor miners striking for higher wages, calling them “criminal.” The next day, the police shot 34 miners dead in South Africa’s worst massacre since apartheid’s end.

Nothing could have been more symbolic of exactly what had disturbed South Africans back in the 2000s about the trajectory of their politics: that leaders who’d once represented the people had become their adversaries; that power brokers were using fully legitimate channels and nice-sounding language to achieve unjust ends; that evildoers draped themselves carefully in the globally recognized apparel and rhetoric of virtue.

A friend told me the mood in America right now reminded her eerily of South Africa in the latter stages of Zuma’s presidency—the feeling of “being at five to midnight”; “that East Coast hysteria, screaming at Trump all the time.”

In a way, the feelings that pervaded South Africa when I arrived ten years ago resemble America’s sense of itself before Trump. It’s easy to hate Trump’s behavior now. But we can’t deny that, for decades before his rise, a wide range of Americans wanted something loosely like it. Liberals would have been thrilled to have a president a little like Trump—uncompromising, willing to call political adversaries out as hypocrites—if she or he had pursued liberal policies.

As in South Africa, myths we’ve long been telling ourselves about our country have been coming apart—that we’re united, that we’re fair, that the people who attain power and respectability in our society are, thanks to our values, likely to be good people.

Much like South Africa after its liberation, the United States surged into the 1990s in a triumphal mood. Francis Fukuyama wrote, “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War ... but the end of history as such,” a time when “all prior contradictions are resolved and all human needs are satisfied.” Bill Clinton assured us that free trade would benefit all Americans. Economists and web designers talked of the coming of a technocratic utopia. “Equality between the sexes,” proclaimed one op-ed in The New York Times, had been “accomplished,” and in high school, my friends and I learned that racism was obsolete. America was so confident, outwardly, it invaded Iraq presuming it could redesign it from scratch with a 24-year-old Yale grad at the head of its stock exchange.

But all was not actually well. The contradictions of modern American democracy we’d tried to convince ourselves had been vanquished—racism, sexism, Gilded Age-style consumerist excess, the merging of the political class with the economic elite, hubris abroad—remained entrenched. The same year Clinton won the presidency, Los Angeles exploded in violence after the police beat Rodney King. After an affair, Clinton was impeached with great moral righteousness by men who were secretly conducting their own affairs, and he was succeeded as president by a so-called conservative who sank $2 trillion of his taxpayers’ money into a failed Middle East redecorating project. An opioid epidemic began to take root in areas devastated by the venture-capitalization of American business, the disappearance of manufacturing, and still-simmering racial tensions.

By the late 2000s and the Great Recession, it was clear that many of the things we were told by the people we were expected to trust might not be true. Trust in government fell dramatically—and not just trust in government, but trust in doctors and journalists and academics and every kind of arbiter of political and societal norms. And it was deserved. Financiers escaped consequences for the recession. The media helped lead America into the Iraq War. Political discourse itself seemed, more than ever, to be built on a foundation of utter bullshit. Self-described “conservatives” blew up the deficit while a “liberal” president bailed out robber barons. We wanted change. Radical change. Remember that?

After ousting their new president, South Africans turned back to the kind of leader they had felt so bitter about a decade ago. But unlike Zuma, Ramaphosa didn’t make a show of his corruption. His closest political ally is the now-deputy president, a former provincial governor so sleazy he’s been credibly accused of stealing money meant for poor schools and faces questions about his role in political assassinations. But Ramaphosa takes care not to appear in public with his consigliere too often. At least, the journalist Tshidi Madia told me, Ramaphosa “keeps it”—his corruption—“quiet.”

As in South Africa, long-held myths about our country have been coming apart—that we’re united, that we’re fair, that the people who attain power and respectability in our society are, thanks to our values, likely to be good people.

It was as if the South Africans who fought against Zuma had subtly shifted their goalpost from a wish for truly new leadership to a lesser, more cynical ambition: to have leaders that simply had the decency to conceal their wrongdoing. “I wanted Ramaphosa to win,” my friend Palesa told me. “I just wanted to breathe a little bit. Do you know what I mean? Is our president self-interested, or a traitor? Neither is good, but I started to feel one was a little better.” Madia told me that because South Africans’ aspirations—for more economic justice, for less racism, for less worship of a far-off Western standard of leadership and life—had become associated with such a tainted vehicle, Zuma, these deeper yearnings for change became “a bit discredited.” If a more “authentic” president had been such a nightmare, maybe more authenticity itself was not worth aiming for.

Zuma had been a nearly unmitigated disaster. But the things some people had hoped he would do—such as rejecting the old elites’ kowtowing to the Davos crowd, fighting the political class’s deepening hypocrisy, telling hard but refreshing truths, enacting more economically redistributive policies—hadn’t been silly or wrong. They were necessary. They remain necessary. But the interesting thing—and remember my friend Palesa’s numbness—is people are no longer as convinced that they are. In the course of the fight against Zuma, South Africans’ commitment to certain important democratic institutions that he attacked, like the judiciary, deepened. But other, crucial commitments—such as the conviction that a healthy democracy should provide fair opportunities for all, and that politicians should be expected to do some actual good—were weakened. South Africans thought they had won, but in some sense, they had also been defeated.

After Zuma, Tshidi Madia, once an ardent idealist, radically shifted her expectations for her country. She seemed to have accepted that its politics—that its society—was profoundly corrupted. She showed me some pictures she had on her phone of Ramaphosa’s ally, the one who allegedly arranged hits on his political opponents. She had met him a few times and thought he was cute.

“I adore him,” she confessed. “They call him ‘The Cat,’ since he’s sly. We get along really well!” She laughed shyly. “He has the most beautiful smile. I can’t believe I’m saying that.”

She recognized that there was something sad about rewarding just-barely-less-bad-than-Jacob Zuma as virtue. But South Africans were so burnt out by the existential fight they pitched against Zuma, and so desperate to see the leader who came after him as good, that they blinded themselves to Ramaphosa’s iniquity. Ramaphosa’s behavior with the platinum mine was disturbing, she said, but “nobody wants to hear about it. South Africans want to have a head of state they think they can believe in.”

Zuma’s failures changed South Africans’ political expectations. “So, Ramaphosa is the friend of the white people,” said Armstrong Nombaba. “Is it wrong?”

Zuma’s failures changed South Africans’ political expectations. “So, Ramaphosa is the friend of the white people,” said Armstrong Nombaba. “Is it wrong?”It’s hard to imagine, right now, that America could become more cynical after Donald Trump’s departure from the Oval Office. An assumption underlies the ferocity of the left’s resistance to Trump—that it would be deeply meaningful to defeat him, a sign that America still has some humanity and virtue left in her.

But in South Africa it has turned out somewhat the opposite. In the course of their battle, Zuma’s adversaries found themselves defending some of the very institutions—the press, academic economics, “politics as usual,” and the whole language with which the country described itself and its moral framework—that they had recognized, prior to his presidency, were badly compromised. In the process, a renewed, slightly bizarre aura of righteousness settled around certain political norms, traditions, and institutions that hadn’t been so great, but briefly looked that way. South Africans concerned with public virtue staunchly defended the media despite its enduring sloppiness, pomposity, and obsession with shock value. They lauded elite prognostications despite their racism and classism. They touted the value of “political norms” despite these norms’ historic tendency to reward smooth-speaking crooks who did very little for their constituents. It wasn’t so easy, after Zuma fell, just to revert to their former zeal for something different.

An assumption underlies the ferocity of the left’s resistance to Trump—that it would be deeply meaningful to defeat him, a sign that America still has some humanity and virtue left in her.

Many Americans have also found themselves attacking Trump for things that, before his rise, they had wanted. Like abandoning outdated alliances and forging new ones. (Eighteen years ago, The New York Times editorialized in favor of “a closer engagement” with Russia and Putin.) Like bucking norms, and even laws, that no longer serve truth and justice. (As Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning did.) Like jettisoning politeness and protocol and strong-arming Congress to achieve effects. (“There is something in the modern Democrat that abhors the raw exercise of power as a little bit, I don’t know, vulgar,” Timothy Noah complained in the NEW REPUBLIC in 2012, calling for a less accommodating approach.)

People who suggest that the Trump phenomenon has been driven, at least in part, by dissatisfactions that even the people who hate him share are pilloried. But it’s true: We’ve all felt fury at how America parades around with self-righteous armies in foreign lands while neglecting problems at home. We’ve all hated the way elites sunnily press aspects of globalization that turn out to benefit only themselves. We’ve all felt bitterness toward “experts” who claim their opinions are the only possible truths, lead millions to ruin, and dance away unharmed. We’ve all grown disillusioned with a media that insists it be treated as a kind of oracle, blameless and objective, while concealing its inevitable biases, its susceptibility to the pressures of advertisers and trendiness. We’re all tired of politicians who spout an increasingly indistinguishable stream of pabulum, never doing anything—well, vulgar. All of these problems have been figurative Diepsloots for America for a while now, dangers that we try to hide from our view, but we always know are there.

The way Trump has addressed these dissatisfactions may not be, to put it mildly, to everybody’s taste. Like Jacob Zuma, he is in all probability a dangerous criminal. But Palesa told me she now regretted, somewhat, the single-mindedness of her opposition to Jacob Zuma, instead of focusing on the country’s broader social and political problems. Some of the hopes Zuma initially appeared to embody are still, in fact, legitimate, though it now feels clear his intentions were never good, she said. She wished South Africa had realized that Zuma might not be the only—nor even, long term, the worst—threat to South Africa.

Trump is so triggering to so many Americans that it’s nearly impossible to simply say tone it down to his adversaries, but Palesa implied that it was necessary. “It took all my energy,” she said of battling Zuma. Afterward, she had so little left, even though his ouster left so many problems unresolved.

Madia agreed. “We don’t really believe inequality will be resolved anymore,” she told me. In her reporting, she still visited “the poorest of the poor, and heard the most heartbreaking stories. But sometimes I get the sense that they, too, know now there might not be an answer.” I see America rallying around the blamelessness of institutions like the press, and I fear we might regret what dissatisfactions and skepticisms and hungers for difference we might drive from ourselves as we try to drive Donald Trump from our politics. All the anti-Trump defenses of “norms” in America startled Palesa. In South Africa and America, “norms” are as often bad as they are good. Norms kept Rosa Parks at the back of the bus.

The wholesale rejection of Trump risks, by default, ending up with a renewed commitment to the problematic status quo that generated Trump in the first place. With a resignation to something broken. Madia, the journalist, had another theory. Maybe as a society, she mused, consciously or unconsciously, South Africans had actually chosen a doomed vehicle for the correction they needed but that also terrified them—so that his failure could reassure them that such profound but unsettling change was, in fact, impossible. That they had to live with the world as it was. That there was no other alternative.

Maybe South Africans hadn’t fully wanted change, not deep down. Maybe they were more ambivalent. Maybe the chance to turn against a leader and reject all that he stood for was what they had wanted.

It’s an unsettling idea to apply to the American case, but not without resonance. The response to Trump, among his opponents, is so uniform, so violent. Madia told me that both reactions—Americans’ to Trump and South Africans’ to Zuma—reminded her of the scapegoat in traditional Jewish culture: a living goat that was heaped with symbols of the community’s sins and sent into the wilderness, as if its banishment could absolve everybody. Most traditional cultures practice some form of ritual expulsion of feared members of the community; there seems to be something human in it. The political stoning of Zuma served to confirm many South Africans’ sense of their own virtue—ironic, because his presidency had been intended to effect exactly the opposite, a communal reckoning.

After we left KFC, Mothakge and I climbed the ridge that divides Diepsloot from finer neighborhoods to its southwest. Instead of the land seizures that Mothakge had once hoped for, there was a new, gated housing development with a preposterously giant, faux-Roman aqueduct. It had been built by Douw Steyn, a billionaire white insurance broker who’d been friends with Mandela. It speaks to an increased public shamelessness in contemporary South Africa that he named it “Steyn City,” after himself. Houses there cost in the millions of dollars. There’s a golf course, a private school, and a restaurant that serves an appetizer of Falklands calamari that costs nearly a farm laborer’s whole daily wage.

The entry gate, visible from Diepsloot, looks like the Jefferson Memorial on steroids, a four-story up-lit rotunda with dancing fountains. We got in my car, drove down to the entrance, and walked around. A black security guard shooed away two young women who were trying to take photos of themselves there. The guard was happy to let me, a white person in a car, drive in alone, but he wouldn’t let in Mothakge, who was walking. “These are the rules,” he said, citing “regulations” of the estate. “I don’t make them.”

Mothakge wasn’t as upset by this as I was. Ten years ago, the pervasiveness of racism throughout South African society had helped Zuma win the presidency. It’s still pervasive, but Mothakge seemed to have accepted its permanence—even its validity. He seemed to have acquired some of the subtle contempt for black people that had previously so hurt and offended him. “Here in Diepsloot, people survive, but if you were to say, ‘Let’s go out and look for a job,’ 50 percent of the people won’t do it,” he said disdainfully.

A friend of his named Armstrong Nombaba, whom we met later, agreed. “Now the bozza”—the old apartheid word black people used for their white bosses—

“has arrived in the house,” he said, referring to Ramaphosa. “So, our president is the friend of the white people—is it wrong? A few might be saying, ‘No, you can’t trust it, he’s a friend of whites.’” This narrow-mindedness among blacks, he judged, was unintelligent. He even said he concurred with Trump’s appraisal that South Africa is a “shithole.”

Before we left Steyn City, I had the idea to take a photograph of Mothakge in front of one its high walls, looking over, to capture both what he’d said to me years ago about feeling shut out of the better world and the will he showed, then, to storm those barriers. We found one. He agreed to pose, but he was half-smiling the whole time, as if he privately thought the image was now a bit absurd.

“I want to live with white people,” he said. He chuckled wryly, but not entirely unhappily. I thought of what Madia said: that the poor now know there’s no answer. It’s sad, but a relief, too. The status quo turned out to be the devil they knew. A different world was the devil they didn’t.

“If I’m to be liberated, I must just do and be like the white people,” Mothakge said. South Africans would have to aim for the most glaringly opulent way of life for themselves—or at least pretend they could have it, or fantasize about it. He called this “the way we want to be like the Americans.”

It’s hard to find anyone who will admit to it now, but when the CenterPoint Intermodal freight terminal opened in 2002, people in Elwood, Illinois, were excited. The plan was simple: shipping containers, arriving by train from the country’s major ports, were offloaded onto trucks at the facility, then driven to warehouses scattered about the area, where they were emptied, their contents stored. From there, those products—merchandise for Wal-Mart, Target, and Home Depot—were loaded into semis, and trucked to stores all over the country. Goods in, goods out. The arrangement was supposed to produce a windfall for Elwood and its 2,200 residents, giving them access to the highly lucrative logistics and warehousing industry. “People thought it was the greatest thing,” said Delilah Legrett, an Elwood native.

In addition to bringing more containers and warehouses, the Intermodal promised to foster vital growth and development. In a town without sidewalks, grand pronouncements were made in the run-up to the Intermodal’s debut. There would soon be hotels, restaurants, a grocery store; flower shops and bars would follow. Property values would surge, schools would be flush with cash. Most importantly, there would be great, high-paying jobs, the kind that could sustain a community devastated by farm failures and the wide-scale deindustrialization of the Midwest. In Will County, of which Elwood is part, the unemployment rate soared to a high of 18 percent in the 1980s, before gradually coming closer to the national average in the 1990s. In Joliet, the nearest urban center, it hit 27 percent in 1981.

An opportunity as great as the Intermodal came with a cost. First, to help seal the deal, the town had to offer the developer, CenterPoint, a sweetener: total tax abatement for two decades, until 2022. Second, the town would have to put up with an influx of truck traffic. No matter: With large-scale manufacturing shifting to the Pacific Rim at the turn of the millennium, the warehousing and logistics industry offered a chance to get back in the good graces of a global economy that had, for decades, turned its back on rural America. Elwood yoked its hopes to warehousing, which would carry the town to the forefront of America’s new consumer economy.

In a few short years after the Intermodal opened, Elwood became the largest inland port in North America. Billions of dollars in goods flowed through the area annually. The world’s most profitable retailers flocked to this stretch of barren country, while the headline unemployment rate plunged. Wal-Mart set up three warehouses in Will County alone, including its two largest national facilities, both located in Elwood. Samsung, Target, Home Depot, IKEA, and others all moved in. Will County is now home to some 300 warehouses. A region once known for its soybeans and cornfields was boxed up with gray facilities, some as large as a million square feet, like some enormous, horizontal equivalent of a game of Tetris.

Fifteen years before Amazon’s HQ2 horserace, Elwood had won the retail lottery. “Nobody envisioned what we have out here,” said Jerry Heinrich, who sat on the board of the planning commission that first apportioned the land for development in the mid-1990s. “It was never anticipated that every major business entity would end up in the area.”

“It was never anticipated that every major business entity would end up in the area,” said Jerry Heinrich.But this corporate valhalla turned out to be hell for the community, which suffered a concentrated dose of the indignities and disappointments of late capitalism in the 21st century. Instead of abundant full-time work, a regime of partial, precarious employment set in. Temp agencies flourished, but no restaurants, hotels, or grocery stores ever came, save for the recent addition of a dollar store. Tens of thousands of semis rumbled through Will County every day, wreaking havoc on the infrastructure. And as the town of Elwood scrambled to pave its potholes, its inability to collect taxes from the facilities plunged it into more than $30 million in debt.

And that was before Big Tech rolled in. Just four years ago Amazon didn’t even have one facility in the region; now, with five fulfillment centers, it’s the county’s largest employer. Growth, once arithmetic, became exponential. Plans were made to build a new facility, this one bigger than the original Intermodal, with room for some 35 million additional square feet of industrial space.

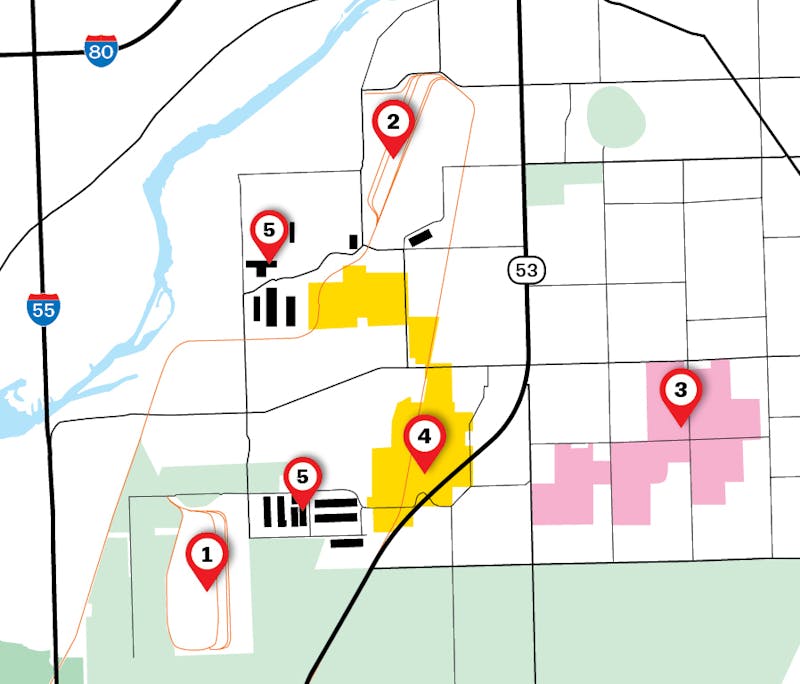

Elwood, a gateway to six major rail lines, has seen the emergence of immense warehouse projects from the country’s biggest companies.

Elwood, a gateway to six major rail lines, has seen the emergence of immense warehouse projects from the country’s biggest companies.NorthPoint, a Kansas City-based developer, began quietly buying up the necessary parcels of land. In June 2017, a map of the proposed project was leaked on Facebook. Some residents, like Legrett, saw their homes up against a new industrial park. “Some of my friends’ houses had buildings on top of them,” she said. Others fared worse. Julie Baum-Coldwater spotted her family’s farm smack in the middle of the facility. “When I saw the plan I just freaked,” she told me.

The town mobilized to stop the new warehousing development. Signs reading “Just Say No to NorthPoint” and “No More Trucks” sprouted on front lawns. Doors were knocked on. By the time the Elwood planning and zoning commission convened in December 2017 to vote on whether to recommend the facility to the town’s board for approval, tensions were high. Some 400 attendees crammed in the Elwood Village hall, with more still turned away. The meeting ran long, as did a second one, then a third, which had to be scheduled at the gymnasium at Elwood School, with bleachers packed and folding chairs on the basketball court. An overflow room with a livestream was set up in the cafeteria. Altogether, 800 people turned up, in the dead of winter, more than a third of the town’s population.

Nearly 100 speakers commented publicly; only four were in favor. Amid tears and a chorus of boos, the committee voted 3-to-1 to approve the new facility. If the people of Elwood wanted to save themselves and their town, they would have to fight for it.

In Elwood, geography is destiny. For homesteaders and farmers heading west in the 19th century, the flat terrain and quality soil made the region a major draw. “This area is kind of like a fertile crescent,” said Baum-Coldwater, whose 540-acre farm has been worked by her family for 160 years and counting. The Coldwaters are one of many multi-generational farming families in the area, producing soybean seeds, primarily, as well as corn and oats. From the front porch, they can still see the original residence Julie’s husband’s great-great-grandfather built in 1858, as well as the houses his grandmother and grandfather each grew up in, before they married.

Even the most thorough tour of Elwood doesn’t last long. The town’s nucleus sits on the west side of a highway, where a small strip mall, home to Silver Dollar restaurant and the Dollar Tree, leads to a handful of municipal buildings and a few blocks of housing. That denser development quickly gives way to a broad campestral swath, with the occasional farmhouse identifiable only because the area is so flat.

But it wasn’t topsoil that caught the eye of industry—it was Elwood’s serendipitous proximity to the country’s major infrastructure. Six class-1 railroads and four interstate highways pass through the region, which is situated a day’s drive from a full 60 percent of the country. Chicago is some 40 miles northeast as the crow flies.

For much of the 20th century, Elwood sat in the shadow of the Joliet Arsenal, an Army facility built in 1940 that churned out bombs and TNT to feed the American war machine from World War II through the Cold War. But once the Vietnam War ended, its utility subsided. In 1976, the facility was shuttered.

What to do with 23,500 idle acres became the subject of great debate. Mining and asphalt plants were suggested; a coal-fired power plant was proposed; so, too, was a new landfill. The passage of the Illinois Land Conservation Act in 1996 enshrined a solution. Nineteen thousand acres were converted into protected prairie land, where 73 head of bison currently roam. The Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery, the country’s second-largest military cemetery, was also established. That left 2,000-odd remaining acres, officially a Superfund site, too spoiled to farm. This remaining tract was zoned for light industry. For Jerry and Connie Heinrich, who headed up the effort to preserve the region’s prairies, it was the best of all possible outcomes, considering the alternatives. “The Greens were excited,” Jerry told me.

A staggering $623 billion worth of freight traversed Will County infrastructure in 2015 alone, roughly equivalent to 3.5 percent of the U.S.’s total GDP.Soon after, CenterPoint came through with its proposal for the Intermodal. The deal sounded good. CenterPoint, which is now owned by CalPers, the California public sector pension group, bought the land for an undisclosed amount. In addition to the tax abatement, Elwood, then shy of 1,700 people in total, agreed to build out a big-league water and sewer system for the facility, and extend municipal fire and police protection. In anticipation of the population and economic growth to come, they even built a new town hall, a tan, multi-story structure complete with a backyard pond and a fountain, referred to playfully as the Taj Ma-hall.

When the facility opened in 2002, it was centered around the Burlington North Santa Fe (BNSF) railroad, which subsequently bought the loading zone. Warehouses were constructed nearby. The plan proved to be an immediate success: An ambitious forecast claimed that within eight to ten years the facility would see 500,000 containers annually; that threshold was surpassed in four.

That was enough to attract the eye of a notable investor: Warren Buffett, who made a pilgrimage to little Elwood in the late 2000s to survey the facility. According to one version of local legend, Buffett took in the scene of BNSF trains unloading containers onto trucks, and the trucks casting off into all corners of the United States, and declared, “This is the future of logistics.” On November 3, 2009, Buffett bought BNSF in its entirety—and with it, the Intermodal.

After that, it was on. The success of the BNSF Intermodal, no doubt aided by the star power of Buffett, inspired railroad rival Union Pacific to set up a smaller, copycat facility across the street. The country’s richest families moved in, at least in name. In addition to two Wal-Mart warehouses, each between 1.6 million and 1.8 million square feet, Elwood got a Walton Drive, named after the Walton dynasty that owns the big-box chain.

For Delilah Legrett, a lifelong resident of the area and mother of four, the drawbacks came quickly—starting with all the trucks. Property values were supposed to skyrocket, but Legrett didn’t even feel comfortable letting her children play in front of their house with the semis hurtling through the town, sometimes as fast as 40 or 50 miles per hour. With toddlers, the persistent diesel exhaust was concerning. “We had problems with our baby monitor because it would pick up frequencies” from passing truck radios and warehouse dispatchers, she told me.

According to the Will County Center for Economic Development, at least 25,000 tractor trailers a day come through the Intermodals. That amounts to three million containers annually, carrying $65 billion worth of goods. A staggering $623 billion worth of freight traversed Will County infrastructure in 2015 alone, roughly equivalent to 3.5 percent of the U.S.’s total GDP.

“When I started, all these roads were dirt,” says Paul Buss, the 77-year-old highway commissioner of Jackson Township.

“When I started, all these roads were dirt,” says Paul Buss, the 77-year-old highway commissioner of Jackson Township.For Paul Buss, the 77-year-old highway commissioner of Jackson Township, the unincorporated land that sits to Elwood’s north, the trucks unleashed the chaos of the global supply chain on what was once a provincial post. “When I started, all these roads were dirt,” he told me as we drove around in his raised red Ford pickup. Once, a few slow tractors on the highway constituted a traffic jam. Now, the nearby interstates—the I-80 and the I-55—are swollen with semis at all hours of the day, while cataracts of trucks have spilled onto local highways and country roads. Potholes abound, and serpentine traffic jams have roiled residents. Trucks have backed over gravestones at the local cemetery after taking wrong turns. In 2016, a train derailed and hit a semi, throwing debris across the grounds of an elementary school, which was subsequently shuttered permanently for safety reasons. On the day I arrived, there were three accidents alone on I-80.

The trucks unleashed the chaos of the global supply chain on what was once a provincial post.The inconvenience of a gridlocked infrastructure pales in comparison to the horror of increasingly commonplace traffic fatalities. In recent years, a pregnant mother was killed on I-80, and an eight-year-old girl was killed off highway 53. In 2014, a truck driver fell asleep at the wheel and killed five people on I-55. After a fatal accident outside the two newest Amazon fulfillment centers, cops had to take over traffic control during the afternoon shift change. “You think it would be a big news story,” said Legrett, “but it happens all of the time.”

Buss is responsible for the country and local roads around highway 53, a ribbon of four narrow lanes that connects the interstates with Elwood. Sometimes all four lanes will be occupied by baby blue Amazon trailers featuring the company’s signature curved arrow, four immense white smiles all in momentary alignment. The facilities run 24 hours a day, and the three shift changes—morning, afternoon, and just before midnight—are particularly harried. Backups of hundreds of cars and semis are frequent. Municipalities have struggled to maintain the roads—one stretch of 53 was repaved three times last summer alone.

The turmoil has only been exacerbated by changes in the trucking industry, which has pivoted to an owner-operator model, relying on independent contractors over full-time employees. Oftentimes, truckers are paid per load—$50 to $70 to pick up a container from the Intermodal and drop it off at a warehouse. For independent contractors, responsible for their own gas and operating costs, speed is tantamount to profitability. A traffic jam can turn the trip from profit to loss. So truckers often take shortcuts down small residential roads, unequipped for weight and traffic, to shave valuable minutes off their commute. Sometimes they’ll get stuck in narrow intersections. “No Trucks” signs are ubiquitous, but they’ve been of little use as deterrents.

A map of Elwood and its environs: 1) The Centerpoint Intermodal freight terminal, operated by BSNF; 2) the Union Pacific Global IV Intermodal; 3) a proposed warehouse facility, whose size and location are based on leaked projections; 4) the town of Elwood proper; 5) warehouses.Map by Siung Tjia

A map of Elwood and its environs: 1) The Centerpoint Intermodal freight terminal, operated by BSNF; 2) the Union Pacific Global IV Intermodal; 3) a proposed warehouse facility, whose size and location are based on leaked projections; 4) the town of Elwood proper; 5) warehouses.Map by Siung Tjia“Truckers are different than they used to be,” Buss told me. “They’re just some guy off the street who bought some junk truck.” Later, we spotted a semi heading into a residential neighborhood, surging past “No Trucks” warnings. Buss flipped his lights on and sped to overtake the truck, swinging his pickup in front of it to bring it to a stop. “It’s gonna be a problem trying to get him out of here,” Buss grumbled. “There’s no training now. Most of these guys don’t know how to back up.”

Sure enough, the escape proved challenging. As the driver pulled forward to line up a three-point turn, the truck teetered dangerously on the edge of the road. Buss had to get out and wave the driver through the process. Ten minutes later, the truck finally made its exit. “It’s like this every day,” Buss said. “Every day.”

The only thing more common in Will County than the “No Trucks” signs are the hiring notices from temp agencies. The county is home to 99 in all—one of the highest concentrations of staffing agencies in the country. They share lofty, aspirational monikers, like Paramount, Accurate, and Elite. Amazon has its own preferred staffing agency: Integrity.

Temp agencies existed before the Intermodal came along—they played a crucial role in breaking the union stranglehold on labor in the Joliet Caterpillar plant. But the arrival of the logistics industry created a whole new market for temporary work. On the day I arrived, my hotel in Joliet was hosting a job fair for a staffing company called Geodis, which was looking for seasonal workers to help box Legos. After I inquired, they told me they’d be willing to hire me on the spot and start me on Monday, provided I could lift 50 pounds. They asked me to sign a 90-day contract, “temp-to-hire,” after which I’d be evaluated for a potential full-time role.

Antonio Suarez drove 45 minutes from the suburbs of Chicago for the opportunity to interview with Geodis. He was hired right away. “It seems too good to be true,” he joked nervously. Suarez told me he was expecting to work 30 hours a week for Geodis, which would complement the 30 hours he was working as a special needs caregiver. He also worked part time for his mom’s catering company, and was on his way to yet another gig delivering pizzas. He expected he would soon be brought on full-time by Geodis.

Larry Coldwater and his wife Julie are fifth-generation farmers. They worry that the diesel pollution affects their crops, and that neighboring farms will accept buyouts to make room for even more warehouses.

Larry Coldwater and his wife Julie are fifth-generation farmers. They worry that the diesel pollution affects their crops, and that neighboring farms will accept buyouts to make room for even more warehouses.While “temp-to-hire” may sound promising, the latter stage of that progression can prove elusive. A full 63 percent of the warehouse workforce in Will County is temp labor or provided by staffing agencies. At a recent hearing in Joliet to deliberate the establishment of two new companies, one group claimed that only 23 of their 147 workers had been placed in permanent full-time jobs. “And that’s their own data!” said Roberto Clack, associate director of Warehouse Workers for Justice, a Chicagoland advocacy group. “I’m not sure we believe it’s even that high.”

While Will County’s reliance on temp labor force may seem extreme, it’s part of a larger national trend. A 2016 study by Harvard and Princeton researchers dug into federal employment numbers and found that “94 percent of the net employment growth in the U.S. economy from 2005 to 2015 appears to have occurred in alternative work arrangements,” which include temp workers, on-call workers, independent contractors, and freelancers.

After I inquired, they told me they’d be willing to hire me on the spot and start me on Monday, provided I could lift 50 pounds.In Will County, alternative work is gained haphazardly and with great effort. Prospective workers use shuttle buses to skip from warehouse to warehouse because the cost of maintaining a car is often prohibitively expensive for temp laborers. (Sometimes workers will bike or walk, adding yet another element of danger to the area’s beleaguered highways.) The first shuttle from Elite Staffing in Joliet leaves at 3:45 a.m. When I first stopped by Elite, there was a line of hopeful workers out front. I was offered the chance to work that night, but denied the chance to ride on the shuttle because there were 16 people for 14 seats and those were “for the less fortunate.” A few days later, on Sunday morning, it was less crowded. The shuttle headed to the “cold stores,” a series of heavily refrigerated food preparation warehouses in nearby Bolingbrook. The first stop was Greencore, the world’s largest sandwich maker, preparing sandwiches for chains like 7-Eleven (Greencore recently agreed to sell its U.S. operations to Hearthside Food Solutions). The workers customarily don’t know if there are hours for them until they arrive, but on this day all were given a shift.

Charles Lovett worked for Elite Staffing for years, across multiple different facilities, often spreading condiments on sandwich bread or boxing A-1 steak sauce. He got into warehousing at the recommendation of his family—his aunt, cousin, and brother have all worked in warehousing. “Everyone goes in at some point,” he told me.

For those who can’t afford a car, the shuttle is a lifeline. But it can also be a burden. Sometimes, Lovett mentioned, the shuttle departed before workers had confirmed a shift, leaving them stranded at the facility for hours at a time. It was only in July that temp agencies became legally required to provide return transportation from warehouses. And though recent reforms require them to pay their workers for time spent in transit, collecting that money can be challenging. These frustrations led Lovett to finally quit. Now, he works in the Dollar Tree in Joliet, making $8.90 an hour.

Brandin McDonald, a 38-year-old African American with a stocky build and a scar under his left eye, grew up in Joliet, where he got into trouble as a kid. In ninth grade, he was thrown out of Joliet Central High School for fighting. He spent time in juvenile detention as a teenager and did two stints in jail in his twenties, disqualifying him from much full-time work. In his younger years, McDonald worked construction. But with a booming warehouse industry just down the road, he decided to try his hand at it.

The industrial expansion has not brought good jobs to Elwood. Charles Lovett, 25, was one of many to leave warehousing work after vainly seeking permanent full-time employment.

The industrial expansion has not brought good jobs to Elwood. Charles Lovett, 25, was one of many to leave warehousing work after vainly seeking permanent full-time employment.Between 2010 and 2014, he worked at the Wal-Mart facility in Elwood. There, he unloaded trucks and pallets, everything from light inventory, like artificial Christmas trees, to the unwieldy, like trampolines. That distinction was important, because McDonald, like many others, was paid not by the hour, but by the truckload. For 999 pieces unloaded, “you’d get $45, split between two people,” he told me. Small objects could be unloaded in an hour or two, but bulkier items could take three to five hours.

He hung on at the same warehouse, but his employer wasn’t Wal-Mart, historically one of the pioneers of subcontracting. As John Greuling, the CEO of the Will County Center for Economic Development, told me, “You’ll not find one Wal-Mart employee” anywhere in Elwood. The facility is run by Schneider, a third-party logistics firm, which subcontracts further, sometimes to four or five staffing agencies at a time. That arrangement has chilled any prospects of union organizing. “Under the law they’re legalized as five separate employers, you’d have to organize literally five separate companies at the same time,” Clack explained.

As one official told me, “You’ll not find one Wal-Mart employee” anywhere in Elwood.In his estimation, McDonald worked for “at least six or seven” different temp agencies during his three-plus years at Wal-Mart. Sometimes his 90-day “temp-to-hire” contracts would expire, not to be renewed, or they’d be extended repeatedly with the promise of full-time employment on the horizon. Inability to serve last-minute, mandatory overtime resulted in termination and a place on the “DNR” (Do Not Return) list. Illinois is already an “at-will” state, meaning an employee can be dismissed for any reason, without cause, at any time.

When a contract ended with one temp agency, he’d seek work from another, and get sent right back to the same warehouse, in the same role. During a stint with one particular agency, he did not receive benefits, sick days, or paid vacation for a whole year. Raises were out of the question. He drove to the warehouse every day just to find out if they had hours for him. At least he lived in Joliet: Some temp employees come from places as far as Chicago, southern Illinois, and Indiana, and can commute over an hour each direction.

With nearly 100 staffing agencies promising access to the same low-wage workforce, offering a competitive cost advantage to warehouses looking to staff up is nearly impossible. That pressure leads to corner-cutting of all sorts, which often includes wage theft, in the form of paying piece rates, skimping on hours, or having workers pay for their own drug tests, a process that was only recently outlawed. “How else are you going to cut costs?” posited Clack. “It’s this race to the bottom mentality.” McDonald ultimately filed a suit against Reliable Staffing for wage theft and won a couple thousand dollars in a settlement—but not before the agency tried to declare bankruptcy to avoid a payout. “That’s what they do,” he said, “they file bankruptcy so they don’t have to pay people.” (None of the staffing agencies contacted for this article responded to request for comment.)

Reliable eventually rebranded: It’s now called Dependable Staffing Group. McDonald now works at Wendy’s.

Elwood is now North America’s largest inland port.

Elwood is now North America’s largest inland port.All Elwood’s problems—the choking traffic, the precarious work conditions, the crumbling infrastructure—have been compounded by an original sin: the decision to forego tax collection. With little money coming in, the village issued bonds to finance the town hall, the gleaming new sidewalks, and the stop signs that are observed only voluntarily. “At the end of the day, it turns out they cut a very bad deal,” Greuling told me. “They issued bonds for a water and sewer system that was too large. They built all of this capacity and now they have this huge debt. That’s the next chapter: How are they going to find a way to retire this debt?”

Elwood, down $30 million and counting, isn’t the only town in a hole. Neighboring towns wanted a piece of the fast-burgeoning industry, and cut their own tax incentive deals with warehouse developers. Nearby Bolingbrook, where Weathertech, Ulta, and Goya Beans moved in, is now $200 million in debt. Romeoville, home to Sony and one of the county’s five Amazon facilities, is $89 million in the red. “The area grew so rapidly that we lost the ability to regulate,” said Jerry Heinrich, who continues to advocate for the region’s prairie as head of the Midewin Tallgrass Prairie Alliance, a local environmental group. “There are a lot of hard feelings,” Delilah Legrett told me. Elwood “was a small village and they were taken advantage of by a big corporation.”

The numbers are extreme, but they’re far from unusual. Despite research indicating that tax incentives rarely motivate corporate relocation, such deals are being doled out at record rates, tripling since 1990. This year, the town of Mount Pleasant, Wisconsin (population 26,000), famously borrowed hundreds of millions of dollars to help bankroll a $760 million incentive package to Foxconn, from which they wouldn’t break even for some 30 years. Smaller, but no less ridiculous, deals pervade—in 2016, a town in Maryland offered Marriott $62 million to move its headquarters just five miles down the road.

By the time NorthPoint proposed creating what could amount to a third Intermodal, one that would bring a sprawling industrial park of 30-plus warehouses spanning Elwood and the neighboring village of Manhattan, the people of Will County had had more than enough of these development schemes. The developer promised a better deal, offering to make a one-time payment to Elwood to wipe out its towering debt. (It also claimed that this facility would bring the prosperity that the previous development had failed to deliver.) But closer examination of the paperwork showed that the company would’ve made that money back over time via the generous tax structure it was hoping to secure.

Even those promises did not assuage concerns. There were suspicions that the new facility would be hooked up to a rail line, resulting in the creation of a 270-degree perimeter of development around the town. “We would be totally boxed in,” said Julie Baum-Coldwater, who began to worry that, at that point, her family farm could be targeted for eminent domain.

There were suspicions that the new facility would be hooked up to a rail line, resulting in the creation of a 270-degree perimeter of development around the town.Frustrated residents began to organize in opposition. Legrett and a group of fellow objectors, none of whom had experience in political activism, founded the group Just Say No to NorthPoint. They started small, ten people in a town hall in Jackson Township. But they quickly made their presence felt. Members showed up in the dozens at village board meetings. They printed yard signs, circulated petitions and group emails. Their Facebook group swelled to a thousand members, building an explicitly nonpartisan coalition that included both avowed progressives and MAGA-hat wearers. (Elwood overwhelmingly voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 election.)

After the planning and zoning board recommended the project to the Village of Elwood board for final approval, Just Say No to NorthPoint upped its activity. They teamed up with environmental groups like the Sierra Club and the Joliet branch of the worker advocacy group Warehouse Workers for Justice. They orchestrated demonstrations. “It was really impressive the way they built it,” said Roberto Clack, whose organization got involved with the campaign in the last 12 months.

The group put pressure on local politicians. Elwood Village President Todd Matichak, who was careful not to take too firm a position on the development, resigned days ahead of the planning and zoning meeting in December 2017, after just eight months on the job. “I guess the seat just got too hot for him,” said Jackie Traynere, a Will County Board Member from nearby Bolingbrook. The group also won the resignations of numerous pro-development Elwood board members. Finally, in April 2018, it was announced by interim President Doug Jenco that the project did not have enough votes to go through. The fallout was significant: Multiple board members left their posts, with one, who had proclaimed the NorthPoint development “a gift from God,” selling his house and leaving the area altogether.

It was a major victory. “What happened was the community organized, they resisted and they won,” Clack told me. “But there’s a round two.” Once news broke of Elwood’s refusal, the developer submitted an application with the Will County board, hoping to override local authority. Hearings will begin again sometime in 2019.

As summer turned to fall, Just Say No to NorthPoint trained their efforts on the Will County board. They organized a climate march in September, where environmental activists from as far Chicago marched alongside Elwood’s farmers to the BNSF facility, interrupting traffic in the process. The Coldwaters, who participated in the march, even sent a letter to Warren Buffett. “[T]he legacy you seek to leave behind by your generosity will, in reality, be tarnished by the personal hurt and damage done to others in the name of ‘business,’” they wrote. So far, Buffett hasn’t responded. (BNSF also declined to comment for this article.)

In early November, the city of Joliet rejected the applications for the two new staffing agencies it was considering, another small victory that would’ve seemed unthinkable a year ago. Nearby towns have begun negotiating better deals with warehouse developers. “A lot of people saw the campaign and then became empowered by it,” said Stephanie Irvine, one of the founders of Just Say No to NorthPoint.

But when it comes to the long-term prospects for the region, optimism is scarce. Paul Buss’s son, who works as a building inspector in Joliet, told his dad there’s concern “these companies are gonna come in, they’re gonna build these buildings, and they’re gonna use them for however long they can get a tax break on them, and then they’ll move someplace else.” The threat of empty warehouses looms large.

So, too, does the threat of automation. In 2017, it was estimated that 20 percent of the work in any given Amazon warehouse is automated, a figure that is expected to rise. This fall, IKEA opened up a new warehouse, 1.5 million square feet in total. “Fully automated,” John Greuling told me, it will have about 200 employees. Incredulous, I counted all the spots in the parking lot: 226.

Brandin McDonald told me he was concerned that they’d be left with a bunch of warehouses empty of people, terrible jobs having given way to no jobs at all. Legrett said she was worried about it, too. “What are all these buildings going to look like in 10 years?” she asked.

Cairo seems to be the place where American administrations declare their intentions toward the Middle East. Just shy of a decade ago, President Barack Obama stood in the city, outlining a “new beginning.” In 2005, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice had chosen a different university in the same city to present the Bush administration’s “Freedom Agenda” for the region. With age, these high-profile speeches have shown, each in their own way, that words can carry far, but must be backed by actions to hold aloft the hopes they raise.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo is in the Middle East this week, and will deliver his own speech in Cairo, offering a preview of coming attractions on Middle East policy as the Trump administration enters its third year in office. Amid chaos at home—a shutdown, a manufactured border “crisis,” the administration’s ever-progressing legal troubles—there’s an opportunity for America’s top diplomat to speak candidly, clearly, and realistically to the region and its leaders.

Developing and implementing a durable, cohesive strategy is easier said than done in a volatile region where the worthiest goals in recent years have often been mugged by reality. Judging by the Trump administration’s first two years of Middle East policy and preliminary reports, we can expect a brittle mix of hawkish, confrontational rhetoric targeting Iran combined with unconditional support to flawed partners like Saudi Arabia. Pompeo may also try to put the best face on erratic moves by President Donald Trump in Syria—and to offer the latest version of a shifting policy that nobody can credibly pin down. He may even offer hints about the mythic peace plan that Jared Kushner has been working on for two years.

But at the end of the day, too often it has been pandering to regional leaders, rather than policy to shape their choices, that has guided the Trump administration’s behavior in the Middle East thus far. And if Pompeo wants to have a meaningful impact, whatever the strategy he is attempting to sell, there are three frank messages he should deliver instead to Middle East leaders in his Cairo speech.