Donald Trump is perhaps the most unpopular president in recorded history, and he will soon face the most daunting re-election campaign in recent memory. Dogged by investigations and hamstrung by a lack of achievements, he has thus far failed to settle on a sharp message for 2020. “Promises Kept,” though less authoritarian, doesn’t have quite the ring of “Build the Wall” or “Lock Her Up.” But at Tuesday’s State of the Union, Trump unveiled what some advisers believe will be the winning message in November of next year. “Tonight,” he said, “we renew our resolve that America will never be a socialist country.” The Republicans in the chamber—nearly all rich white men—stood and applauded, while many Democrats scowled.

President Trump takes a direct shot at socialism: "Tonight, we renew our resolve that America will never be a socialist country." Sen. Bernie Sanders is seen frowning #SOTU https://t.co/EXZ8FU2DXV pic.twitter.com/WNNYm83eGD

— CBS News (@CBSNews) February 6, 2019Trump’s allies see this as a crucial argument heading in to 2020. After the State of the Union, Trump’s 2016 communications director, Jason Miller, told Axios’ Mike Allen that the president “elevated the wedge issue of ‘socialism’ in a way nobody else could.” Allen wrote that Republicans “loved ... the endorsement-by-sitting-in-silence when he hammered socialism.” With the border wall in limbo, little progress on a nuclear treaty with North Korea, and the 2017 tax cuts looking worse by the day, Trump doesn’t have any major accomplishments to campaign on beyond his Supreme Court appointments. But he does still have a strong economy. Trump is “trying to frame 2020 as another big, directional election ... betting that [his] people are going to actually like the direction the country is going,” another Trump campaign veteran told Allen.

Trump’s State of the Union paean to capitalism undoubtedly pleased his base, who have been the focal point of his entire presidency. But there are reasons to believe that making 2020 about “America First v. Socialism,” in Axios’ phrasing, might backfire for Trump. While the economy has continued to grow under Trump, there is rising dissatisfaction with income inequality and capitalism itself. Trump may think that red-baiting can make his toxic presidency appear to be the lesser of two evils. But this strategy requires taking greater ownership of a system that an increasing number of Americans think is unfair—and that didn’t work out so well for his Democratic opponent in the 2016 election.

Socialism’s long comeback in America began after the 2008 financial collapse, which made Americans keenly aware of the banking industry’s power and the country’s massive wealth inequality. “The richest Americans,” wrote Brown University economist Mark Blyth in his 2013 book Austerity, “own more assets than the bottom 150 million, while 46 million Americans, some 15 percent of the population, live in a family of four earning less than $22,314 per annum.” Outrage over inequality drove the creation of the Occupy Wall Street movement in New York City in 2011, and in 2016 it was the foundation of democratic socialist Bernie Sanders’s bid for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Sanders’s campaign ultimately failed, but it could be argued that he won in the long term. Today, nearly every major Democratic candidate for president endorses some version of universal health care, which would have been unthinkable even ten years ago. The Democratic primary will be fought over issues like how to reduce inequality and tax the rich, as well as on costly spending programs like Medicare for All and the Green New Deal. The party’s most popular young star, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, is an avowed socialist. Democrats, by a 10-point margin, now think that socialism is more appealing than capitalism, and that’s significantly more true of people under 30. Polling has even suggested that 70 percent of the country supports Medicare for All, including a majority of Republicans.

Trump’s strategy is commonplace in partisan politics: to define the opposing party by its most extreme members. As The New York Times reported on Wednesday, focusing on socialism “could provide Mr. Trump with a potentially effective weapon in confronting an increasingly aggressive and more liberal Democratic Party, defining it through attacks on Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, who describe themselves as democratic socialists, and other members of the party pushing progressive policies like a 70 percent tax rate and ‘Medicare for all.’”

There is historical evidence that Trump’s strategy could work, as red-baiting has been an often effective tool for conservative politicians over the past century. The question is whether that remains true today. As the Times acknowledged, “there is no evidence of any growing public angst about socialism sweeping the United States.” It’s true that Americans broadly see social programs like Medicare for All in a much better light than they do socialism itself. One August NBC/WSJ poll, though something of an outlier, found that only 19 percent of voters viewed socialism positively. Then again, Sanders may end up as the only Democratic candidate for president who defines himself thus.

The bigger flaw in Trump’s anti-socialism strategy, though, is that it’s forcing him to be staunchly pro-capitalism at a time when its popularity is severely ebbing. In doing so, Trump is forgetting one of the most important lessons of his 2016 victory. Hillary Clinton made the case that the economy was strong and that Democratic stewardship over it should continue. Trump railed against a “rigged” system that had decimated rural and Rust Belt communities, and he vowed to fix it. This message, combined with his pledge to protect entitlements like Medicare and Social Security, was vital to his upset victory—helping him to win key the states of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. (His approval is now underwater in all three states by double digits.)

Today, Trump is not only embracing the “rigged” system, but further owning his own unpopular economic policies, notably the $1.5 trillion tax cut he signed into law in December of 2017, which largely benefitted corporations and rich Americans. In the State of the Union, Trump boasted that “we are considered far and away the hottest economy anywhere in the world.” But many Americans still aren’t feeling that heat, just as they weren’t in 2016. Most of the economic gains have gone to the top 20 percent, and wage growth, while ticking upward over the past six months, has been largely flat throughout most of the economic recovery. This, much more than Sanders, is why more Americans have warmed to socialism. “The prime mover of millions of Americans into the socialist column has been the near complete dysfunctionality of contemporary American capitalism,” argued Harold Meyerson in The Guardian.

That’s not to say that Trump’s strategy won’t yield any benefits for him. Howard Schultz, the former Starbucks CEO contemplating an independent run, has already discerned that dividing the Democratic Party is the best path to victory. The response to Trump’s attacks on socialism has been relatively quiet on the left thus far, but the Democratic Socialists of America did release a statement on Tuesday decrying Speaker Nancy Pelosi for tepidly applauding. “Nancy Pelosi clapping at Trump’s remark about socialism, while children in Flint drink poisoned water, tens of thousands die for lack of health insurance every year, and we are headed off a climate cliff because big oil refuses to give up their profits. is peak capitalism,” the statement read. “The American People will not stand for it.”

But any such infighting on the left is likely to be semantic and largely forgotten once Democrats nominate a candidate. We can fairly predict that the nominee will support universal health care, taxes on the rich, economic reform, and an infrastructure stimulus—all policies that will appeal to the millions of Americans who have been left behind by the economic recovery, and who fear they’ll fall even further behind when the economy inevitably turns for the worse. Trump, by contrast, will be shouting “better dead than red” and insisting that the economy is the greatest, ever. He thinks he set a trap for Democrats with his State of the Union jab, but in reality he has just trapped himself.

Alexander Gauland is a one-man Godwin’s Law. He has warned of an “invasion of foreigners,” argued a German minister should be “disposed of” in Turkey, and echoed an address Hitler gave in 1933 by writing a column attacking members of the “globalized class,” or “rootless, international clique.”

He is also the moderate face of the Alternative for Germany (AfD)–the country’s anti-migrant right and, since 2017, its largest opposition party in parliament. Since its 2013 founding, the party has struggled to move past the Sieg Heil crowd and simple xenophobia that tends to accrue to its official euroskeptic platform. Last month, at the party’s conference in Riesa, Saxony, co-leader Gauland went a step further, discarding even the most recent party manifesto’s calls for “Dexit” (a German Brexit). The result, however, has been a schism, the more rabid party members splitting to form a more reliably extremist corps. At a moment when the party seeks to build a transnational right-wing alliance ahead of European Parliament elections in May, these internal politics could have an outsized effect on the trajectory of Europe’s resurgent right.

Gauland distilled the AfD’s new tone into a 20-minute speech in Riesa last month, where sporting his signature tweed, he delivered a typical takedown of Brussels “paternalism.” The bloc’s 28 nations are “squeezed into a corset,” Gauland said, meandering through nationalist references to Nietzsche, Franz Josef Strauss, and Otto von Bismarck. He compared the EU to Hitler—a guaranteed crowd-pleaser, in short, from a party whose foundation was predicated on the abolishment of the Euro. But in a new move, Gauland also questioned the party manifesto’s call for an exit from the bloc altogether by 2024, should its immigration demands be ignored. “Whoever plays with the idea of Dexit must ask,” he said: “Isn’t that a Utopia? And shouldn’t we be realistic?”

Germans are overwhelmingly pro-EU: a May 2018 poll found 79 percent would vote to remain in the bloc if given a British-style referendum. Even in Saxony, the AfD’s former-East German stronghold, a huge majority would oppose Dexit. But Gauland’s speech reflected more than political pragmatism. It marked an apex in a growing fight for control of the AfD, between Gauland’s so-called moderates and a more radical wing of the party, led by Björn Höcke, a Thuringian statesman who has publicly denounced Berlin’s Holocaust memorial as a “monument of shame” and has advocated for a “180-degree turn” in attitudes to the Second World War. In 2016, Höcke came under fire for a speech in the city of Erfurt, in which he demanded Angela Merkel be “removed from the Chancellory in a straitjacket” for her open-door policy on immigration.

The day after Gauland’s speech, André Poggenburg, a close Höcke ally, quit the AfD to form his own Aufbruch der Deutschen Patrioten (Awakening of German Patriots). Right-wing schisms are a staple of conservatism: There are the libertarian, hands-off-my-money types, and then there are the cultural right-wingers, tired of watering down their racism to win votes. Poggenburg seems to be the latter. His new party takes for its emblem the blue cornflower, a symbol of 1930s Austrian Nazism—and as political choices go, less of a dog whistle than a foghorn. Soon after this news broke, Germany’s domestic intelligence agency announced it would be monitoring AfD activities—with special attention to the more radical elements including Höcke’s wing, commonly called Der Flügel (“The Wing”)—for potential breaches of the German constitution.

Höcke and Poggenburg’s extremism could stymie the AfD’s electoral progress altogether. Even by splitting the vote a little they would stand to forfeit a fair chunk of the AfD’s 12.6 percent share won at the last federal race in 2017, pushing the far-right parties numerically closer to more established parties like the center-right FDP (10.7 percent), democratic socialist The Left (9.2 percent) and even the resurgent leftwing Greens (8.9 percent), whose euro-friendly tone has struck a chord with young voters dismayed at rightward turns across the continent.

But the main branch of the AfD seems disinclined to win the extremists back. On February 2, Gauland’s co-chair Alice Weidel addressed a crowd in historic Karlsruhe, doubling down on the party’s new, more living-room friendly message. Weidel, an economist who has come under fire for receiving election funds from Switzerland, and in 2013 sent an email in which she denounced the takeover of Germany by “Arabs, Sinti and Roma,” this time stood behind a poster saying “Rethinking Europe,” and justified her party’s opposition to Brussels in terms of margins and bottom lines, rather than the race-based screeds that have accompanied the AfD’s rise thus far. Weidel even paraphrased Wilhelm Röpke, a famous anti-Nazi protester and architect of the postwar Wirtschaftswunder, or “Economic Miracle,” when slamming Europe’s “centrist betrayal.”

The new moderation seems to be a change in focus, rather than ideology itself. As calling for a German EU exit looks ever more politically suicidal–especially given the economic and political turmoil consuming Britain ahead of its presumed EU curtain call this year—AfD leaders seem to be seeking another way to advance the euroskeptic cause. Fellow right-wingers across Europe, who want to reform the bloc under Marine Le Pen’s “Europe of Nations” alliance, offer one solution. Another AfD co-chair, Jörg Meuthen, has echoed the “Europe of nations” language in recent weeks, and Gauland called the crowd before him in Riesa “good Europeans … heirs of millennia of the European spirit.”

If the AfD wins big in May, expect the party to play kingmaker in a new axis of euroskepticism, alongside populists in Poland, Hungary, France, Italy, Austria and elsewhere. For all its more moderate rhetoric, this new transnationalism is of a narrow sort, aimed at banding together within Europe to give supporters what they’ve wanted all along: closed borders and minimal immigration, particularly from non-European countries. Whether the cornflower-wearing, racist underbelly of the AfD balks at such a strategic move and sabotages it in the name of ideological purity remains to be seen.

Two years ago, two Stanford professors teamed up with a journalist to survey more than 600 “elite technology company leaders and founders” about their political views. The average executive, they found, believes in free markets, supports gay marriage, likes environmental protection, hates unions, and distrusts regulation. He says he wants higher taxes to fund social programs, but he’d prefer it if entrepreneurs ran such programs instead of the government. (This may explain his fondness for charter schools.) Countless newspaper or magazine profiles have described his lifestyle. He microdoses LSD. Each year, he travels to Burning Man. He may well have attended the Women’s March or protested the Muslim ban. These, we often hear, are the politics of Silicon Valley—a distinctive mix of liberalism and libertarianism.

Decades ago, two British media theorists came up with a term that encapsulates this set of views: “the Californian Ideology.” In an influential essay first published in 1995, Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron described the politics of Silicon Valley as a synthesis of socially liberal attitudes inherited from the Bay Area counterculture with “an anti-statist gospel of cybernetic libertarianism.” The philosophy “promiscuously combines the free-wheeling spirit of the hippies and the entrepreneurial zeal of the yuppies,” Barbrook and Cameron wrote, while mixing “the social liberalism of New Left and the economic liberalism of New Right.” It’s why Wired magazine could run a flattering interview with Newt Gingrich on its cover.

Since the 2016 election, politicians and pundits have begun to question the longstanding assumption that the internet is always and everywhere a force for good. But the “tech backlash” has yet to overturn another assumption: that the Californian Ideology still governs the tech industry as a whole. The upper rungs still clearly subscribe to its tenets. Yet those tenets are nowhere near as dominant among the workers who make up the majority. And a failure to differentiate the people who own the industry from the people who work in it is causing the media to misread the rising wave of rank-and-file rebellion.

Employees at companies like Google and Amazon are challenging their employers to drop contracts with the Pentagon, ICE, and other government agencies. They are organizing for workplaces free from sexual harassment and discrimination. They are demanding better wages, benefits, and working conditions for the contractors who supply much of the labor that makes the industry run.

As they do, they are invoking a very different language than their bosses are. Indeed, they are creating a whole new paradigm.

In their essay on the Californian Ideology, Barbrook and Cameron described the people who worked in Silicon Valley as “digital artisans.” Today they are more likely to be called “entrepreneurs” or “creatives,” but the idea remains the same: engineers, designers, and product managers are driven by passion and purpose. As Steve Jobs exhorted them, they do what they love.

Lately, however, this cohort has begun to talk about themselves in a different way, as “tech workers.” Popularized by organizations like the Tech Workers Coalition—which was cofounded in San Francisco in 2014 by a labor organizer and a software engineer—the term challenges the Californian Ideology at several levels. As we usually understand them, workers are not “creatives,” inspired by a higher calling. Most people are workers by necessity, and sell their labor to make a living. By calling themselves workers, members of the new movement are staking a claim to this common identity.

This common identity, in turn, has enabled tech workers to build alliances across roles with the shuttle drivers, security guards, janitors, and cafeteria staff who make up the industry’s “invisible workforce.” In 2017, food service workers at Facebook voted to unionize after white-collar employees distributed materials on campus, did house-to-house visits, and asked pointed questions at “all hands” meetings. The recent Google walkout—which saw 20,000 people stop work in offices all over the world—also involved both full-time and contract employees. In the months since, the organizers have demanded better wages and benefits for the contractors, who make up more than half of Google’s workforce.

If elite paternalism is the preferred mode of Silicon Valley leaders—evident in their belief that people like them should run social programs—tech workers are taking a different tack. While they recognize that different kinds of workers wield different levels of power within a company, they are forging relationships around what binds them rather than what does not.

As Stephanie Parker, one of the organizers of the Google walkout, explained to Wired, “Seeing the cafeteria workers and security guards at Silicon Valley companies bravely demand access to benefits and respect was a deeply inspiring experience.” The tech worker movement has also drawn inspiration from organizing in other sectors. Leaders of the Google walkout hailed as a model protests by McDonald’s workers against sexual harassment. A Google worker who helped lead the anti-Pentagon campaign last year cited the influence of ongoing teacher strikes: “It’s time for us to join the new labor movement,” the worker told Jacobin.

Tech workers are also claiming greater control over their work—control that the Californian Ideology suggested they should have already, but which recent confrontations with their bosses have made clear they do not. At Amazon, employees have petitioned CEO Jeff Bezos for “a choice in what [they] build, and a say in how it is used.” At Google, they have demanded “a say in decisions that affect their lives and the world around them.” To that end, Google organizers want to create a seat for a worker representative on the board, as companies regularly do in many European countries.

These members of the new tech worker movement don’t sound like the “hippie yuppies” of the Californian Ideology. They are embracing a more collective, worker-driven politics—one that owes less to Ayn Rand than it does to Eugene Debs.

Until recently, media outlets have failed to register this shift, because they have let tech executives speak for the industry as a whole. A piece in The New York Times, based on the Stanford study cited above, purported to express the views of “Silicon Valley.” In the twelfth paragraph, the author revealed that “Silicon Valley” meant executives. It’s roughly equivalent to interviewing a handful of Wall Street hedge fund managers and claiming the results speak for New York.

Several journalists have skillfully reported on the tech worker actions. But their colleagues in the opinion pages have mostly failed to understand these actions’ nature and significance. In The New York Times, Susan Fowler wondered whether the campaigns against the Pentagon and other government agencies reflected “Silicon Valley’s strong libertarian leanings.” An editorial in The Wall Street Journal condemned “the rise of campus-style political activism among Silicon Valley employees.”

These analyses fail to register that the tech worker movements are creating a new paradigm—a paradigm that breaks with the mix of libertarian anti-statism and hippie-inflected liberalism that continues to dominate tech’s leadership class. The leaders of the tech worker movement are making a new and paradoxical gambit—that by claiming a common identity as workers, they can exercise their special power. Rather than waiting to be saved by CEOs, they are threatening the profit engine. They are betting that when tech workers who are expensive to hire and train join in collective action, CEOs must pay attention.

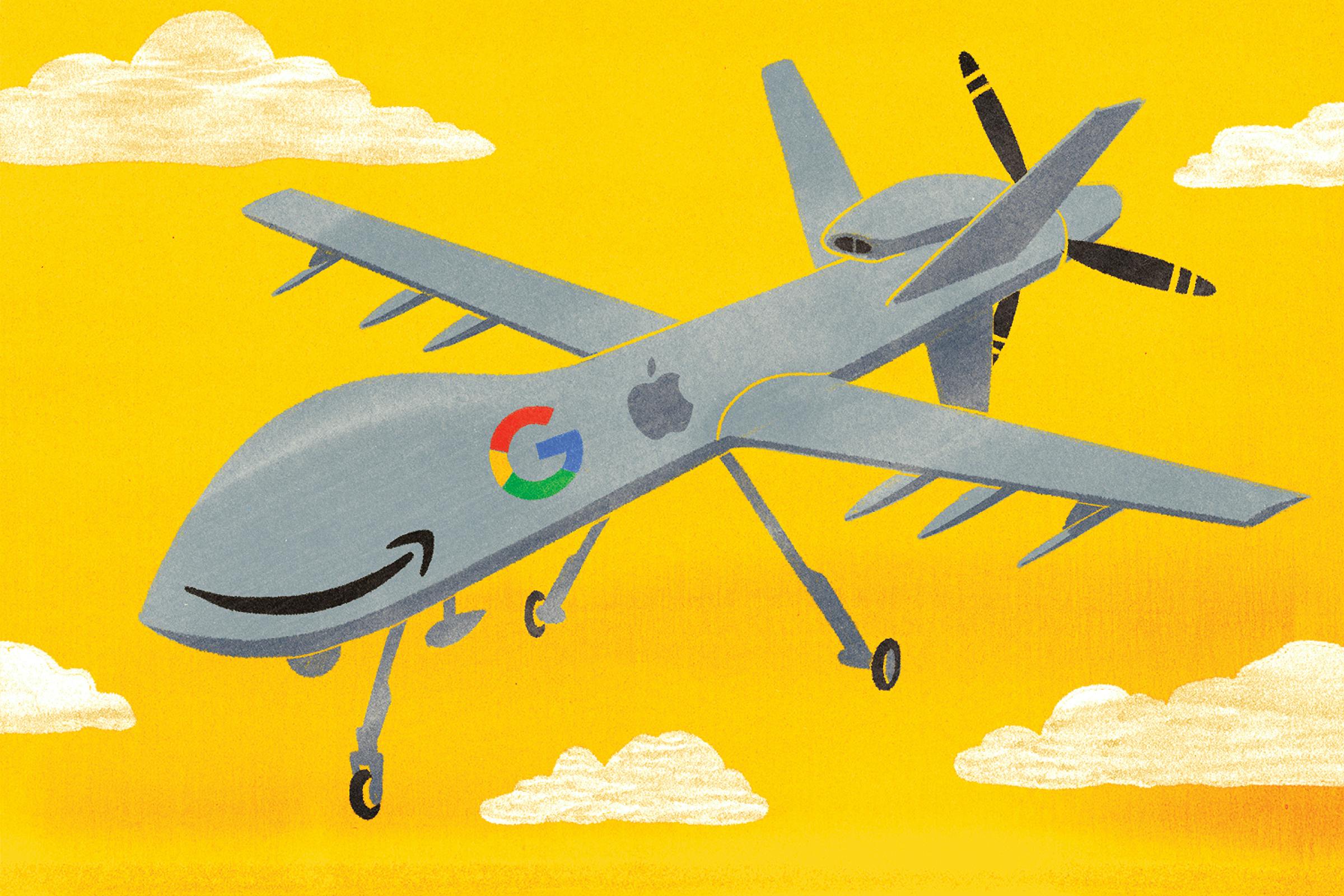

In September 2017, Google began work on Project Maven, a Pentagon program that provides artificial intelligence software for drone warfare. More than ten employees were tasked with building a highly realistic surveillance system, like Google Earth, that would render whole cities and buildings, classifying cars as cars and people as people, and allowing the Pentagon to pinpoint both with near precision, in real time, from the skies. Less than a year in, some of the engineers started developing doubts about the project. By February, questions were circulating on Google’s internal communications channels, and soon almost 4,000 employees had signed a petition calling on the company to cancel the contract. “Google,” they wrote, “should not be in the business of war.” In May, a dozen resigned. “It’s one thing for the military to have its own engineers,” a Google employee told me. “It’s another thing for the private sector to build this technology and profit off death.”

.march-cover-button { background: white; max-width: 250px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; line-height: 1.4; border-bottom: 6px solid #00bfd8; padding-bottom: 20px; } .march-cover-button-header { border-top: 6px solid #00bfd8; border-bottom: 2px solid #00bfd8; color: black; padding-bottom: 10px; } .march-cover-button-header h2 { margin-top: 15px; font-size: 130% !important; } @media screen and (min-width:640px) { .march-cover-button { margin: 0 -50px 2em 2em; float: right; } } .march-cover-button img { -webkit-transform: scale(1); transform: scale(1); -webkit-transition: 0.8s ease-in-out; transition: 0.8s ease-in-out; } .march-cover-button a:hover img { -webkit-transform: scale(1.05); transform: scale(1.05); } .march-cover-button a { background: none !important; text-shadow: none !important; display: block; margin-bottom: 20px; } .march-cover-button a:last-child { margin-bottom: 0; } .march-cover-button-info h3 { font-size: 110% !important; margin-top: 10px; } .march-cover-button-info h4 { font-size: 100% !important; margin-top: 0; font-weight: 500; }Google, of course, is far from the only tech company to take on military contracts. Apple is currently one of a consortium of companies and universities developing “stretchable” electronic sensors to monitor troops and ships; Amazon provides servers, storage, databases, software, and analytics to the CIA through the cloud; Dell licenses software to ICE.

The companies tend to describe such work in overtly patriotic language. In October, Microsoft’s president, Brad Smith, wrote, “We believe in the strong defense of the United States and we want the people who defend it to have access to the nation’s best technology, including from Microsoft.” Jeff Bezos had said much the same only a few days before: “This is a great country, and it does need to be defended.” He was facing dissent at his own company over Rekognition, Amazon’s facial recognition software. Yet as organizers have pointed out, the technology, which can identify and track “persons of interest” in crowded events, is less likely to be used to “defend” the United States than to track down people who themselves need defending. This summer, Amazon was pitching the program to ICE officials, raising concerns that it might be used to target undocumented immigrants.

The tech industry’s relationship with the military dates to the earliest days of computers. In World War II, the United States used IBM’s punch card technology to process detainees in Japanese internment camps. (The Nazis used it, too—something organizers have been keen to mention.) During the Cold War, the United States used Fairchild Semiconductor’s chips in ballistic missiles. ARPA—the Pentagon’s advanced research agency—funded the early internet’s development in the 1960s. Half a century later, its research has made Siri possible, and provided the interface for most Windows laptops. In certain cases, the links between tech and the Pentagon are quite personal. As Leslie Berlin recounts in her book Troublemakers, Steve Jobs saw as mentors some of the early semiconducting pioneers, who had worked with the government during the Cold War. Bezos’s grandfather worked for ARPA.

The long-running intimacy between tech and the Defense Department has not gone unchallenged. In the 1970s, for example, Computer People for Peace protested the Vietnam War from within Silicon Valley, targeting Honeywell Aerospace for manufacturing fragmentation bombs augmented to kill humans, and IBM for what the activists called “corporate racism.” (The company was trying to expand its business into apartheid South Africa.) But Computer People for Peace only ever had a few hundred members. It is hard not to feel that tech’s complicity with the military is too deep to be undone, the ties too strong to be broken. And it’s difficult to predict the prospects of this nascent opposition. Some of the movement’s energy may result from having an antagonist in the White House. “When you’re watching the news and seeing family separation at the border and realize your company works with ICE, that doesn’t feel good,” one woman, who used to organize the tech sector, told me. If a Democratic president takes office, or these images go away, it seems at least conceivable that the walkouts, protests, and petitions will disappear, too.

But at least one organizer I spoke to (on condition of anonymity) did not think so. “If Trump got impeached tomorrow,” the Google employee told me, “we’re not going anywhere.” His efforts would outlast Trump, he believed, because Trump was not their sole object. A Democratic president will also use technology to wage war on other nations and police our own. As the Google worker cast it, the opposition is to state violence broadly conceived, not merely a particular defense contract at a particular company. Some of the efforts aren’t even focused on American policies; Google employees have, for instance, objected to Chinese censorship.

More likely than the possibility of losing momentum after Trump is gone is the possibility that some of the first organizers will leave their companies for different ventures. At Google, some have already resigned in protest, and more could follow; in Silicon Valley, engineers change jobs frequently. A strong union might once have funneled new leaders in behind the first generation, but the organizing against state-sponsored violence has happened on its own. Still, strong internal networks are forming within these companies, along with groups like Tech Workers Coalition, Tech Action, and Tech Solidarity, which are springing up across the country to call protests, hold meetings, and build up a leadership pipeline. These groups offer the beginnings of a kind of infrastructure that unions provide in other industries. Should momentum continue to build, they might even be in a position to organize a strike. In an industry where talent is scarce, strikes could cripple operations.

Company executives will never voluntarily forgo profits. Even as Google was conceding on Project Maven, praising its employees publicly for working to “create a better workplace,” in private the company was urging the government to narrow legal protections for workers’ organizing. If Google gets its way, it could legally punish anyone who used company email to organize protests, circulate petitions, or form a union. (Google told Bloomberg in January that the limitations were floated as just one possible strategy in a legal brief filed to the National Labor Relations Board.) Even so, what organizers have already been able to achieve is significant, and the tech industry as a whole is so powerful that its choices reverberate loudly. A strong internal revolt may lead, eventually, to policy changes on questions of war and surveillance. A few years from now, engineers may be organizing with those who work the supply lines, from warehouses to the cobalt mines of the Global South, and with those directly touched by the implacable force of the state.

Companies in Silicon Valley are wonderfully fond of describing themselves as “mission-driven.” Palantir has raised nearly $2 billion “working for the common good” and “doing what’s right.” At Theranos, Elizabeth Holmes promised “actionable information at the time it matters.” And for the past four years, Google and Facebook have occupied top spots on Business Insider’s annual list of the “Best Places to Work,” not merely because they dispense such perks as free laundry and subsidized dental care, but also because they claim to offer their workers the chance to be part of a meaningful project of global scope.

.march-cover-button { background: white; max-width: 250px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; line-height: 1.4; border-bottom: 6px solid #00bfd8; padding-bottom: 20px; } .march-cover-button-header { border-top: 6px solid #00bfd8; border-bottom: 2px solid #00bfd8; color: black; padding-bottom: 10px; } .march-cover-button-header h2 { margin-top: 15px; font-size: 130% !important; } @media screen and (min-width:640px) { .march-cover-button { margin: 0 -50px 2em 2em; float: right; } } .march-cover-button img { -webkit-transform: scale(1); transform: scale(1); -webkit-transition: 0.8s ease-in-out; transition: 0.8s ease-in-out; } .march-cover-button a:hover img { -webkit-transform: scale(1.05); transform: scale(1.05); } .march-cover-button a { background: none !important; text-shadow: none !important; display: block; margin-bottom: 20px; } .march-cover-button a:last-child { margin-bottom: 0; } .march-cover-button-info h3 { font-size: 110% !important; margin-top: 10px; } .march-cover-button-info h4 { font-size: 100% !important; margin-top: 0; font-weight: 500; }In that sense, mission statements are as much directed internally, at employees, as they are externally, at the public. The hours may be long and the competition fierce, the implicit message goes, but it’s worth it because the reward is spiritual as well as tangible. At some tech companies, faith in the mission is encouraged to the point that it resembles religious belief. Employees are invited to see themselves as proselytizers for the transformation of society, spreading the ideas of a company and its leaders around the world.

What happens, though, when the mission doesn’t accord with the behavior of a company or the values of its employees? For many, it has become increasingly impossible to believe that tech firms are working disinterestedly in service of some larger social good. Employees at Google have staged walkouts to protest sexual harassment and petitioned the company to halt its plans to develop a search engine that supports Chinese government censorship. Workers at both Google and Microsoft spoke out against providing cloud services for the Department of Defense, and Amazon employees posted an internal letter protesting how Amazon Web Services provides facial recognition technology to police.

These debates often pivoted around the companies’ mission statements. At Amazon, one organizer wrote, “Selling this system runs counter to Amazon’s stated values. We tout ourselves as a customer-centric company, and [chief executive Jeff] Bezos has directly spoken out against unethical government policies that target immigrants, like the Muslim ban. We cannot profit from a subset of powerful customers at the expense of our communities.”

Like many tech CEOs of the current era, Bezos counted on his mission statement inspiring and lifting up his employees with the sense that they were transforming the world for the better. What the protests make apparent, however, is that it also instilled in them a sense of responsibility, even guilt. Bezos is learning what many tech executives have learned over the past year: that a mission statement only commands loyalty when employees believe it is being consistently upheld; that when they see that it isn’t, they will use it as reason to foment dissent, to strike, to leave.

Google’s ideals were famously articulated in the 2000s with the shorthand “Don’t be evil” (those three words appear in Google’s 2004 IPO filing), but its stated mission, first laid out by founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page in 1998, is far more concrete: to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” In 2014, Page considered revising this formulation of the company’s goals. After all, Google was no longer just “organizing the world’s information”; it had expanded its operations into self-driving cars and experiments in biotechnology. But Page decided against a change, and that original mission statement has come to haunt them.

“Employees at Google have been fairly vocal about making sure that the company upholds its pledge to not be evil,” Liz Fong-Jones, an engineer on Google’s Cloud Platform, told Fast Company last year. In 2016, she was among 2,800 tech workers at Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and other companies who signed a pledge not to work on software that assisted discriminatory policies like President Donald Trump’s Muslim ban. When news broke last year that Google was planning to create a censored search engine called Dragonfly for use in China, they once again criticized the company for failing to live up to its values. How was a censored search engine, they asked, making information “universally accessible”?

“Our mission is to serve everyone,” Google’s CEO Sundar Pichai said at an event in November. His explanation was a subtle but profound redescription of Google’s stated goals. According to him, the point was not to make information “universally accessible,” but to make Google itself universally available, even if the information it provides is censored. What Pichai was doing wasn’t unusual. Corporate mission statements are cooked up in C-suites, and CEOs can—and often do—change how they are interpreted. Perhaps predictably, though, Pichai’s comments failed to placate his employees, and protests over Dragonfly continued. Google was finding out what it meant to possess a mission with real content, one that isn’t full of “bizspeak and bromides,” as a 2007 New York Times article described the vast majority of statements. The more technical the mission, the more likely it can be wielded as a tool to organize employees against leadership.

In its early years, Facebook articulated its goals in much the same way as Google. At an event for developers in 2007, Mark Zuckerberg spoke of wanting to “help users share more information,” a phrase that echoed Google’s aims of making information “accessible to everyone.” But whereas Google’s language remained the same over the years, Facebook’s evolved to become more communally and socially oriented. In 2009, Facebook’s goal was to “make the world more open and connected,” but by 2017, the company had changed it to giving people “the power to build community and bring the world closer together.”

This might seem like it would be an ideal mission to facilitate organizing. Yet it mattered how the company defined community. “Bringing the world closer together” often meant, in practice, fostering networks that increased conformity. In the rare instances when full-time Facebook employees have spoken out publicly, there have been repercussions. Last spring, Brian Acton, the cofounder of WhatsApp, resigned. A few months later, he gave an interview to Forbes detailing his philosophical differences with company. That day, a Facebook executive wrote a public post calling him “low-class” for finding fault with a company that had “shield[ed] and accommodate[d]” him for years.

The working atmosphere at Facebook—where the product one labors on is also where one socializes with colleagues, friends, and family—is designed to enforce fealty to the mission and, like the product itself, to facilitate the goal of absolute togetherness. In January, CNBC ran an article about what it called Facebook’s “‘cult-like’ workplace.” “There’s a real culture of ‘Even if you are f---ing miserable, you need to act like you love this place,’” one former employee, who left in October, told the network. “It is not OK to act like this is not the best place to work.” Some of those who want to have critical discussions have purchased burner phones, so their comments wouldn’t get back to their managers. Most of the dissent that has been voiced publicly was channeled through anonymous leaks to journalists, not visible protest. And the collective organizing that has happened at Facebook has occurred among contract workers, who don’t enjoy the generous benefits of full-time employees and aren’t subject to the same intra-office cultural pressures.

The Times article suggested that most mission statements aren’t “worth the paper they were written on”—so insubstantial and formulaic that they may as well be computer-generated. Recent events suggest why it’s in executives’ interest to keep them that way: Concrete mission statements assist employees in making concrete demands. Tech companies may be doing everything they can to convince their employees that their labor has a higher purpose, but their workers know better. These companies are still corporations, and their employees are still in the business of turning them a profit.

As in so many cases of sexual harassment, it was not the incident that sparked the most outrage, but the employer’s response.

In 2012, Andy Rubin, the Google executive who developed the Android operating systems, started dating a woman who worked for him. By 2013, she wanted to end the affair. When she agreed to meet him in a hotel room, she later reported, he coerced her into performing oral sex. Google investigated the incident, found her complaint credible, and in 2014, the company’s CEO, Larry Page, demanded Rubin’s resignation, but not without softening the blow. “I want to wish Andy all the best with what’s next,” Page told employees. “With Android, he created something truly remarkable.” Over the next four years, the company paid Rubin $90 million in severance and invested millions in his new venture capital firm.

When The New York Times published the details of Rubin’s case this past October, more than 1,500 Google employees took to a company mailing list to coordinate a worldwide walkout in protest. They expected a small gathering, but on November 1, more than a fifth of Google’s global workforce, 20,000 people in all, exited their offices, carrying signs that read “Hey Google, WTF?” and “Happy to quit for $90m—No sexual harassment required.”

Four months later, the walkout appears as just one indication of a growing rift between labor and management in Silicon Valley. Tech CEOs like to think of their companies as open, horizontal organizations that reject entrenched bureaucracy and corporate hierarchies. But as they scale up from freewheeling startups to industry giants, that dynamic has been altered. Now, tech executives run their growing empires from seemingly distant corporate suites, and workers are demanding a greater say in how decisions are made and policies crafted. As one person put it in a speech during the walkout, “Google is not one human being ... who gets to hold all the power. It’s every single person who shows up to work every single day.”

.march-cover-button { background: white; max-width: 250px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; line-height: 1.4; border-bottom: 6px solid #00bfd8; padding-bottom: 20px; } .march-cover-button-header { border-top: 6px solid #00bfd8; border-bottom: 2px solid #00bfd8; color: black; padding-bottom: 10px; } .march-cover-button-header h2 { margin-top: 15px; font-size: 130% !important; } @media screen and (min-width:640px) { .march-cover-button { margin: 0 -50px 2em 2em; float: right; } } .march-cover-button img { -webkit-transform: scale(1); transform: scale(1); -webkit-transition: 0.8s ease-in-out; transition: 0.8s ease-in-out; } .march-cover-button a:hover img { -webkit-transform: scale(1.05); transform: scale(1.05); } .march-cover-button a { background: none !important; text-shadow: none !important; display: block; margin-bottom: 20px; } .march-cover-button a:last-child { margin-bottom: 0; } .march-cover-button-info h3 { font-size: 110% !important; margin-top: 10px; } .march-cover-button-info h4 { font-size: 100% !important; margin-top: 0; font-weight: 500; }To appease their employees, firms are drawing on ideas from an old-fashioned bureaucratic tool kit, adopting the kind of human resource policies they once eschewed in an attempt to impose a layer of accountability between employees and their managers. In November, Google’s CEO, Sundar Pichai, announced that the company would implement new harassment reporting processes and place a greater emphasis on harassment training. Yet the history of HR is one of unanticipated consequences and backlash effects. Policies like the ones Google is putting in place may be ineffective at best, and at worst may entrench gender inequality.

This has something to do with the origins of the human resource department, which was born not out of beneficence but from companies’ need to defend themselves against ambiguous employment laws. When Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibited employers from discriminating on the basis of race, religion, sex, and national origin, the federal government offered no definition of discrimination. Employers were left to define practices to keep abreast of rapidly expanding employment protections and ensure that they were compliant. These practices were given their own departments. Over time, the departments took on a life of their own, as so many things do in organizations. With annual reports, official procedures, and physical office space, the existence of a division becomes taken for granted—rarely evaluated in terms of its intended purpose. Sociologists Frank Dobbin and John Sutton identify these developments as evidence of the surprising strength of a “weak state”: When the state leaves the laws fuzzy, firms dedicate substantial resources to designing programs that demonstrate compliance. At the behest of management, many HR policies are designed in this spirit, with little regard for whether they instigate substantive improvements for employees.

The discontent at Google is about more than a single incident. It is a reaction to the persistent problems of diversity and inclusion both at Google and across Silicon Valley. Today, Google is less than 3 percent black, less than 4 percent Latinx, and only 31 percent female (a number that has risen a mere 0.3 percent since 2014, even though Google spent $265 million on diversity initiatives that year and the next). The lack of representation spills over into pay inequality. Google claims to have no pay gap, compensating everyone equally based on their job title and experience, but in 2017, the Department of Labor concluded that there are, in fact, “systemic compensation disparities against women pretty much across the entire workforce.”

To remedy these problems, the team that organized the walkout submitted a list of five demands. They asked the company to commit to equality of pay and opportunity. The rest of their demands are aimed at curbing the abuse of power—with a safe and anonymous harassment reporting procedure, increased corporate transparency around harassment, and an end to forced arbitration in harassment cases, which often advantages the company over complainants.

Google replied with apologies and proposed changes that address each of the five demands. It has promised to end forced arbitration in sexual harassment cases and allow bystanders to participate in the reporting process—both changes that will make a substantial difference to people reporting harassment. When it comes to preventing harassment, however, Google is relying on better education about harassment policies and more frequent harassment trainings. These practices are used almost universally across industries. But they often don’t work.

Simply reading a sexual harassment policy can lower people’s opinions about women and reinforce implicit beliefs that favor men. This reaction may result from how policies are worded, typically portraying men as powerful and women as vulnerable. Studies show that they make people more likely to believe that women are irrational and men are vulnerable to false accusations—precisely the opposite of the intended effect.

Harassment training—which has been almost universal in American firms since 1998, when two Supreme Court decisions shielded companies from liability if they trained their employees on the sexual harassment policy—also tends to be unproductive. Studies rarely show participants leaving with a better understanding of harassment. Trainings can even backfire. Some researchers have suggested that men perceive the lessons as accusatory and grow defensive, becoming less capable of correctly identifying the behaviors that constitute the problem. The men most likely to harass—the ones who score highest on what researchers call “gender-role conflict” tendencies—have the most adverse reactions to training.

Google—along with the tech industry more broadly—has made little progress on solving these dilemmas.The new policies the company announced in November are entrenching the flawed systems. Harassment training will now be required every year, instead of every two, and workers who don’t attend trainings will have their performance scores docked—from “exceeds expectations,” for instance, to “consistently meets expectations.”

While Google has promised to improve its process for reporting harassment, its assurances are unlikely to alter the gender imbalances that deter women from coming forward in the first place. According to a 2018 survey, 41 percent of tech professionals who report an incident of any kind to HR experience some form of retaliation, from hostile comments to low performance scores or dismissal. Even once Google has made it easier to report harassment, women at the company will still confront a wrenching choice: say something and risk everything, or say nothing and let the harasser off the hook.

Over the past year, conservative commentators have said time and again that the activism stemming from the #MeToo movement may backfire on women; men, they have warned, will avoid working closely with their female colleagues for fear of crossing a boundary into inappropriate intimacy. The more likely but less discussed risk is that organizations will try in good faith to educate their workforces about sexual harassment—only to have those efforts hurt the very people they’re meant to protect.

If Google hopes to achieve the cultural changes demanded by its employees, the answer is plain. Firms with larger percentages of women in core roles and management positions consistently have lower rates of harassment. It’s not clear whether that’s because seeing women in power changes employees’ unconscious beliefs about gender or because the women in charge create more equitable environments. But the research is emphatic on one point: Hiring and promoting women is the most reliably effective way to reduce harassment.

Firms with larger percentages of women in core roles and management positions consistently have lower rates of harassment.This is no simple intervention. It takes years to place women in C-suites and fields like engineering, which remain dominated by men. It also requires fundamental changes to the processes by which people are invited into organizations and moved around them. Managers need to be held accountable for the evaluations they use to make their decisions about who to hire and who to promote, and the very skills and characteristics associated with good leadership need to be rethought.

Only with women in positions of power can companies expect to level the structural imbalances that have allowed men to use their status to manipulate less powerful employees—and bargain for extravagant severance packages when they are caught.

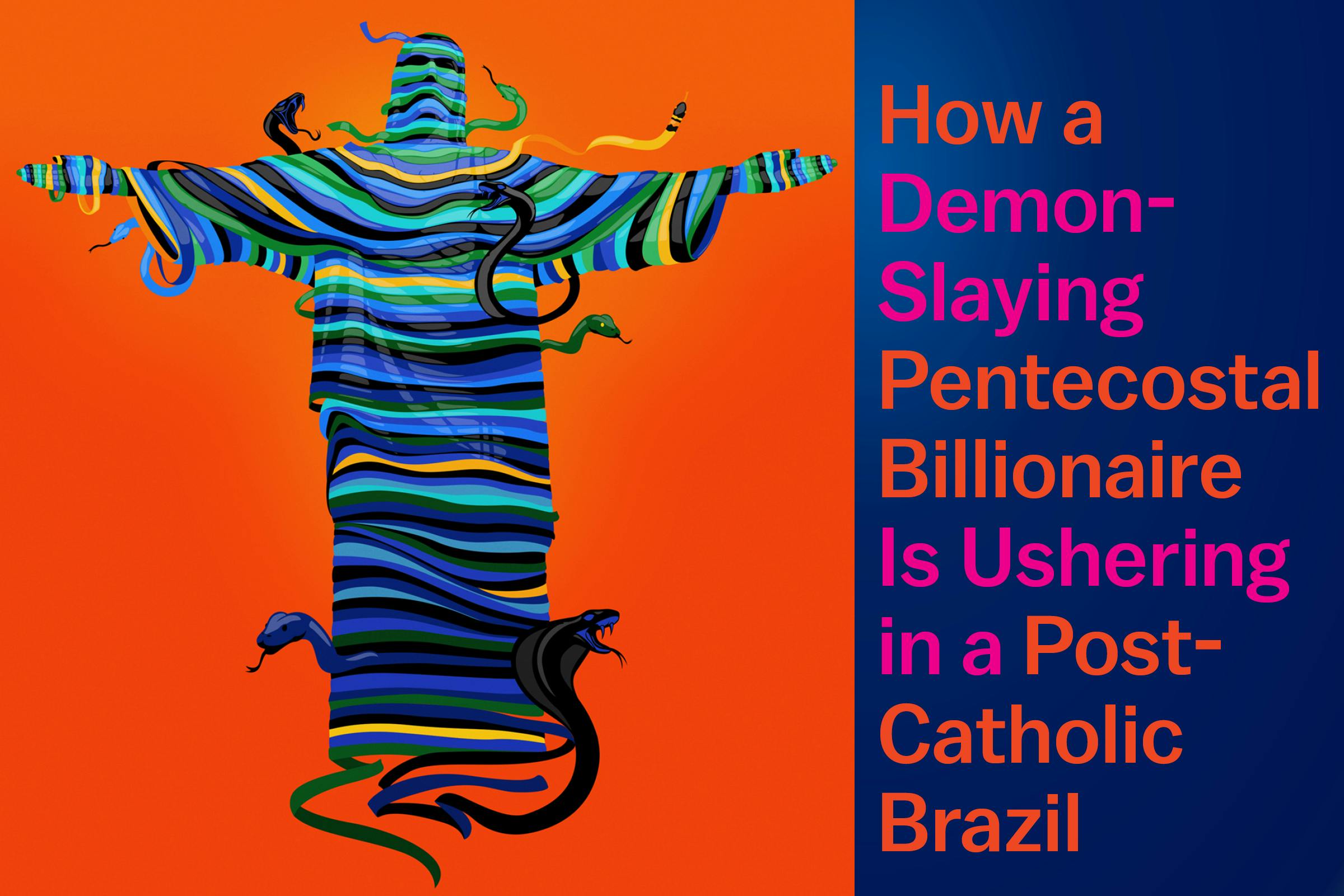

The headquarters of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God does not resemble your typical megachurch. Its eighteen stories dwarf the big-boxes of the Texas and Missouri exurbs. Behind pillared walls of imported granite and marble, a 10,000-seat sanctuary features neither crosses nor organs, but a menorah motif running from entrance to pulpit. Men in shawls and skullcaps that look a lot like Jewish tallits and yalmukahs conduct ceremonies next to Hebrew-inscribed Tablets of Stone and a gilded Ark of the Covenant. The building is meant to be a supersized reproduction of the biblical Temple of Solomon, but by way of Caesar’s Palace.

This is São Paulo, not Vegas or Jerusalem, and the men onstage are Pentecostal pastors, not rabbis. To be more precise, they are Neo-Pentecostal pastors, practicing a syncretic stew of the prosperity gospel, millenarianism, miracle healing, demon invocation, and exorcism, while boasting a level of Judeophilia weird even by the generous standards of Christian Zionism. Once a spiritual outlier, the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (UCKG) stands at the forefront of Brazil’s rapid transformation into a Catholic-minority country. Its seven million members constitute Brazil’s second-largest Protestant denomination, after the Assemblies of God coalition.

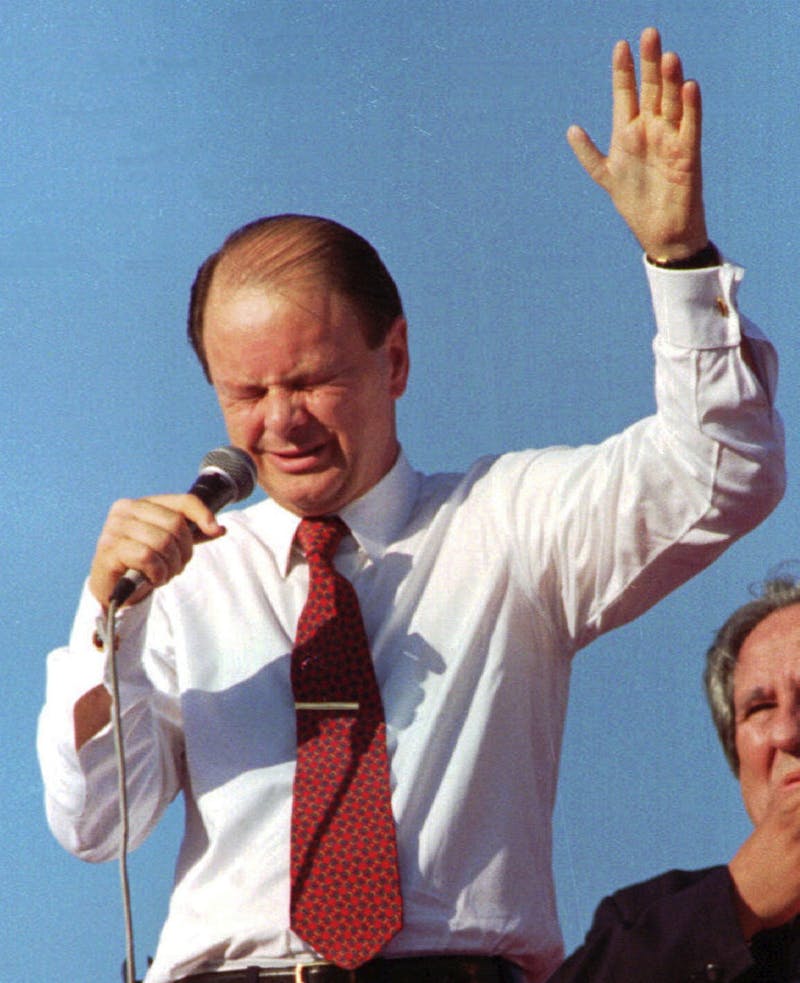

In the UCKG, the Holy Spirit does more than purge demons. It sets believers up for the acquisition of great wealth. The living proof is 74-year-old Edir Macedo, a former street preacher and lottery worker who over the course of four decades has built the UCKG into a billion-dollar church-media juggernaut. This past autumn, he used the levers of this power to help elect Brazil’s first Evangelical president. With the ascension of the far-right ex-Army captain Jair Bolsonaro, Macedo cemented his status as a pivotal figure in the future of post-Catholic Brazil.

“Nobody can rival the electoral discipline of the UCKG,” says Andrew Chesnut, professor of religious studies at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of two books on Brazil’s religious economy. “Macedo was at the vanguard of popularizing exorcism and prosperity theology. Now, he’s arguably the most important Evangelical figure in Latin America.”

Edir Macedo, head of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, leads a service in Rio de Janeiro in 1984. He has since emerged as one of the country’s most powerful political figures.Samuel Martins/JB via AP File

Edir Macedo, head of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, leads a service in Rio de Janeiro in 1984. He has since emerged as one of the country’s most powerful political figures.Samuel Martins/JB via AP FileThe UCKG is the foundation of a global operation that includes a 49-percent stake in a private Brazilian bank, Banco Renner, and a growing media empire, Rede Record, whose properties include Brazil’s number-two television network. In the run-up to October’s election, Macedo used the latter in a powerful demonstration of how Evangelicals are challenging the institutions of a weakened Catholic establishment and Globo, notably Brazil’s dominant media company and TV channel.

“Macedo’s church-media complex does more than proselytize—it expresses and directs the extraordinary growing power of Evangelicals, and especially Neo-Pentecostalism, which is a clear threat to traditional and popular Catholicism,” says Ana Keila Mosca Pinezi, an anthropologist of religion at Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. “The Neo-Pentecostal churches, led by Macedo, have become electoral breeding grounds for conservative candidates. Their power has spread from the peripheries to the heart of politics at every level.”

When Macedo completed his $249 million headquarters in 2014, his point of comparison wasn’t John Hagee’s megachurch or Pat Robertson’s TV studio. It was the Christ the Redeemer statue atop Mount Corcovado, overlooking Rio de Janeiro, the symbol of Catholic dominance since 1921. In interviews, Macedo made sure to note that his Solomonic church was nearly twice as tall.

Jair Bolsonaro’s victory on a far-right platform was powered by historic levels of support from Brazil’s Evangelicals, 40 million and counting, three quarters of whom practice one or another strain of Pentecostalism. As a bloc, they voted three-to-one for Bolsonaro, a portent of a historical shift in the politics of the world’s most religious nation. “For the first time, [Evangelical] voters, who are usually divided, opted as a majority for one candidate,” noted the Brazilian daily Extra.

Macedo’s church is not new to politics. It has always backed and opposed candidates and parties, usually by placing them inside narratives about demons and hellfire. The social-democratic Workers’ Party was a tool of Satan, harboring plans to shut down Evangelical churches—until it became the vehicle for the massively popular President Lula da Silva, and political calculus dictated that it wasn’t so evil after all. Lula fell in a corruption scandal in 2010, and after a hesitant interlude backing his hand-picked but unpopular successor Dilma Rousseff, Macedo turned on the Workers’ Party again, this time for Bolsonaro. He did so with a brazen flexing of his media influence. His TV channel, Record TV, and news website, R7, served as reliable sources of friendly coverage for Bolsonaro, constituting an alternative universe from that found in Globo outlets. (Journalists at both later publicly denounced management for pressuring them to slant coverage, with some resigning in protest.)

Macedo’s media operation is part of a plan for Brazil that, like his ersatz Solomonic Temple, takes its inspiration from the Torah.Record outlets also promoted a rumor, spread widely through WhatsApp, that Workers’ Party candidate Fernando Haddad had developed a “gay kit” to promote homosexuality in schools. On January 8, Macedo’s son-in-law and a leading UCKG bishop, Renato Cardoso, used the Record TV show Intelligence and Faith to denounce the “fake news” attacks of Globo and other broadcasters over the years.

“Macedo uses his cable channel as a kind of Fox News for Bolsonaro and his preferred candidates, providing all positive coverage, all the time,” says Nelson Jobim, a former TV Globo news editor and correspondent for Jornal do Brasil. Jobim notes that Globo has been struggling to keep its audience, and has been forced to moderate its content to appease Evangelical boycotts. Bolsonaro has threatened to cut millions in government ad spending on Globo if it pursues critical coverage, and shift the ad money to Record. “Macedo is building a kind of counter establishment,” he says.

Macedo’s media operation is part of a plan for Brazil that, like his ersatz Solomonic Temple, takes its inspiration from the Torah.

In 2008, Macedo published a book, Plan for Power: God, Christians and Politics, with a heavy focus on Jewish history as a parable for the Evangelicals as God’s Chosen People, a premise that will be familiar to students of the American Evangelical movement. Macedo argues that God has a “dream” to free nations from the godless left and their cultural agenda, just as the Jews were freed and brought to the Promised Land. “God has a great national project developed by Himself and it is our responsibility to put it into practice,” writes Macedo. All that’s required is for Evangelicals to understand their power to implement God’s plan.

The establishment of the State of Israel opened the operational era of God’s plan. Since then, “the sleeping giant” of Evangelical Christianity has awoken, and Brazil is at the heart of the unfolding Biblical drama. “To be an Evangelical in Brazil is like being a foreigner in Egypt at the time of the Pharaohs,” writes Macedo. “Moses’ mission was to liberate the people of Israel, recover their citizenship and guide them to possession of their own kingdom,” he continues. “This book is like the burning bush that revealed God and his great national project to Moses.”

Macedo in action does not possess the power of a Hollywood Moses, or even a cartoon hellfire and snake-handling Pentecostal. He is bald, thin, squinting into the light, a bit shy, with a birth defect resulting in slightly deformed hands. His preaching relies on quantity as much as quality. Hours and hours of it. He talks quietly: “Do you love your wife? Yes or no? Of course you do. Amen.” The sermon drifts, while the congregation nods along. And then you realize that, somehow, he has started talking about the “well-known” danger that Satanists will kidnap your children and sacrifice them. Yes or no? That demons will take you if you don’t pay your tithes. Amen. That he is a poor man and asks only that you give all your money to God. Yes or no? But all in the same soft, reasonable-seeming voice, as if what he is saying is the most obvious thing in the world. If a demon-possessed congregant collapses in front of him, he steps diffidently over him, never missing a beat.

Pentecostalism has always been a religion of the poor, and is especially so in Brazil, where a quarter of the population, 55 million people, live in poverty. The religion arrived in Brazil just a few years after William Joseph Seymour, a one-eyed itinerant preacher from Louisiana, began holding “Baptisms of the Spirit” in the living rooms of Los Angeles’s black working poor. In 1910, two Swedish immigrants to America brought Seymour’s fire to the rubber-boom slums of the Brazilian Amazon. Amid the dense urban squalor of Belem and Manaus, they performed faith healing—cura divina—for indigenous and migrant workers ravaged by the gastrointestinal and infectious diseases rampant in areas without clean water and overrunning with human and animal waste. As the services grew, so did the first Pentecostal churches. They drew so many from the cities’ large leper populations, they were barred from attending.

Pentecostal churches promised health and wealth, in a style that borrowed from, and resonated with, the “demon-filled” religious groups of Afro-Brazilians.“Even if the afflicted eventually succumbed to malaria [or] yellow fever … the therapeutic value of prayer, anointment with oil, and laying on of hands proved real,” writes Andrew Chesnut, the Virginia Commonwealth University professor, in his book, Born Again in Brazil: The Pentecostal Boom and the Pathogens of Poverty.

Poverty has provided the impetus and backdrop for Pentecostalism’s rapid 20th-century growth in Brazil and throughout the Latin world. This was especially true during the late 1970s, when Macedo founded his church in a former funeral parlor in Rio. The 1970s was a decade of rising inflation and deepening poverty in Brazil. By 1980, more than a third of rural citizens were undernourished. Pentecostal churches promised health and wealth, in a style that borrowed from, and resonated with, the “demon-filled” religious groups of Afro-Brazilians, in which Edir Macedo dabbled as a teenager.

“Pentecostalism found a fertile terrain for development in Brazil for two main reasons: society’s syncretic and intensely spiritual and mystical cultural-religious basis, and its economic and social inequalities, slums and social exclusion, ripe for a message of material and spiritual salvation,” says Donizete Rodrigues of the University of Beira Interior.

Between 1970 to 2010, the Evangelical (mostly Pentecostal) population grew from five to 22 percent of Brazil’s population. During an early 90s growth spurt, a galaxy of Pentecostal denominations, small and large, were opening new churches at the rate of one per day. The UCKG was in the forefront, with overflowing coffers that funded expansion into Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, and Colombia, and later to Europe, Africa and, with mixed results, the United States.

Evangelicals in Brasilia pray for the recovery of Jair Bolsonaro, who suffered a knife attack during his presidential campaign.EVARISTO SA/AFP/Getty Images

Evangelicals in Brasilia pray for the recovery of Jair Bolsonaro, who suffered a knife attack during his presidential campaign.EVARISTO SA/AFP/Getty ImagesAna Keila Mosca Pinezi, the anthropologist at Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro, says Pentecostalism feeds into the Brazilian tradition of expecting a messiah figure to rescue the nation, which has origins in myths from the days of Portuguese rule. Lula was the most recent of these figures, and his fall opened a sustained period of scandal and political crisis that allowed Bolsonaro to claim the mantle. The image of the “messiah” was perhaps even stronger during Bolsonaro’s campaign than Lula’s. Having helped destroy the credibility of the opposition, and attained the power to mute and counter criticism from other public figures and institutions, Brazil’s right-wing Pentecostal religious celebrities have emerged as highly influential voices in society.

This influence is built from the money of indigent congregants, who are systematically targeted with warnings about the “godless left.” Macedo’s fortune, possibly the largest of any religious leader in the world, is the fruit of a notoriously aggressive tithing culture. UCKG membership—the majority female, poor, and drawn from the country’s African-descended, indigenous, and mestizo communities—are asked to donate a minimum of 10 percent of their income, plus any extra “sacrifices” they can afford. Tithing can take up one-third of every service, and often resembles a shakedown. “They intimidate people who visit the church,” says Nelson Jobim, a journalist. Pastors may use an open Bible as a kind of fetish, entreating the crowd to cover it with cash, checks, watches, and jewelry. In the São Paulo headquarters, a conveyor belt behind the pulpit carries every holy haul directly past the gilded Ark to a safe room offstage. To stoke the spirit of giving, the voice of Satan himself sometimes rumbles out of congregants’ mouths during exorcisms to describe hell in low, guttural dialogue straight out of a grindhouse horror flick.

Macedo’s love of money is no secret. In 2009, Globo aired a video from 1995 showing Macedo laughing like a low-rent mob boss as he divides up the week’s take with his lieutenants. He has been accused multiple times of corruption and links to organized crime. Carlos Magno de Miranda, who ran the church’s Brazilian operation while Macedo established the UCKG’s U.S. operation in the late 1980s (there are tens of thousands of church members in California), has consistently claimed that Macedo did business with the Cali cocaine cartel in Colombia. He asserts that, in December 1989, he and his wife personally helped transport hundreds of thousands of dollars plus a bag of diamonds from Medellin to Brazil by private jet. This money, he alleges, was used to finance the acquisition of Record TV.

To stoke the spirit of giving, the voice of Satan himself sometimes rumbles out of congregants’ mouths during exorcisms to describe hell in low, guttural dialogue.Macedo laughed off the charges; the Colombian police took them more seriously. After arresting and extraditing a senior cartel member named Victor Patiño to the U.S. in 2002, they discovered the Colombian representative of Macedo’s church, Maria Hernández Ospina, living in one of his properties. (Brazil’s leading news weekly, Veja, reported in 2009 that the Brazilian Organized Crime Unit had been asked to investigate allegations of UCKG money laundering by the Colombian police, but said they had forwarded the dossier to the U.S. authorities because Macedo held a U.S. passport. No prosecution resulted in either country. When contacted by The New Republic in December of last year, an FBI spokesperson neither confirmed nor denied having a file on Macedo, saying only that the agency is obligated to investigate any credible allegation of a violation of federal law.)

Then there is the case of Grigore Avram Valeriu, a Romanian lawyer who headed the church’s legal department in São Paulo. In 1995, he sued Macedo for the return of a family collection of gold jewelry he donated to the church. Valeriu claims church employees melted down the pieces into ingots and smuggled them out of Brazil to one of Macedo’s homes in the United States—a claim backed up by Miranda. Valeriu has set out detailed allegations in books and articles and on TV.

The church no longer bothers to deny the allegations. And if Macedo and his entourage did once traffic illicit jewels, their days of worrying about airport bag searches are long gone. Since 2006, Macedo has traveled by private jet on a Brazilian diplomatic passport, a privilege previously granted only to senior Catholic clergy.

Having seemingly established de facto legal impunity, Macedo glories in the repetition of old charges and the launching of new press attacks, using them as further proof of Satan’s desperate campaign to defeat him. Despite many attempts at prosecution, he was only jailed once, in 1992, for 11 days. A photo of him sitting in a jail cell holding his Bible is one of his most valuable advertising images. A self-produced 2018 Macedo biopic called Nothing To Lose was the most successful Brazilian film ever, beaten only in absolute ticket sales by Avengers: Infinity War. The poster is a glamorized version of the jail photo. Left-wing journalists point out that the movie played to empty theaters in which Macedo’s organization bought all the tickets and didn’t even bother to give them away.

The Catholic Church has made adjustments in an

attempt to stop the bleeding of converts to Pentecostalism. The Church’s so-called “charismatic renewal

movement” has borrowed some of the entertainment trappings of Pentecostal

services, with the Canção Nova, or New

Song movement, targeting youth with stadium shows and radio programs. But this

has also moved the Catholic Church in the direction of a fundamentalism and conservative

politics that increasingly plays into the hands of the Evangelicals.

The temple of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God in São Paulo. Macedo has noted that it is twice as tall as Rio’s iconic Christ the Redeemer statue.Miguel Schincariol/AFP/Getty Images

The temple of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God in São Paulo. Macedo has noted that it is twice as tall as Rio’s iconic Christ the Redeemer statue.Miguel Schincariol/AFP/Getty Images“Pentecostalism has been so successful in Brazil, especially since the 1970s, that in order to compete, both the Catholic Church and other Protestant denominations have had to Pentecostalize, offering spirit-filled worship that is very similar to that found in Pentecostal churches,” says Chesnut. A recent Pew survey found that about half of Brazilian Catholics now identify as charismatics, practicing a Catholicism that can look and sound a lot like Pentecostalism with a Pope.

The Church hierarchy, meanwhile, has taken a more conciliatory approach to its brashest challenger. In the past, Catholic bishops and archbishops denounced Macedo’s operation as criminal and blasphemous, with its blessed envelopes for donations and bottles of magic oil from Israel. But in 2016, the Archbishop of Rio, Cardinal Orani Tempesta, openly supported the successful candidacy of Macedo’s nephew and UCKG bishop, Marcelo Crivella, for mayor of Rio. (When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited a group of Brazilian Evangelicals in Rio last December, it was Crivella who welcomed him and hosted the ceremony.)

Politically, the Bolsonaro government provides a window into what Mauro Lopes, editor of Brazil 247 and a leading liberal journalist, sees as a convergence between right-wing Catholic fundamentalists and the Evangelicals. “The Catholics of the extreme right supported Bolsonaro in the elections and now they are receiving him as one of their own,” he says. “[This alliance] is getting clearer every day.”

This Catholic-Evangelical alliance reflects Bolsonaro’s own identity. Although now officially Born Again, he has not renounced his Catholicism. The make-up of the new government is similarly divided: Bolsonaro’s minister for women, family and human rights, Damares Alvez, is an Evangelical pastor; his foreign minister, Ernesto Araujo, is a right-wing Catholic intellectual who quotes Wittgenstein and gives his Biblical quotations in Greek.

Bolsonaro’s “guru” on the moral turpitude of the left is a Virginia-based philosopher, Olavo de Carvalho, who argues that the left in Brazil is controlled by a corrupt elite that has abandoned its Marxist roots in favor of a “cultural Marxism” that promotes gay marriage and feminism. Carvalho also seems to believe that TV forms the intellectual and emotional lives of Brazilians, claiming that the 30 people at the top of Globo control the entire country.

How this arrangement of forces evolves, at least in the short term, depends on the performance of Bolsonaro’s government on behalf of a newly unified Evangelical vote. A nationwide poll from Datafolha from mid-January shows large majorities, up to 70 percent of respondents, disagree with his actual policies. His promise to provide security was immediately challenged by an armed insurgency from drug gangs across Ceará state, to which his government had no new response. “They will not be able to solve the serious problem of violence,” says Donizete Rodrigues, who studies Brazilian politics at the University of Beira Interior in Portugal. “Bolsonaro represents the military class, which has already shown itself unable to contain the violence in Rio de Janeiro.”

Corruption scandals, meanwhile, have already begun swirling around Bolsonaro and his family, leading to a sense of business as usual. God seems to have sent some fresh challenges, too: The collapse of the Brumadinho dam in January is an epic catastrophe. The surgery that saved Bolsonaro’s life after he was stabbed during his election campaign—surgery he has described as a “miracle,” and a sign that he was chosen by God—has led to complications that have put him back in hospital.

Macedo, for his part, has been quiet since the election. Rodrigues suspects he has more pressing concerns than the vicissitudes of national politics. “My guess is he’s more interested in the development of Brazil CNN, a possible competitor, whose incoming CEO, Douglas Tavolaro, is a former longtime Record executive,” says Rodrigues. Whatever happens with Bolsonaro or the new cable network, Macedo is surely looking ahead. If he understands anything, it is the many forms of power and what they can accomplish, in concert, not over years but decades.

No comments :

Post a Comment