Rashida Tlaib, a newly elected Democratic representative from Michigan, began her tenure in Congress by saying what most members of her party are merely thinking. “When your son looks at you and says, ‘Mamma, look, you won—bullies don’t win,’” she said at a MoveOn event in Washington shortly after her swearing-in ceremony. “And I said, ‘Baby, they don’t, because we’re gonna go in there and we’re gonna impeach the motherfucker!’”

The Oedipal jab at President Donald Trump prompted a wave of hand-wringing in Washington. Some observers expressed concern that the Democratic Party was following in Trump’s footsteps by abandoning civility in the public sphere. “Rep. Tlaib took the politics of Washington deeper down the drain,” Utah Senator Mitt Romney wrote on Twitter. “Elected leaders should elevate, not degrade, our public discourse.” Democrats fumed to reporters, for the most part anonymously, that the insult upset their party’s talking points on potential impeachment charges. “I don’t really like that kind of language,” Representative Jerrold Nadler, the Democratic chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, said on CNN.

While debates about civility in American politics are often performative, this one was revealing. Most of the criticism of Tlaib centered on her use of the word “motherfucker” rather than her substantive point, leaving Trump to be his own loudest defender against the idea of removing him from office. “How do you impeach a president who has won perhaps the greatest election of all time, done nothing wrong (no Collusion with Russia, it was the Dems that Colluded), had the most successful first two years of any president, and is the most popular Republican in party history 93%?” he wrote on Twitter last week.

Presidents typically don’t need to insist that they shouldn’t be impeached. That Trump feels compelled to do so signals that the impeachment process is effectively underway. The debate has moved beyond threshold questions, like whether impeachment is warranted, and the discussion now centers on practical and political considerations. The effort is unlikely to succeed, as things stand now. But even if nothing comes of these shadow impeachment proceedings, they still may serve a purpose: deterring Trump from further abuses of power.

Thanks to the results of last year’s midterm elections, there are almost certainly enough votes in the House to impeach Trump—and almost certainly not enough votes in the Republican-controlled Senate to convict him. Even if the entire Democratic caucus voted to convict Trump, twenty Republican senators would need to join them to oust him from office. That’s an extraordinarily high barrier for Trump’s opponents to overcome in a hyper-partisan climate. Support for impeachment may also wane overall as 2020 draws closer; lawmakers and the public may be uncomfortable with removing a president from office so close to an election, which could accomplish the same result but with greater political legitimacy.

In some ways, this is a familiar debate. Impeachment threats became a staple of American presidencies after the House impeached Bill Clinton in 1998. (He was subsequently acquitted by the Senate the following year.) Some Democrats in Congress, mostly on the party’s left wing, filed articles of impeachment against George W. Bush related to the Iraq War, administration scandals, and other topics. A smaller number of Republicans proposed impeaching Barack Obama during his presidency. None of these efforts attracted mainstream support, however, and party leaders ultimately squelched them in the House before they went far.

This time is different. Trump is openly hostile to any constraints on his power. He castigates federal judges who rule against him so frequently and so vehemently that Chief Justice John Roberts publicly came to their defense last year. While Congress refuses to fund his border wall, he has threatened to declare a national emergency to secure the funds without congressional approval. Trump is also averse to basic democratic principles. When polls showed him trailing ahead of the 2016 presidential election, he spread false allegations that the election was rigged against him. During last year’s midterms, he deployed the military within U.S. borders as a partisan campaign stunt.

Elections are typically the best means for removing presidents for bad policies or general incompetence. Impeachment is supposed to be reserved for serious abuses of power, or when the office-holder threatens the integrity of American democracy. There’s a strong case to be made for impeaching Trump on those grounds. The New York Times’ David Leonhardt laid out four specific reasons last week: for using the presidency to enrich himself and his businesses, for violating campaign-finance laws during the 2016 election, by obstructing justice during the Russia investigation, and by subverting the nation’s democratic structures throughout his presidency.

A serious challenge for any impeachment effort is the lack of precedent for it. There have been two presidential impeachment trials over the last 230 years, and neither ended in his removal from office. (Richard Nixon resigned before the House could impeach him after learning his conviction would be virtually certain in the Senate.) So while there are plenty of ways to show how impeachment can fail, there is none showing it can succeed. The Constitution itself offers little guidance: Presidents can be impeached for “high crimes and misdemeanors,” which can mean whatever the House and Senate want it to mean.

There are questions about timing, too. Should Democrats wait for special counsel Robert Mueller to wrap up his investigation into the 2016 election? His findings could significantly bolster the case for impeaching Trump if they’re made public. But the special counsel has given no indication about his progress or timetable. Similar investigations during previous administrations dragged on for years before wrapping up. By waiting for Mueller, Democrats could ultimately miss their best shot. But until Mueller concludes his independent inquiry, Republican senators may have an easier time dismissing impeachment as a partisan stunt.

And what about public opinion? Americans decisively moved last November to elect a House of Representatives that would serve as a check on the president. But only 43 percent of Americans told CNN pollsters last month that they support Trump’s impeachment and removal from office, while 50 percent opposed it. Then again, the public also isn’t as steadfastly opposed to the idea as it was in 1998. Bill Clinton’s approval ratings actually went up as the proceedings went on, and peaked as the House impeached him. I noted last year that the Republicans’ quest to remove Clinton serves as a warning of sorts for Democrats who hope to mount a similar effort against Trump. Unambiguous public support for impeachment may not be enough to oust Trump, but it’s hard to see a successful effort without it.

Barring some major developments, it’s hard to envision a scenario where Trump is removed from power by Congress. That doesn’t mean he’s free from accountability, of course. Lawmakers can still use their oversight powers to investigate the administration and uncover wrongdoing. I noted last month that the greater risk at the moment for Trump is that he’ll be indicted after leaving office, perhaps on campaign-finance charges related to the hush-money payments he made in 2016. He’ll also face the ultimate reckoning from voters in 2020.

None of this means that the ongoing impeachment debate isn’t worth having. According to a New York Times report in November, Trump tried to order the Justice Department to prosecute former presidential rival Hillary Clinton and former FBI Director James Comey last spring. Targeting political opponents for criminal prosecution on dubious grounds at best is a clear abuse of power and a hallmark of authoritarian rule. The Times reported that he backed down after Don McGahn, the White House counsel at the time, warned that it could lead to his impeachment. Sometimes a weapon is more effective when it isn’t used.

Joe Biden is yet again on the verge of announcing a presidential run. Despite twice falling far short of the Democratic nomination, in 1988 and 2008, the 76-year-old Biden is convinced not only that he can win it, but that he’s the best candidate to beat the president. On Sunday, The New York Times reported that the former vice president “has told allies he is skeptical the other Democrats eyeing the White House can defeat President Trump” and that he may make a formal announcement in a matter of weeks. “If you can persuade me there is somebody better who can win, I’m happy not to do it,” Biden reportedly told a Democratic supporter in private. “But I don’t see the candidate who can clearly do what has to be done to win.”

It’s easy to glean what he believes needs to be done to win: appeal to working-class whites, particularly in states like Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. “We can’t possibly in my view win the presidency unless we can begin to reclaim those white working-class voters that used to vote for us,” he said while campaigning in the lead-up to November’s midterm elections. Some in the party, including Biden himself, believe that the brash son of Scranton who famously rode the train to work is the kind of Democrat who can connect with disaffected voters, return the Midwest to the Democrats, and topple Trump.

But these Democrats are exaggerating Biden’s appeal, underestimating the strength of his potential primary opponents, and promoting a dangerously myopic view of the electoral landscape. By fixating on the Rust Belt states that narrowly cost Hillary Clinton the presidency, they’re neglecting the much broader swath of core Democratic voters who can deliver a victory against a historically weak president.

Trump’s appeal to working-class white voters has been obsessed over since his 2016 upset, but he merely benefitted a growing trend: The GOP has polled increasingly well with non-college-educated white voters for the past decade. “Whites who did not attend college were evenly split between the two parties in Pew surveys conducted from 1992 to 2008,” the authors of Identity Crisis, the definitive account of the 2016 election, wrote. “But by 2015, white voters who had a high school degree or less were 24 percentage points more Republican than Democratic (57%-33%).”

The Clinton campaign’s overconfidence that the “blue wall” would hold has been justly criticized, given that just 80,000 voters across Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin cost her the election. But there’s little evidence that the campaign’s midwestern ground game, and specifically its decision not to campaign in Wisconsin, made the difference. Instead a general lack of electoral enthusiasm, Clinton’s baggage (both overstated and deserved), and the Comey letter proved to be more decisive. Yes, Trump won a record share of the white-working class vote, but the same group of voters made up a quarter of Clinton’s coalition.

Despite the political class’ fixation on economic anxiety, the authors of Identity Crisis found that it was an isolated, partisan phenomenon: Republicans earning more than $100,000 a year were more concerned about the economy than Democrats earning less than $20,000. Instead, cultural anxiety was more decisive. “Economic anxiety had been decreasing, not increasing, in the eight years before 2016 and any impact it had was muted or at least not particularly distinctive compared to earlier elections,” John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck wrote. “When economic anxiety was refracted through social identities, however, the combination was potent. The important sentiment was not ‘I might lose my job’ but, in essence, ‘People in my group are losing jobs to that other group.’ Instead of a pure economic anxiety, what mattered was ‘racialized economics.’”

The argument for Biden is that his blue-collar bona fides and tough talk will win back these voters. “If you look at Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, the labor folks who voted for Trump, they love him,” former Delaware governor Jack Markell told the Times about Biden. “He has a connection with these people.” But it’s unclear how Biden’s political approach will appeal to voters motivated by cultural anxiety and “racialized economics.” It’s possible that the kind of economic platform that Biden is expected to pitch—one that stops short of Bernie Sanders’s democratic socialism, but nevertheless focuses directly on workers—could be effective here. But there’s nothing about Biden, outside of his identity as an old white man who reps Scranton, that suggests that he can be the only messenger who will be effective in making a dent in Trump’s non-college-educated white base.

For one thing, as Slate’s Ben Mathis-Lilley notes, “in 2018, Democrats flipped eight House districts that Obama won in 2012 but that Trump won in 2016; of those districts, which are in Biden’s ostensible wheelhouse, five were won by non-white male candidates.” Senators in the Biden mode, like Missouri’s Claire McCaskill and Indiana’s Joe Donnelly—both of whom Biden campaigned for—got walloped. Midterm voting suggests that the blue wall is being rebuilt by a diverse array of candidates, some similar to Biden (like Pennsylvania’s Conor Lamb) and some not (like Michigan’s Rashida Tlaib). There are strong signs that Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin are poised to return to the Democratic fold in 2020, though Ohio, where Republicans expanded their hold on state government, may be lost for good.

It’s true that Biden is very popular, leading the potential Democratic field by as many as 20 points. But there’s reason to believe that his support is inflated. His significant advantage in name recognition will shrink as the primaries take shape, and the scrutiny of his record will intensify. By sitting out the 2016 primary, Biden’s record largely remained unexamined, thereby preserving his image as an affable, everyman vice president. But there are plenty of blemishes, including his shameful role during the Anita Hill hearings and his role in passing the 1994 crime bill—the virtues of which he continues to extol. He also hasn’t proven to be an effective presidential candidate: His 1988 campaign was derailed by plagiarism accusations, and he dropped out of the 2008 race after getting just 4 percent in the Iowa caucuses.

The notion that Biden is the only Democrat who can beat Trump vastly overstates the president’s strength as a candidate. Trump has never even flirted with 50 percent approval during his two years in office, and the blue wave in the November midterms showed just how deeply he is loathed by a majority of the electorate. It’s likely that any Democratic nominee will be favored to defeat him. But it would be both strategically foolish, and politically disastrous, for the Democrats to nominate a candidate who sought primarily to appeal to tens of thousands of midwestern voters rather than the many millions who are already eager to help the party take down the president.

The third season of HBO’s True Detective is a return to the first season’s template. This is a response to the errant season two, a much-derided foray into urban policing, corruption, and masculinity. Season two was not, by any stretch of the imagination, a terrible piece of television. But the show’s debut season was simply so good that its sequel was doomed to struggle. In that first eight-part series we watched the classic cop two-hander transform into Bayou-sodden philosophy. The “straight man” was Woody Harrelson as Marty Hart, a philandering father who is undone by his lack of self-awareness. The “maverick” was Matthew McConaughey as Rust Cohle, a man with forearms hewn from oak, a tragic past, and a mind made out of razor blades.

The central conceit of season one was its double-layered narrative. Along one timeline, in 1995, Rust and Marty hunt a rather baroque serial killer. Along the other timeline, over in 2012, two younger cops question our heroes about how Timeline One went down. They suspect that Rust, who by now has taken to mustache-growing and expressing himself in gnomic expressions (“Time is a flat circle”) might himself be the killer. They never got the guy after all—was he under their noses all along?

The two timelines merge into a denouement complete with acid flashbacks, revelations about the meaning of life, and multiple stab-wounds. It was a highly conceptual show, mostly in its focus on philosophical pessimism, but Rust’s sexiness and his love of cocaine and pull-ups (at the same time) kept it entertaining. The final effect was of a gratifying meditation on time and relationships, where narrative form reflected the philosophy espoused by its characters.

True Detective has returned to its original shape in season three. In fact, the repetition is so heavy that it’s a little off-putting. Once again, two younger cops question a pair of aged detectives about a cold case. Once again, we’re in the South—Arkansas’s Ozarks, this time. Once again, we have a complex hottie (Mahershala Ali as Wayne Hays) doing the maverick genius thing, paired with a by-the-book redneck played by aging Hollywood royalty (Stephen Dorff as Roland West). Once again, the partners fall out dramatically, only to reunite in retirement. Once again, there are creepy dolls at the murder scene. And once again, multiple timelines play out through testimony, memory, and tape.

HBO / Warrick Page

HBO / Warrick PageThis time, however, there are three stories. Leaving its delicious production aside, True Detective should be credited with giving us the best aging makeup television has ever seen. This new season spans something like five decades, and never looks wrong.

Timeline A shows Wayne and Roland on the case of a missing pair of children in 1980. Timeline B sees the case re-opened ten years later; Wayne’s hair is shorter and by now he is married, to the lovely schoolteacher named Amelia whom he met in Timeline A. Timeline C is the cruelest: Now in retirement, Wayne is struggling to remember his life through the cloud of dementia. A television crew in the model of the podcast Serial has dug up new evidence on the case, and put him in front of a camera. Slowly and reluctantly, Wayne confronts memories of his marriage (Carmen Ejogo plays Amelia with enigmatic appeal) and of the unsolved case. Between hallucinating his wife and waking up in his bathrobe in the middle of the street, Wayne drags Roland out of retirement for one more crack at the mystery. “C’mon,” Wayne says to Roland through old-man tears. “Stir some shit up with me.”

So, yes—this is almost exactly the same TV show that you watched in 2014. But certain changes mark it out. This season features a love story, which adds a little schmaltz and heartache to the proceedings. It’s also much more serious about historical detail. Wayne Hays has the nickname “Purple Haze” from Vietnam, where he learned to track the enemy and suppress his emotions—skills he reprises while on the job. He’s also, obviously, black, working as a cop in the Deep South. While race was a small plot point in season one—the cops who interview the older detectives are both black and Marty calls them “young studs” at one point, to raised eyebrows—it is here at the forefront. N-words abound, and color is integral to the relationship between the two main cops.

The other great difference is Mahershala Ali himself. As the maverick, Matthew McConaughey was great. But Ali manages to outdo him, if only because season three demands so much more. He appears in the majority of scenes in the show, inhabiting three different stages in a single man’s life. The show is eight episodes long, so in terms of screen time it’s as if he has played three different roles in a trio of movies, back to back. The achievement is extraordinary, particularly because he does such a fine job of distinguishing the 30-something man from the 40-something man from the elderly man. The first is restrained but headstrong; the second hamstrung by emotional repression; the last abandoned, almost, to the flood of feeling that he has kept back for so long. His creased regret as an elderly man is impossible not to believe.

In the first five episodes, at least, there is not much new to True Detective round three in terms of the basic set-up. But in its narrative ambition and the great strength of its star, this show has managed to surpass its original outing. Love and time are the great motifs of True Detective and have been since its beginning. At the end of this triple-layered show, we ought to witness those themes configured in unprecedented dimensions. If nothing else, it should garner Ali better roles, more exposure, and bigger checks: No mystery there.

When Kristen Roupenian’s New Yorker short story “Cat Person” became a five-alarm sensation late last year, critics rushed to explain its popularity in terms of its relatability and quality. In its outlines, the plot seems standard enough: Twenty-year-old college student Margot begins a brief, frustratingly hot-and-cold relationship with the older Robert, vacillating between affection and revulsion as she tries to read his motives; when she finally gives up and breaks it off, his reaction exposes him as a boring misogynist. But “Cat Person” soon became the most-read piece of fiction ever on The New Yorker web site, prompting the blooming of a thousand takes and landing its author a million-dollar book deal.

YOU KNOW YOU WANT THIS by Kristen Roupenian Gallery/Scout Press, 240 pp., $24.99

YOU KNOW YOU WANT THIS by Kristen Roupenian Gallery/Scout Press, 240 pp., $24.99Fiction’s not supposed to go viral. The poet Rupi Kaur’s huge following makes sense to me; her brevity, simplicity, and hyper-earnest aesthetic play well on Instagram. But why did “Cat Person” cause such a ruckus? Did its page views reflect its objective superiority over all other contemporary fiction? Or was it, as some critics argued, mistaken for a fictional think piece about “our political moment,” shared more as an expression of political membership than of genuine appreciation? If it was, you’d expect comparable success for stories like Lynn Coady’s “Someone Is Recording” or Sana Krasikov’s “Ways and Means,” explicit responses to post-#MeToo gender politics, or Madeleine Schwartz’s “Collusion,” which is doubly timely in addressing both sexual misconduct and Russian politics.

It may be better to consider “Cat Person” a well-timed (though no-less-well-written) contribution to an existing genre, a high-water mark in the tide of righteous 2010s literature grappling with male entitlement and abuses of power. You can read its emergence as the postelection complement to a slightly earlier boom of novels about female friendship, the ones that usually had “Girl” or “Friend” somewhere in the title. Books about shitty men constitute one of a handful of literary movements responding to contemporary American society, along with Young Adult authoritarian dystopias, poems about drones, cli-fi, and stories about technology leaving us lonely or dead.

I wouldn’t be the first to argue that the herald of this current wave was Helen DeWitt’s 2011 satire Lightning Rods, a novel about a salesman who proposes a counterintuitive, depraved method to end workplace sexual harassment (which just so happens to align with his own sexual fantasies). Adelle Waldman’s The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.—about an emotionally dishonest young novelist and his failed relationships—in 2013 was another early entry, and Rebecca Solnit’s essay “Men Explain Things to Me” brought the concept of mansplaining to the mainstream. Now it’s 2019, and the biome is teeming: Alissa Nutting goes sci-fi in Made for Love, Kate Walbert’s His Favorites transposes sexual harassment to high school, and Claire Vaye Watkins’s “On Pandering” and Lili Loofbourow’s “The Male Glance” reassess the ways men read stories by women. More is on its way, judging by upcoming titles like Terrible Men and How to Date Men When You Hate Men. Even men have barged in, with Andrew Martin’s Early Work and Teddy Wayne’s Loner serving up variations on the fictional male mea culpa.

Point is, lots of great recent writing gets male shittiness dead to rights, so that’s not what sets “Cat Person” apart. Personally I like how it painstakingly draws out the exhausting mental flowcharts and loop-de-loops it takes to try to understand someone—Margot puzzling over Robert’s dolphin emojis, whether she can feel safe in his car, what’s up with his cats—and how exasperating it is when the effort isn’t reciprocated. Margot’s idea of Robert swings between romantic projection and cynicism and false epiphany until the brutal snap-resolution of the final word, Robert’s ugly slur. You could argue that delivering such a neat verdict on Robert forgoes nuance, that letting us dwell in eternal uncertainty would’ve been richer or truer to human nature; I contend that a person can both contain multitudes and still be a thoroughgoing asshole.

In the twelve stories in Roupenian’s debut, You Know You Want This: “Cat Person” and Other Stories, she establishes herself as a raucous and bloodthirsty storyteller who, even when she stumbles, never bores. There are only a few more stories of disastrous dates here; it’s just one part of a larger project about human sadism. More than anything else, You Know You Want This is a sanguinarium of gothic horror, less Carrie Bradshaw than Carrie White doused in pig blood. (Roupenian is an alumna of Clarion, the vaunted sci-fi/fantasy workshop, and a self-professed Stephen King superfan.) Its profusion of body horror reminds me of Amelia Gray’s Gutshot or Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties, books whose psychological violence has a gruesome physical edge. Nearly every story in You Know You Want This has someone getting stabbed, strangled, slashed, gouged, degloved, immolated, bludgeoned, bled out, brain-injured, or asswhupped.

I suspect Roupenian knew “Cat Person” would jaundice readers’ expectations one way or another, and she exploited this by opening the collection with “Bad Boy,” a title that might suggest another misogynist miscreant. The couple who narrate the story torment their friend, a sad-sack guy fresh off a breakup who’s crashing on their couch. They tease him by having noisy sex in the next room; when they realize that degrading him turns them on, they coerce him into a ménage à trois full of “pain and bruises, chains and toys,” escalating to a frenzy of deadly transgression that feels like an homage to Georges Bataille’s ultra-obscene novel Story of the Eye: “No matter what we did, he wouldn’t stop us. No matter what we told him to do, he would never, ever say no.”

It only takes a few stories, or maybe even just the title, to see that they all play off the same Nietzschean character archetypes: the weak dominated by the strong, victim versus victor. The victims are sensitive, passive introverts, forever in their own heads, wavering between reluctance and compliance. The victors, meanwhile, look just like you and me: Their innocent, kind, or seductive facades conceal a poisonous nature, like the appetizing rainbow slick of petroleum coating a dead ocean. The victim compounds their own suffering by over-empathizing with their tormentor, who is only emboldened by shows of vulnerability. After an eleventh-hour plot twist, the dynamic abruptly shifts, and someone either dies or is scarred.

That’s not to say the stories are cookie-cutter, but that they each take a different angle on this particular model of human affairs. Actually, one of the book’s strengths is how diverse its styles and genres are, as it twists the formula of weak versus strong. Sometimes Roupenian will hint at an ending, only to dislocate it. In “Look at Your Game, Girl,” a preteen girl is approached by a threatening drifter; the violence we anticipate does occur, but not to the person we think it would. Then there are genre departures: Roupenian’s fairy tale “The Mirror, the Bucket, and the Old Thigh Bone” presents a finicky but kindhearted princess who, dissatisfied with every suitor in the land, ends up accidentally infatuated with her mirror reflection. “What can this mean but that I am spoiled, and selfish, and arrogant, and that I am capable of loving nothing but a distorted reflection of my own twisted heart?” she laments, realizing what’s happened. She’s able to suppress her autosexuality for a few years, but when her caring King gives her a chance to indulge herself, her self-regard takes over. Unlike Narcissus, she doesn’t melt away into a flower. She turns into something hideous and dangerous. In Roupenian’s moral universe, the customary literary virtues of empathy, a strong conscience, and anxious self-doubt achieve nothing and save no one.

The antagonists in these stories are not always who you’d expect. As if intended to frustrate critics eager to slap a #MeToo sticker on the book, several stories flip the usual scripts of power. The female narrator of “Scarred” imprisons and tortures a man in order to harvest from him the blood and tears that her dark magic spells require. In “Death Wish,” a petite woman insists on being life-threateningly beaten by her reluctant Tinder date. (We already know what he’s going to do—Roupenian seldom pulls a punch.) “The Night Runner” has a feckless Peace Corps teacher terrorized by his class of Kenyan schoolgirls because he refuses to beat them; they hurl garbage at him and mock his feline eyes, making him the sorrier of the collection’s two cat people. And in “Sardines,” a jilted woman fantasizes about “swapping the lube in [her ex’s] girlfriend’s bedroom drawer with superglue, tying her down and tattooing slut across her face.” True to form, what ends up happening to the girlfriend is considerably worse.

But not all the stories are so easily reduced to pure will-to-power scenarios, and one of its standouts, “The Boy in the Pool,” is an unexpectedly sweet story about a woman planning a bachelorette party for her former high school crush. She manipulates a has-been actor into becoming a glorified escort and live-reenacting the bride-to-be’s favorite sex scene from the TV horror movie he once starred in. Though the outcome is heartwarming rather than chest-ripping, the book’s themes still lurk in the wings: The actor’s appeal is that he’s “a boy who will kiss your feet and be grateful for it, a boy who suffers, a boy who will suffer for you”; in the film, a straight-to-video schlockfest called Blood Sins, he has a phrase carved into his body: “Love breeds monsters.” With this the book reaffirms its commitment to christening even the tenderest story with at least a drop of blood.

Clearly none of this will appeal to the squeamish, to anyone who’s not in the market for “a puddle of sentient, erupting flesh” or a “gushing surge of dark red blood.” You’ll probably also want to pass if moral gray zones are your thing, since, as in “Cat Person,” the endings tend to eschew nuance in favor of clarity and intensity. Sometimes this makes the gore less gothic than goofy. The prose is intelligent, though generally plain and conversational, with the occasional whoopsie-doodle of a cliché (“It started to get under our skin,” “lithe as a cat,” “burst into tears,” “dissolved into tears”). You could call Roupenian’s approach to description spare if you’re feeling generous, vague if not.

The big exception is when she aims for the stomach, as when she describes a writhing blood-slick parasite as “a six-inch-long tube of knobbed white flesh, lined with a thousand shivering legs that wave like seaweed.” She slathers even the most innocuous pastoral imagery with erotic Baudelairean macabre, as in this description of a forest:

The vaginal lips of a pink lady’s slipper peep out from behind some bushes; a rubber shred of burst balloon, studded by a plump red navel knot, dangles from a tree branch, and the corpse of a crushed mushroom gleams sad and cold and pale.

You can see how the book deals with feelings viscerally, an approach neatly symbolized by the recurring images of corrupted hearts. Here the human heart is not the poetic locus of love, but the pulsing, fallible organ pumping atop our livers, or beneath our floorboards. It first appears in the epigraph: “There is something jerking in your ribcage / that is not a heart / It is cow-intestine white / & fibrous & gilled.” The anti-hearts of this book are not healed or changed; they’re carved from chests and infested with parasites. The heart is a lonely hunter, deceitful above all else, it wants what it wants, and when it shows up, it’s never good news—you’ll know exactly what Roupenian means when the softboy protagonist of “The Good Guy” calls a woman his “sweetheart.”

The heart is a lonely hunter, deceitful above all else, it wants what it wants, and when it shows up, it’s never good news.And about that—if you do want more “Cat Person,” then “The Good Guy,” the collection’s best and longest story, is the perfect follow-up: a 50-pager that plumbs the benthic depths of just how manipulative and self-serving a guy can be, while genuinely seeing himself as a loyal, blameless ally. “Good-old friendly, utterly dishonest Ted” is someone who considers himself a nice guy while acknowledging the perils of being a “Nice Guy”; who says things to women like “I’m so sorry. That sounds really hard,” but only achieves erection by “pretend[ing] that his dick was a knife, and the woman he was fucking was stabbing herself with it.” The story does the emotional autopsy of “Cat Person” from the vantage of the cryptocreep, and it’ll have you covering your eyes and reading through your fingers. “Biter,” the final story, also offers a bit of #MeToo catharsis and thematic closure, as a victim of sexual harassment discovers a way to get revenge and provide cover for her own dark appetite.

Although You Know You Want This may be timely in its occasional adjacency to #MeToo, its real canniness comes from apprehending the psychology not only of power, but of power-hunger as, itself, a form of weakness: how people harbor an impulse toward sadistic narcissism, and how little it takes for them to succumb to it. Taken together, the uncommonly clear moral of these dark fables is that, given enough of an opportunity, even the kindest, most thoughtful people can be driven to gleefully, passionately hurt and exploit others just to satisfy their desires. Those without consciences will conscript you into their grotesque fantasies, turn you into whomever they want you to be, wreaking any amount of targeted violence and collateral damage; if you survive, you’ll be left to catalog your scars. Power only inflames this tendency and helps people get away with it.

Speaking of power, seeing how readers approach Roupenian’s collection will surely say something about us: No matter the book’s merit, maybe we’ll act on the perverse desire to see the much-hyped book tank, flop, or disappoint the standards of literature or feminism, just to feed our sadistic inner critic its blood meal of schadenfreude. That would only redound to Roupenian’s success, because she knows we want this.

Scarcely a week into Jair Bolsonaro’s tenure as president of Brazil, protections for the environment and indigenous and LGBTQ populations have been removed, and both the neoliberal economic policies closely associated in Latin America with the thirteen-year Chilean dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, and the language of Brazil’s military junta, which ruled from 1964 to 1985, have resurfaced. “I come before the nation today, a day in which the people have rid themselves of socialism, the inversion of values, statism, and political correctness,” Bolsonaro told his inaugural crowd, pleasing Brazil’s elites and the stock market. His call for surgical violence—Brazil’s “whole body needs amputating” was the memorable phrase—left others fearful of a return to “disappeared” bodies and torture cells.

Threat is a fundamental tool of the 21st-century authoritarians on the rise: Dominating is much easier if you’ve prepared people to be afraid of you when you take office. Bolsonaro used it to sell himself as the only candidate capable of tackling Brazil’s soaring violence problem, which included a record murder rate in 2017. “A good criminal is a dead criminal,” he said last fall, earning comparisons to Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, who has made good on his own campaign promises to carry out extrajudicial killings of those involved in his country’s drug trade.

Yet Bolsonaro has also preventively criminalized all leftists and other political opponents, promising to send such “red outlaws” to prison or into exile. “It will be a cleanup the likes of which has never been seen in Brazilian history,” he said in October, raising the possibility that he might aspire to be even harsher than the former junta, which he believes didn’t kill enough people. Years of documented Bolsonaro hate speech against gays and blacks suggest other potential targets, although even if he gets a ruling majority in parliament, “cleansing” an enormous country with a multiracial and ethnically complex population would be a Herculean task.

The slew of executive order legislation following Bolsonaro’s inauguration has hewed closely to the authoritarian playbook, designed to further intimidate the population, cement Bolsonaro’s profile as a “get things done” disrupter from outside the political establishment, and, most importantly, reassure the conservative elites who have always backed such leaders that they will profit handsomely with him in office. The summary removal of indigenous peoples from protection by the Human Rights Ministry (which may go the way of the newly suppressed Labor Ministry) supplements the planned merger of the Environmental and Agricultural Ministries, which will put indigenous lands up for grabs by logging and other agribusiness interests, helped by the highway Bolsonaro envisions building through the Amazon rainforest.

During the Pinochet regime, University of Chicago and Harvard-educated neoliberal economists propping up the dictatorship through spending cuts and privatization were known as “Chicago Boys.” The day following the inauguration, Bolsonaro had his very own Chicago Boy sworn in as Economy Minister: Paulo Guedes, a Milton Friedman-influenced neoliberal who taught economics in Chile during the Pinochet era. Joaquim Levy, the new head of the Brazilian Development Bank, and Roberto Castello Branco, the new chief executive of the oil and natural gas company Petrobras, are also Chicago economics alumni. The Brazilian economy, long stagnant, definitely needs reforms. But, as of yet, Bolsonarans seem untroubled by the fact that neoliberal successes in Chile capitalized on the “advantages” of authoritarian oppression—bans on unions and strikes and the absence of a political opposition.

The precedent of military rule in Brazil makes him more dangerous than his United States counterpart.Bolsonaro’s savvy appointment of popular corruption fighter Sergio Moro to lead an expanded Ministry of Justice continues an election persona that for many voters seemed to promise “a deep change in the political establishment,” as Rodrigo Craveiro, a journalist with Brazilian daily Correio Braziliense, wrote to me by email. Yet Bolsonaro would be the unusual authoritarian if he eradicated corruption; he’ll more likely use the moral high ground of anti-corruption to neutralize his political enemies and purge the bureaucracy, the better to populate it with loyalists. Certainly, Bolsonaro has benefited from the corruption scandals that have rocked the traditional political class—widely popular President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who might have defeated Bolsonaro had he not been barred from seeking election in 2018, is now serving a twelve-year jail sentence, while his successor, Dilma Rousseff, was impeached in 2016. Moro, the ex-judge who jailed da Silva, and who is crucial for this first phase, may find himself cast aside later.

Bolsonaro, a career politician, used his military background as a paratrooper to separate himself from the corrupt reputations of other career politicians, playing on the idea that the military is nonpartisan, since serving officers are forbidden from making political statements. One-third of his cabinet positions have gone to military officers; a retired general, Hamilton Mourão, is his vice president. It seems the post-dictatorship wariness of having the military play an active role in politics has waned—an increasing number of Brazilians want “law and order” government regardless of the consequences.

“Bolsonaro is as much an apparition from Brazil’s past as a harbinger of its future,” historian Kenneth Serbin wrote at Foreign Affairs the day of the inauguration: Only a “politics of forgetting” about the violence of the military dictatorship has made his ascent possible. I’d go further: Bolsonaro advances a new phase of remembrance that rehabilitates the people and causes of that terrible time. During the 2016 congressional proceedings leading to Rousseff’s impeachment, Bolsonaro dedicated his vote against her to her torturer—Colonel Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra, de facto chief of army intelligence services, which ordered Rousseff, then a leftist guerrilla, tortured for three weeks in 1970 (she was then a political prisoner for two years). Sympathizers like Bolsonaro publicly honor those who subjected Brazilians to torture methods such as “the barbecue,” where victims were tied to a metal rack and given electric shocks on and inside their bodies.

Bolsonaro may be called the “Trump of the Tropics” for his impolitic and often incoherent remarks, his skill with social media, and hodge-podge coalition of Evangelical Christians, military toughs, and business elites. But the precedent of military rule in Brazil makes him more dangerous than his United States counterpart. In 1999, Bolsonaro declared that if he ever became president he’d immediately launch a coup and declare himself dictator. Twenty years later, he’s in power. Time will tell what kind of strongman he will be.

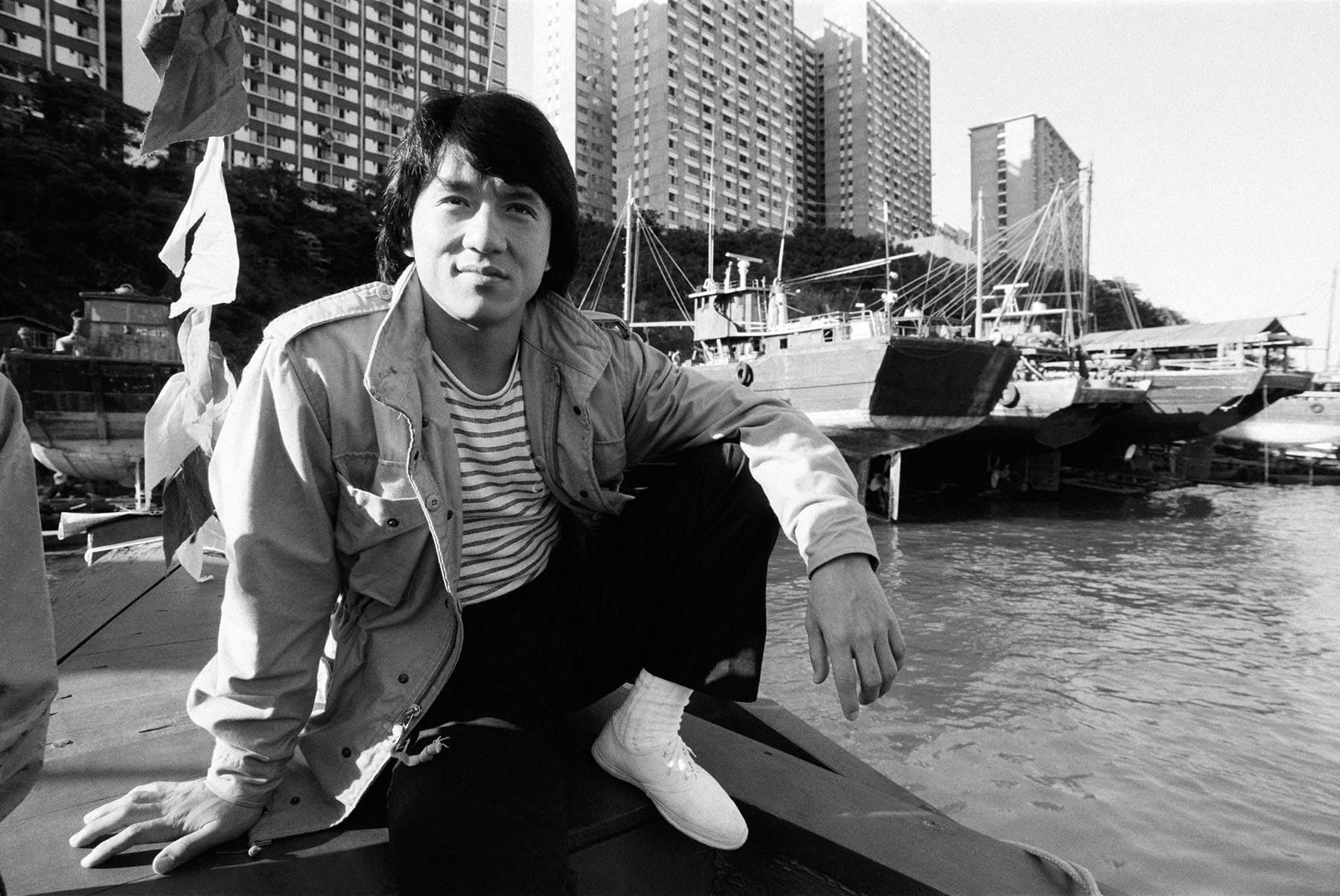

There are many ways to tell the story of Jackie Chan. He is the heir to Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, the comic grace of his movements leaving audiences in laughing wonder. He’s also the heir to Bruce Lee: If Lee broke old stereotypes about the Asian man being frail and craven, then Chan reinvented him once more, offering across dozens of movies a consistent character who was almost childlike in his cheerfulness, known as much for his winking smile as for the fury of his fists. Before 1995’s Rumble in the Bronx made him a household name in America, he was a filmmaker’s filmmaker, his elaborate fight sequences and death-enticing stunts the objects of devoted study by Steven Spielberg and James Cameron. And he helped bring martial arts into the Hollywood mainstream, so that nearly every American action hero, from Jason Bourne to the Black Panther, now boasts elements of karate or jujitsu in their repertoire of ass-kicking skills. The transfer was symbolically completed in 1999’s The Matrix, when Keanu Reeves, having downloaded a fighting program to his brain, opens his eyes and reverently whispers, “I know kung fu.”

These aspects of the Chan legend are all present in his new memoir, Never Grow Up, as the threads of an unlikely rags-to-riches story. The child of a cook and a maid—a “servant’s kid,” as he was derisively called—he rose from virtually nothing to become the most famous Chinese entertainer on earth. In the book’s introduction, his world-straddling triumph is represented by the lifetime achievement Oscar that he received in 2016, the only time it has ever been bestowed on a Chinese filmmaker. (The book’s jacket features him holding the golden statue with his eyes closed, as if he is saying a prayer to it.) And like all rags-to-riches stories—whether it’s Daddy Warbucks rescuing little orphan Annie, or an Indian slumdog becoming a millionaire—Chan’s is ultimately a tale about the place where he was born and raised and first made his mark: Hong Kong, which over the course of his lifetime went from being the last significant outpost of the British Empire to an ambiguous outlier of an ascendant China.

Never Grow Up, in mostly inadvertent ways, thus offers another way of telling Jackie Chan’s story. It’s about colonialism, capitalism, and the myths we construct to justify living under both.

When Chan was born in 1954, Hong Kong was fast becoming a haven for Chinese escaping communist rule on the mainland. This tiny city-state, some 400 square miles in total, had historically served as a foothold for European merchants seeking to gain access to the Chinese market, as the historian Jan Morris recounts in her book Hong Kong. After Mao and his gang took over in 1949, however, Western trade with China was shut off and Hong Kong became its own focal point, a center for both finance and industry, ultimately transforming into a mighty symbol of capitalism’s wealth-creating power on the very doorstep of the world’s most populous communist nation. As China suffered through famine and political upheaval and one miserable five-year-plan after another, Hong Kong sprouted an endless number of skyscrapers, which seemed to cast long, mocking shadows over its massive neighbor.

NEVER GROW UP by Jackie Chan (with Zhu Mo)Gallery Books, 352 pp., $26.00

NEVER GROW UP by Jackie Chan (with Zhu Mo)Gallery Books, 352 pp., $26.00Chan’s parents, fleeing political persecution and seeking work, were among the emigrant laborers who formed the backbone of the Hong Kong economy in the immediate postwar decades. The Chans landed in Victoria Peak, a posh neighborhood high in the hills that is home to the wealthy and foreign diplomats. (It is now best known as a tourist site where one can take in Hong Kong’s famous topography from above, a bristling bowl of concrete and glass poised on the edge of the harbor.) Hong Kong was so important to the Chans that it was embedded in the name they gave their only son: Chan Kong-Sang, which means “born in Hong Kong.”

The British operated with a light touch in Hong Kong, at least compared to a place like New Delhi, which both administratively and culturally bore the deep imprint of empire. But Chan was nevertheless familiar with the racial dynamics of colonialism. His parents worked at the French consulate, “except we didn’t have a magnificent house that faced the street,” he writes. “Our home was run-down, small, and stuck in the back. The folks at the consulate treated us well, but from the very beginning, we existed in two different worlds.” He became enamored with a girl named Sophie, the “very beautiful” daughter of the French consul, and would stand up to boys who teased her, at one point thrashing the child of a French official. Chan’s father, terrified that he might lose his job, beat the young Chan with a belt, locked him in a shed for hours, then forced him to apologize to the boy and his family.

Jackie Chan in “The Legend of Drunken Master,” 1994 Photofest

Jackie Chan in “The Legend of Drunken Master,” 1994 PhotofestWhat impact these experiences had on Chan is hard to discern, since every episode in this memoir, even the most traumatic, is told with Chan’s indefatigable merriness, which as the book goes on starts to feel like a protective mechanism, a carapace of cheer. There is, too, an overarching sense of the phenomenal success that is to come, which casts a backwards glow even on those moments when Chan was at his lowest, cowering by the garbage bags in that lonely shed. Each trial is a stepping stone to the super-stardom that will legitimize everything that came before, rather than an examination of the ways in which being poor and Chinese in a colonial city in the 1950s might have messed a person up.

This blind spot is particularly apparent when Chan writes of the crucial formative experience in his life: When he was seven years old, his parents pulled him out of school and enrolled him at the China Drama Academy, which churned out performers for Peking operas and other entertainments. The Chans, who soon after would leave Hong Kong to pursue work in Australia, signed a ten-year contract with the academy, essentially consigning their son to a life of indentured servitude.

For ten years, Chan trained all day long, from 5 a.m. to 11 p.m., with breaks for lunch and dinner. Along with the other boys, he slept on a thin mat, on a carpet encrusted with sweat, spit, and piss. When he misbehaved, he was beaten with canes; when he fell ill, he was told to suck it up and keep practicing his kung fu. He received almost no education, not even in the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic, and when he first became rich he had trouble signing his own name on credit card receipts. (His memoir is “co-written” with a publicist.) He was, in effect, a walking slab of meat to be trotted out whenever a Peking opera production needed a singer or dancer or acrobat. And when he began seeking work on movie sets in his teens, his master would take a 90 percent cut of his pay.

Chan was enmeshed in the vast underclass of the great Hong Kong economy, which to this day is jam-packed with underpaid laborers from around the world who live stacked on top of each other in dismal apartments the size of coffins. And yet the predominant sense in this memoir is that the obvious inequities of the China Drama Academy particularly and Hong Kong more broadly were outweighed by the amazing opportunities they afforded to a nobody like Chan Kong-Sang. He describes those ten years as his “decade of darkness,” but, he adds, “It was in those ten years that I became Jackie Chan.”

In other words, what to my mind reads like a brutal account of exploitation and abuse is meant to be inspirational, a testament not only to Chan’s personal fortitude, but also to a certain ethic. Indeed, in Chan’s case, the myth of the self-made man, predicated on hard work and sacrifice, is taken to its extreme, for the thing he willingly sacrifices over and over again, year in and year out, is his body. The China Drama Academy primarily contributed to Chan’s success in three ways: It facilitated lifelong friendships with fellow entertainers, like Sammo Hung, who in the early days got him jobs, then went on to co-star in some of his most famous movies; it prepared him for stuntwork and trained him in martial arts, which were his calling cards in Hong Kong’s down-and-dirty film industry; and it turned his body into an instrument that could withstand ungodly amounts of pain.

One of his first breaks came when a director demanded a perilous stunt—a tumbling leap from a high balcony—without a wire to catch the stuntman if it went awry. The stunt coordinator refused to let any of his men perform it. Then Chan volunteered, breaking what amounted to an ad hoc labor strike. “What’s the matter with you?” the coordinator asked. “Are you tired of living?” Chan, of course, pulled off the stunt—twice—establishing his reputation as a daredevil. As he started to star in his own films, culminating in his 1978 breakthrough Drunken Master, original stuntwork became one of his defining traits, alongside his comedic mien. “I always perform my own stunts,” he promises to readers, “no matter how dangerous.” And with that came scores of injuries, which were then showed to audiences after the movie was over, in a highlight reel as the credits rolled. These injuries included a disastrous fall during the filming of Armour of God (1986) that nearly killed him.

In his memoir, Chan proudly recounts the body parts he has shattered over the course of his career: nose, jaw, ankle, cranium. “My leg sometimes gets dislocated when I’m showering,” he writes of the toll his work has taken on him. “I need my assistant to help me click it back in.” This is presented as evidence of his dedication to the craft. It is also what makes him exceptional—not his brilliance or his smile or any other quality, but an almost masochistic willingness to risk his life for the camera. Those highlight reels, full of impossible leaps from the tops of buildings and other brushes with death, became the hallmark of his movies, more memorable than their plots or characters. By the time Rumble in the Bronx came around in the 1990s, Chan’s antics represented the awesome possibilities of what a human being could do on screen, soon to be surpassed by the hypnotic fireworks of CGI. But read as a Hong Kong success story, it leaves the unfortunate impression that the only way to make it in this town was to literally almost kill yourself with work.

It is a shame that Chan is unable to evoke in his writing the joyful magic of a Jackie Chan fight scene. The combatants often work in an improbably tight space, with a few props that either shift position or are smashed to pieces, so that the space changes in surprising ways, as if some unexpected dimension of reality is continually unfolding before your eyes.

It is a shame, too, that Chan does not say much about his filmmaking style. His Hong Kong, for example, is not that of John Woo (who pioneered the gritty, hardboiled aesthetic of action movies much imitated by Quentin Tarantino) or Wong Kar Wai (all sharp angles and reflections and harsh light, where even the raindrops are lambent with neon). It is something plainer, more straightforward, a bit ugly even: milky-gray sky, drab office interiors, identical white apartment blocks rising from the green hills with the regularity of a picket fence. The principal charm of this aesthetic, like a yellowing photograph, comes from age, dating Hong Kong to a specific moment in the 1980s and early 1990s, when it was at its peak and looking toward the 1997 handover to China with equal measures of hope and trepidation.

The reader is left not with a reminder of Jackie Chan’s genius, but with the rather sad story of his very successful life. It is an old colonial tale, the hapless provincial who becomes worldly, though in Chan’s case he doesn’t evolve beyond being a clownish parvenu. He writes about it with his usual high spirits: “How did it feel to go from being flat broke to being a millionaire, practically overnight? To go from being an uneducated loser to being a famous star? It was fantastic!” He drinks all the time. He totals expensive cars and buys new ones. He spends millions of dollars on fancy watches, chases beautiful women, and licenses a Jackie Chan brand of Australian wines. After he stars in Rush Hour with Chris Tucker in 1998, he becomes a bona fide star in America, producing a series of comic-action movies in his middle to old age that make him richer and more famous still.

Jackie Chan as Chief Inspector Lee and Chris Tucker as Detective James Carter in 1998’s “Rush Hour.”Photofest

Jackie Chan as Chief Inspector Lee and Chris Tucker as Detective James Carter in 1998’s “Rush Hour.”PhotofestHe marries and has a child—named Jaycee, after his own initials J.C.—but he hardly ever sees his family because he is constantly working. (He also has a child out of wedlock though this only warrants an offhand sentence.) He is at his most self-aware when discussing his workaholism. “When I was young, people looked down on me,” he writes. “As a young adult, I lived in poverty. When I finally found success, I was driven to give the world one good film after another, to show everyone what I was worth.” He is rich beyond his wildest dreams, but is unable to shed the poor young man he once was, a person desperate for work and afraid of the abyss that could open up at his feet at any moment. His poverty is a wound that never quite heals.

Those searing experiences have not translated into a sympathetic politics. As Hong Kong was absorbed by China, and as the mainland’s own cities came to rival Hong Kong for wealth and power, it held on to the one trait that truly made it a British colony, which is that it was not a democracy. It would appear that Chan would like to keep it that way, viewing Hong Kong’s democratic movement as a blemish on its reputation for frictionless commerce and order. “Hong Kong has become a city of protest,” he complained in 2012. “People scold China’s leaders, or anything else they like, and protest against everything.” In 2009 he said, “I don’t know whether it is better to have freedom or to have no freedom. With too much freedom, it can get very chaotic. It could end up like in Taiwan.” He added, “Chinese people need to be controlled, otherwise they will do whatever they want.” Indeed, China’s authoritarian-capitalist model, with its billion-plus consumers looking to spend time at the movies, suits Chan very well. He has moved his base of operations to Beijing and become a kind of soft-power ambassador for the Communist Party. He has made nationalist-inflected movies with a mainland production company.

In 1996 Jackie Chan climbed the Hollywood sign . Julian Wasser/Hulton Archive/Getty

In 1996 Jackie Chan climbed the Hollywood sign . Julian Wasser/Hulton Archive/GettyIf Chan once represented what a Hong Konger could do with a little pluck and a little luck, his relentlessly buoyant memoir offers a different message: Life is hard, so one must be harder. It is an ethos that perhaps has been there all along. Police Story (1985), one of his best movies, concludes with an epic fight scene in a mega department store, that ubiquitous symbol of Hong Kong’s consumer economy. Against a backdrop of designer clothes and jewelry and electronics, Chan fights a whole gang of bad guys, sending them flying into mannequins and tumbling down escalators. There is shattered glass everywhere as bodies slam through display cases and storefronts. At one point, inexplicably, a motorcycle makes an appearance, careening through more panes of glass. When it looks like the head of the gang is about to get away, Chan leaps from the store’s top story onto a giant pole festooned with lights, sliding all the way down in a shower of electric sparks. (In his memoir he reveals he shouted the words “I die!” as he jumped.) He crashes into more glass at the bottom, and in one unbroken motion gets up and keeps fighting.

It remains a breathtaking scene, combining everything audiences have come to love about Jackie Chan: athleticism, derring-do, an everyman’s goodness. But there is something disturbing about it, too, the way Chan is both destroying and being destroyed by this mall. There is blood on his face, after all. And the blood is real.

Razer is getting into the PC case game with a pair of Tomahawk chassis, one of which has hydraulic glass doors that lift up like a sports car.

Razer is getting into the PC case game with a pair of Tomahawk chassis, one of which has hydraulic glass doors that lift up like a sports car. The Asus ROG Ranger BP3703 is the first bag we've ever seen that has rainbow LEDs on the outside and a host of cool features on the inside.

The Asus ROG Ranger BP3703 is the first bag we've ever seen that has rainbow LEDs on the outside and a host of cool features on the inside. We’re here live for Intel's CES 2019 keynote in Las Vegas where the company is expected to launch new processors and perhaps update us on its 10nm chips.

We’re here live for Intel's CES 2019 keynote in Las Vegas where the company is expected to launch new processors and perhaps update us on its 10nm chips. At CES in Las Vegas, Lenovo is updating its Legion line of gaming laptops along with bunch of new gaming accessories.

At CES in Las Vegas, Lenovo is updating its Legion line of gaming laptops along with bunch of new gaming accessories. MSI is adding Nvidia's RTX graphics to every laptop in its lineup, including the brand new GS75 Stealth.

MSI is adding Nvidia's RTX graphics to every laptop in its lineup, including the brand new GS75 Stealth. Intel's ongoing CPU shortage has reportedly given AMD the chance to get its processors into more laptops.

Intel's ongoing CPU shortage has reportedly given AMD the chance to get its processors into more laptops. CES 2019 has officially begun, and we have the latest news from the Las Vegas Convention Center show floor.

CES 2019 has officially begun, and we have the latest news from the Las Vegas Convention Center show floor. Whether you're looking for a sub-$1,000 system that runs mid-range games or a VR-ready battle station, we've found your deal.

Whether you're looking for a sub-$1,000 system that runs mid-range games or a VR-ready battle station, we've found your deal. The Alienware Area-51m spawns a new generation for the brand with desktop power in a laptop form.

The Alienware Area-51m spawns a new generation for the brand with desktop power in a laptop form. Dell announced the 2019 inductees in its G series gaming laptop lineup today. The G5 15, G7 15 and G7 17 arrive January 21 starting at $999 with up to Nvidia GeForce RTX 2080 graphics and a wide range of configuration options.

Dell announced the 2019 inductees in its G series gaming laptop lineup today. The G5 15, G7 15 and G7 17 arrive January 21 starting at $999 with up to Nvidia GeForce RTX 2080 graphics and a wide range of configuration options.

MSI unveiled its PS63 Modern laptop at CES 2019.

MSI unveiled its PS63 Modern laptop at CES 2019.

No comments :

Post a Comment