President Donald Trump makes no secret of his disrespect for the other two branches of government. He has taken to describing routine congressional oversight of his administration as “presidential harassment” and often harangues federal judges who rule against him in legal proceedings. Matt Whitaker, Trump’s hand-picked acting attorney general, seems to share that disdain for the separation of powers.

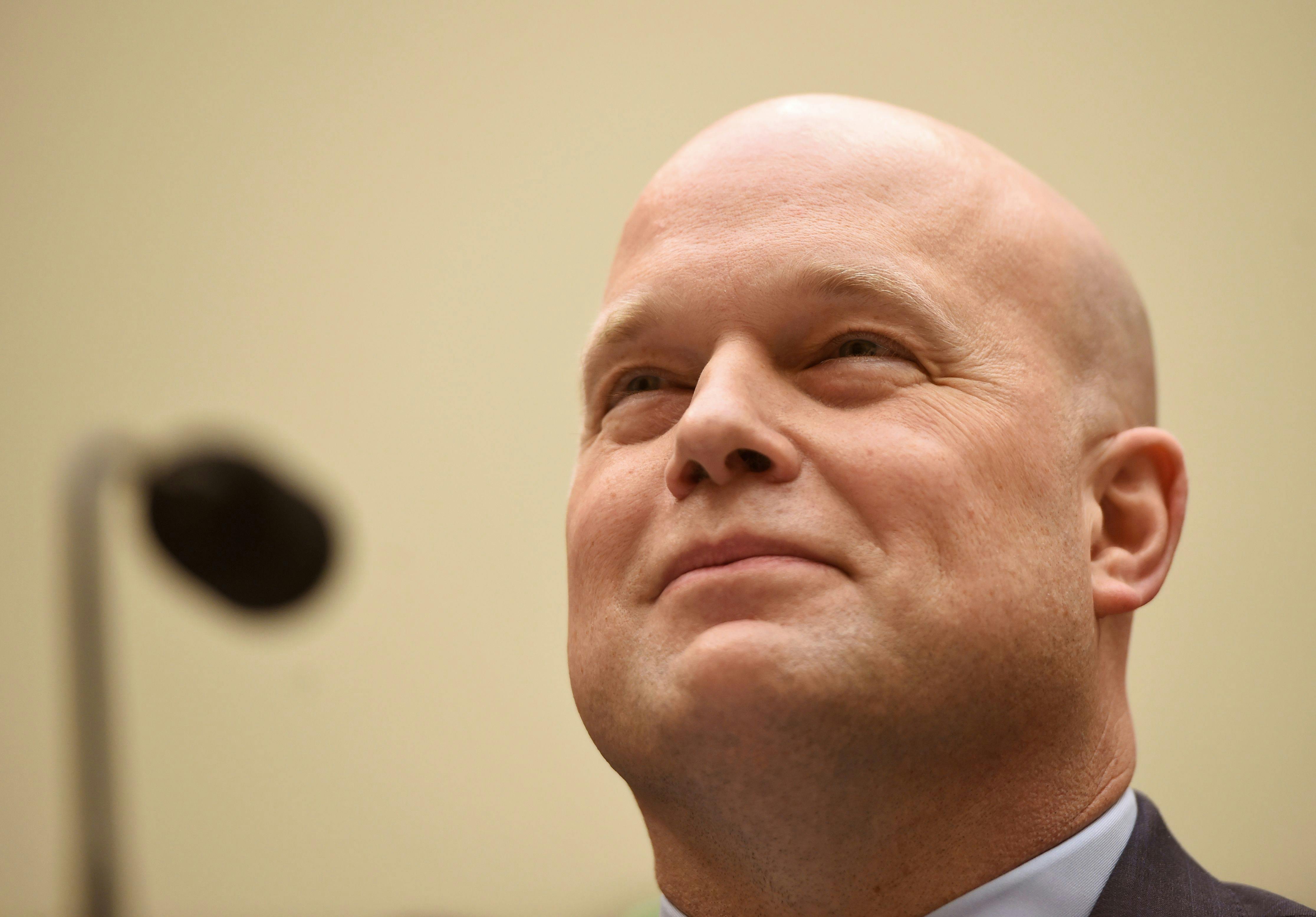

In a contentious appearance before the House Judiciary Committee on Friday, Whitaker frequently adopted a recalcitrant tone toward lawmakers. He seemed allergic to giving a straight answer. Simple yes-and-no questions received laborious and long-winded responses, even when he was quizzed by Republican lawmakers who are sympathetic to the president. To deflect questions about his personal views and professional history, Whitaker repeatedly noted that the hearing wasn’t supposed to be a Senate confirmation hearing. He may be lucky that it wasn’t, since his performance seemed to win him few friends on the committee.

At times, Whitaker’s obstinacy veered into outright hostility. “Have you ever been asked to approve any request or action to be taken by the special counsel?” Jerry Nadler, the committee’s chairman, asked as his allotted time for questions ran out. The acting attorney general didn’t answer the question. “Mr. Chairman, I see that your five minutes are up,” he replied, to loud gasps in the hearing room. When he made another quip about the members’ time limits later in the hearing, Representative Sheila Jackson Lee chastised him. “Mr. Attorney General, we’re not joking here,” she said. “And your humor is not acceptable.”

The hearing foreshadowed what congressional Democrats will likely face as they gear up for a cavalcade of oversight inquiries into the Trump administration. Whitaker appeared before the committee only after clashing with Nadler over the possibility that he would be subpoenaed mid-hearing and compelled to answer questions, a threat that Nadler ultimately dropped. He evaded some questions by raising the specter of executive privilege, which the president can invoke to shield some communications with subordinates from legislative and judicial scrutiny. Most Republicans, meanwhile, used the opportunity to criticize the Democrats’ inquiries as a purely partisan charade.

Few of the Democrats’ targets for congressional oversight rank higher than Whitaker. Trump ousted Jeff Sessions as attorney general in November and tapped Whitaker, Sessions’s chief of staff, to serve in an acting capacity. Whitaker’s past criticism of the Russia investigation raised serious concerns that he would use his temporary position to bend the Justice Department to the president’s whims. Next week, the Senate will likely confirm Bill Barr to serve as the next attorney general, giving Democrats only a brief window to question Whitaker while he serves in the post.

In Friday’s hearing, Whitaker offered only a half-hearted defense of the Justice Department’s traditional independence. “At no time has the White House asked for, nor have I provided, any promises or commitments concerning the Special Counsel’s investigation, or any other investigation,” he asserted in his opening statement. But he also declined to defend the Russia investigation’s legitimacy as Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and FBI Director Chris Wray have publicly done. “Are you overseeing a witch hunt?” asked Representative Steve Cohen. “It would be inappropriate for me to talk about an ongoing investigation,” Whitaker replied. Like many of the president’s other subordinates, his performance appeared tailored to an audience of one.

Whitaker gave the committee some assurances under oath about his handling of the inquiry. “I have not talked to the president about the special counsel’s investigation,” he told lawmakers who expressed concern about whether he gave inside information to the White House. He also said that while he had been briefed on the investigation’s actions, he had not changed its course. “There has been no event or decision that has required me to take any action, and I have not interfered in any way with the special counsel’s investigation,” Whitaker testified. Under the Justice Department’s regulations, the attorney general is required to notify Congress if he or she countermands a special counsel.

Other responses raised more questions than answers. Whitaker demurred when Val Demings, a Florida Democrat, asked whether he had discussed the federal investigation in the Southern District of New York. “I am not going to discuss my private conversations with the president of the United States,” he told her. He also admitted that he had only interviewed for two jobs in the Trump administration: to be Trump’s in-house attorney for responding to the Russia investigation, and the chief of staff position under Sessions. At the end of the hearing, Nadler said Whitaker’s testimony was “not credible” and that he might call him back before the committee to give a closed-door deposition.

“This administration is used to evading any questions they want to evade. They’re used to not having to answer the questions,” he told CNN’s Manu Raju. “We’re going to pursue them we’re going to show them that era is over and that the questions.”

House Republicans, for their part, used Friday’s hearing to cast both Democratic oversight efforts and the Russia investigation as partisan and illegitimate. “This is nothing more than character assassination,” Doug Collins, the committee’s ranking GOP member, said. He raised points of order throughout the hearing to interrupt Democrats who asked questions that he found impertinent. The most pointed outburst came when Eric Swalwell, a California Democrat, asked about donors to a nonprofit that Whitaker once worked for. “If you would ask questions that are actually part of this instead of running for president down there, we could get this done,” Collins said, referring to Swalwell’s rumored aspirations.

Most of Collins’s own questions for Whitaker focused on the spurious allegation by Trump and his allies that the Justice Department tipped off CNN about Roger Stone’s arrest. Whitaker said he was concerned about the possibility, but had no information to suggest it had happened. Jim Jordan, one of Trump’s closest allies on Capitol Hill, grilled Whitaker on Rosenstein’s partially classified memo laying out the scope of Mueller’s inquiry. His questions tried to suggest, without offering any proof, that Rosenstein had directed Mueller to investigate specific people instead of potential crimes. Some Republican lawmakers used their time to ask about violent crime or the opioid epidemic. But most of them focused on the president’s political fortunes, and the danger that federal and congressional inquiries could pose to them.

That danger will likely be forefront on lawmakers’ minds as other Trump administration officials come before congressional committees over the next two years. Steven Mnuchin, the secretary of the Treasury, is negotiating with House Democrats about when he’ll testify about Russian sanctions. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross is slated to appear before the House Oversight Committee in March to answer questions about the 2020 census, a controversial proposal to add a citizenship question to it, and whether he lied to Congress about his involvement in that decision. The House Homeland Security Committee is also sparring with Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen about her potential appearance there.

Whitaker’s rocky appearance underscores the peril that Trump officials will face when they’re brought before Congress. The fight to get him there also shows that they aren’t completely at the mercy of House Democrats. Aggressive invocations of executive privilege and hardball negotiations could gum up the works and slow down the Democrats’ momentum, especially if GOP lawmakers lend the administration a hand. If nothing else, the Whitaker exit interview suggests they’ll be pulling out all the stops to protect the president.

The Iowa caucuses are still more than a year away. The first Democratic primary debate won’t occur until this June. But some journalists are already declaring that one of the party’s 2020 frontrunners, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, is in serious trouble.

After it was revealed recently that Warren had listed her race as “American Indian” on a State Bar of Texas registration card 33 years ago, The Washington Post commented that the “matter now threatens to overshadow the image Warren has sought to foster of a truth-telling consumer advocate who would campaign for the White House as a champion for the working class. Instead, she is now seeking to combat the portrait of someone who for years was insufficiently sensitive to a long-oppressed minority.” The New York Times’s Peter Baker seemed to concur on Twitter, and MSNBC’s Brian Williams devoted nearly ten minutes of his show to the controversy, declaring that it “follows and looms over her candidacy.”

Warren’s handling of the controversy—particularly her decision to take a DNA test to prove distant Native American ancestry—has been seriously flawed, and is worthy of coverage. But that’s not what’s looming over her presidential campaign. Instead, many in the media are giving the same credence to Republican attacks that they did in 2016, when Hillary Clinton faced “lock her up” chants for her use of a private email server, and 2008, when Barack Obama was forced time and again to prove he was born in Hawaii, not Kenya. (It is no coincidence that Donald Trump has been the leading instigator in all three cases.)

Questions about Warren’s Native American heritage—and whether or not she used those claims to advance her career—have dogged her since 2012. That year, Republican investigators found stories in the Harvard Crimson touting diversity among Harvard Law School faculty that referred to Warren as a Native American. Her ethnicity was also listed as “Native American” at the University of Pennsylvania, where Warren taught before joining Harvard. Trump has ridiculed her for years by referring to her as “Pocahontas.”

Conservatives have obsessed over Warren’s Native American claim because it allows them to attack two foes at once. They’re using it not only to discredit Warren herself—an accomplished intellectual with an impressive academic and political career—but also the very legitimacy of affirmative action. The idea is that Warren only got ahead in the professional world by fraudulently taking advantage of a liberal policy.

“Why would Warren pretend to be an American Indian in the 1980s if later she downplayed the matter as a misunderstanding based on family lore?” James J. Robbins wrote in USA Today on Thursday. “Fairly obviously it was for career advancement. Despite the current leftist mania to call out supposed ‘white privilege,’ the fact is that even in the 1980s minority status could confer distinct advantages in hiring and promotion in career fields dominated by liberals for whom affirmative action is an article of faith.”

And yet, there’s no evidence that Warren claimed minority status for preferential treatment. She has been remarkably consistent about her background. While she never belonged to any of the three federally recognized Cherokee tribes, she has always described her mother as “part Cherokee” and said she learned of this heritage through her family’s oral tradition. The most recent iteration of the scandal, involving Warren’s Texas bar card, supports this. The information on that card was private; Warren would not gain any advantage from listing herself as Native American. Even the aforementioned Post story eventually gets around to that truth, albeit not until the eighteenth paragraph:

There’s no indication that Warren gained professionally by reporting herself as Native American on the card. Above the lines for race, national origin and handicap status, the card says, “The following information is for statistical purposes only and will not be disclosed to any person or organization without the express written consent of the attorney.”

There is a scandal here, it’s just not the one the right—and, too often, the mainstream media—is talking about. In October, Warren released the results of a DNA test that showed “strong evidence,” a geneticist said, of Native American ancestry “6-10 generations ago.” She was rightly criticized for doing so. As The New York Times’s Astead Herndon reported two months later, the move “troubled advocates of racial equality and justice, who say her attempt to document ethnicity with a DNA test gave validity to the idea that race is determined by blood—a bedrock principle for white supremacists and others who believe in racial hierarchies.”

Warren, to her credit, has apologized for the DNA test. But the story continues to roll on. Despite admitting several times that Warren never received any advantages from identifying as Native American—the core of the right’s argument against her—CNN nevertheless declared that “Elizabeth Warren’s Native Problem just got even worse” after the Texas bar story dropped. But that revelation didn’t change what we already knew. All it did was give the media yet another reason to assert that her Native American claim is haunting her presidential campaign.

This is precisely why the right has latched onto this story, knowing full well that the mainstream media feels compelled to cover any sustained political frenzy, no matter how disproportionate or phony the allegations may be. The Native American claim is the perfect vehicle for conservatives to undermine a female Ivory Tower academic who is a persistent and effective critic of crony capitalism, and to expose affirmative action as a liberal plot to discriminate against white men and eliminate meritocracy in America. These attacks, particularly Trump’s vile “Pocahontas” label, seek to mark Warren as an outsider—a line that is not dissimilar to the “birther” smear against Obama that became the foundation of Trump’s political career.

That this “scandal” overshadows Warren’s policy ideas—such as her recent “wealth tax” proposal—is exactly the point. Instead, breathless coverage is given to every twist and turn of this saga: It’s become a self-sustaining cycle, the culmination of years of pathological dedication from the right. That’s troubling, especially given the stakes in 2020. During the last presidential election, the media gave similarly breathless coverage to every twist and turn of the Clinton email saga, and seemed unable to discern the meaningful aspects of that story from the irrelevant details. It may well have cost her the election. Warren, and Democrats broadly, have reason to fear a repeat of that fate.

Kamaltürk Yalqun’s father was sentenced to 15 years in a Chinese prison early last year. As a prominent Uighur scholar and writer, he was among the first to be swept up in October 2016 as China embarked on its largest detention campaign since the Cultural Revolution. “Whether you become an activist or not, it doesn’t matter. If you are a Uighur, you will be a target,” Yalqun said.

On Tuesday, Yalqun was among nearly 200 protesters rallying outside the United Nation headquarters in Manhattan to plead for greater international attention to China’s accelerating detention of Uighur and other Muslim minorities in its northwestern region of Xinjiang. One told me Chinese agents called him three weeks ago to warn against drawing attention to the detention of his parents and brother, a popular singer—neither had a past history of activism, he said. Another recounted the detention of her aunt and sister—also without a history of political involvement, she said. All of these protesters had decided to risk harassment from a rising superpower determined to thwart any criticism of its sweeping campaign.

These detained relatives are now part of a sobering figure: The U.S. State Department estimates that between 800,000 and two million people are being held indefinitely in a sprawling network of more than 1,000 Chinese internment camps. Up until October last year, the Chinese government denied their existence. Now, they say they are “vocational training centers” meant to curb extremism. But human rights organizations say the camps are being used to sever Uighurs’ ties to Islam.

The protest aimed to generate support for the Uighur Human Rights Policy Act, a bipartisan bill reintroduced in Congress last month that would sanction Chinese officials and companies involved with the internment camps. It comes amidst tougher attitudes toward Beijing, particularly from the Trump White House, on issues like trade, national security and technology.

The international community’s response to mass detention in China has been “anemic” so far, Sophie Richardson, the China Director of Human Rights Watch told me. Western diplomats and U.N. human rights officials have denounced China’s actions in Xinjiang, and Vice President Mike Pence is the most senior Trump administration figure to condemn it. But as of yet, the administration’s intense focus on tariffs to punish Chinese trade malfeasance has not included threats of targeted sanctions to punish human rights violations. “What does it say when a permanent member of the UN Security Council can do this in view of the whole world?” Richardson said, referring to China’s mass detention program. “We can’t say we didn’t know.”

But not only has the U.S. known about China’s Uighur detentions—at crucial points, it has in fact bolstered Beijing’s case for the persecution.

The modern Chinese state has long treated the Turkic-speaking Uighurs with anxiety and unease over their distinct culture and Islamic identity forged over centuries. Xinjiang—almost the size of Alaska—is China’s largest region, a land of vast deserts once so inhospitable that it is believed to have been among the last places on earth to be settled, requiring irrigation techniques for habitability. After Mao Zedong seized power in 1949, the Chinese government encouraged the migration of ethnic Han to the territory to fend off independence efforts in the region. Tensions simmered for decades as the government sought to mold Uighurs into loyal supporters of the Communist Party. The government pushed policies to spread the Mandarin language and Chinese culture, and imposed restrictions on how Uighurs could express their faith. Today, 11 million mostly Muslim Uighurs—nearly half of Xinjiang’s population—call it their homeland.

The U.S. designation of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement as a terror organization after the 9/11 attacks represented an “inflection point.”The crisis in Xinjiang is worsening under Xi Jinping, the nation’s most powerful ruler since Mao, and who continues expanding the Communist Party’s influence in Chinese society after six years in power. “The party sees Islam as a threat to their continued rule over China,” said Dr. Rian Thum, a researcher focusing on Uighur society at the University of Nottingham.

But the Chinese government’s policies, Thum adds, have also been intensified by Western Islamophobia—meaning that inaction in the present isn’t the only way the United States has contributed to Uighur persecution. Thum says the U.S. designation of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement as a terror organization after the 9/11 attacks represented an “inflection point” that realigned the Chinese government’s approach towards Xinjiang. Beijing subsequently portrayed any protest as a sign of disloyalty and desire for independence, and more frequently alleged separatist coordination with Islamist groups beyond its borders, leading to heavy-handed security crackdowns when unrest broke out. In 2009, mass protests that left almost 200 people dead in the capital of Urumqi prompted the government to cut off internet, phone, and text messaging services for a year in the region. Though few Uighurs turned to religious militancy, the government connected its security policies to the U.S.-led “war on terror,” thanks partly to the precedent set by the United States’ extended Guantanamo Bay detention of 22 Uighurs captured in Afghanistan in 2001—now widely seen as a mistake. In 2004, Amnesty International claimed to have evidence the U.S. had even hosted a Chinese interrogation of the detainees in 2002.

The

appointment of Chen Quanguo as Xinjiang’s party secretary in 2016 heralded

further repression. Chen had previously implemented a

system of grid policing to quell riots in Tibet. In Xinjiang, Chen created an

Orwellian surveillance network that undergirds the current detention campaign,

tracking residents wherever they go. Facial-recognition cameras maintain tabs

on individuals, DNA samples are mandatory and fingerprints are collected for

government databases. But the extreme surveillance pales against what detainees

experience in the camps: Former camp inmates have testified

that they have been subjected to torture, starvation and other cruelties.

The broader Islamic world has been conspicuously quiet about this persecution of a Muslim minority. The Organization of Islamic Cooperation said nothing during a November review of China’s human rights record at the UN. Few leaders have spoken up. Many risk looking like hypocrites over their own records of human rights abuses if they confront China—or risk imperiling lucrative partnerships. China has invested heavily in development projects in recent years, most prominently through its Belt and Road Initiative, a massive construction project designed to connect Africa, Europe, and Asia through transportation networks. Turkish journalist Mustafa Akyol, writing in The New York Times in January, argued that deepening economic relationships, coziness with authoritarianism and the allure of a “Confucian-Islamic” alliance against the West outweigh the political willingness of Muslim governments to act.

As the Chinese government continues detaining Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, the lack of meaningful action could put other religious minorities at risk as well. CNN reported last month that the Chinese government shut down dozens of Protestant Christian churches in 2018. Arrests seem to be increasing as well. Concern is growing that the Chinese government will feel emboldened for further religious crackdowns, or to use methods perfected in Xinjiang to quell unrest in restive regions like Tibet. Thum says “it’s very likely” that the harsh tactics in Xinjiang can be used elsewhere, noting they’ve been applied against Tibetans and Falun Gong members. “Whether that happens depends on the reaction of the outside world,” he said. A day before the protest, human rights organizations called for a new UN investigation of China’s detention of Muslims, to maintain what little international pressure currently exists.

President Trump has drawn attention for praising strongmen and dictators, relatively unconcerned by their human rights abuses. Supported at home by white evangelicals, however, the administration has shown interest in the foreign troubles of Christians, specifically—both attempting to exempt Middle East Christians from a crackdown on predominantly Muslim countries, and working to secure the release of pastor Andrew Brunson from Turkish detention last fall. If the Chinese government does turn its eye from Xinjiang to the country’s Christians, U.S. attention to the situation would likely increase. The advanced surveillance and detention system Beijing would turn to the task, however, would be the one perfected on a minority the United States has repeatedly declined to protect.

No comments :

Post a Comment